The Southern-Belgian former industrial stronghold of Charleroi is dealing with a rather differing reputation. Some people associate the city with either industrial decline, political corruption, notorious serial killers or terrorist hide-outs and therefore with its infamous image as Europe’s ugliest or most-depressing city. Even by Belgians, Charleroi is often thought of as a black spot on the national map nobody wants to associate with, except for catching a cheap Ryan-Air flight from the local airport. At the same time however, the Pays Noir is beloved by urban explorers as being a paradisiacal playground for making amazing photographs. Suchlike urban creatives often stress the ‘edgy appeal’ of the city by highlighting its supposedly raw and creative cultural scene with a lot happening outside the mainstream. Some even herald the city’s revival by labelling it the ‘new Berlin’ (a catchphrase popping up every now and then).

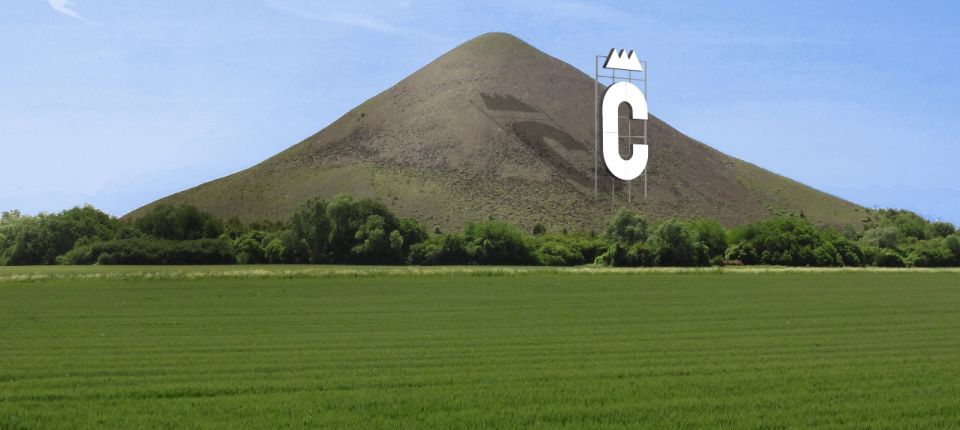

Whatever one’s prejudice on Wallonia’s largest agglomeration may be, urban creatives increasingly seem to find their way to the city. Both public and private investors look for opportunities as “a breath of fresh air” is allegedly present. Last year, the city was granted a large amount of FEDER funds, European support for regional development, to revitalize its downtown and Northwestern quarters. A Charleroi District Créatif (DC) will be realized, that needs to supply Charleroi the metropolitan functions it currently misses, such as a university campus, conference center and a shopping complex. The new city symbol (see banner) illustrates this reimagining of the city’s identity, as the nature of the letter, a hemisphere open in the middle, “evokes the contours of a city open to the future and to the world”.

Is this combination of bottom-up and top-down interventions enough to overcome the city’s post-industrial struggles, as some other authors have carefully suggested? Are things really starting to change socially and economically? We tried to find out ourselves by exploring the city with the help of local tour guide Nicolas.

View on one of the numerous factories along the Sambre

Commerce à louer

Local art graduate Nicolas Buissart is the driving force behind the City Safari Charleroi: an epic and rather ironically conceived tour that will “reveal to you the unknown mysteries of the most interesting post-industrial region in Europe”. While the concept has angered municipal authorities, the safari now attracts visitors from across Europe. In a small group, mainly consisting of Belgian and Dutch youngsters, we embarked on our peculiar type of expedition.

We first halted near the heart of the historic center, which is currently one large construction site. If all goes as planned, Les Carolos will be able to visit their new ‘Rive Gauche’ shopping complex by the end of this year. As academic literature demonstrates, the planning of suchlike sites of leisure consumption is a very common policy response to urban decline. The project’s name reveals that inspiration has been taken from the Parisian left bank of the Seine river, an area known for its many early 20th century intellectuals and cosmopolites. On the developing agent’s website, the usual, often exaggerating marketing-slogans are preached; e.g. the project is deemed to “revolutionize Charleroi” and to create “a buzzing urban quarter” by hosting luxury shops and boutiques, art and film exhibitions and quality restaurants and bars. Whether a critical mass of consumers with a ditto purchasing power is present or can be generated, remains however to be seen. After all, walking through some of the adjacent shopping streets such as the Rue de la Montagne, the commerce à louer signs appear with an average pace of five windows (see pictures below). This whilst, according to Nicolas, rent prices are already “cheaper than the cheapest place in Brussels”. We therefore question whether a luxury downtown shopping will successfully take off in the near future given the apparent degradation of the downtown retail and housing market.

- Empty shops are plentifold in Charleroi’s city centre

Battle for the functions

After our walk through the ville basse, we left the city centre by secretively climbing over the concrete walls of the enormous and fully empty Charleroi Expo parking, thereby carefully avoiding junkie leftover materials. This expo site will be entirely renovated and is one of the main projects of the Charleroi DC masterplan. Along with the adjacent Palais des Beaux-Arts (soon to be renovated as well) and the newly planned conference center, these sites will be architecturally interconnected and are therefore deemed to function as one “united pole of international conferences and events” in the near future. After crossing the railway tracks next to the Expo, Nicolas informed us that at this part of town as well, some large-scale development projects are on their way. At the site of the old tire factory for instance (see picture below), a new Decathlon branch will be realized. According to Nicolas, the planning of suchlike metropolitan functions is part of the city’s continuing strategy to compete with the other regional cities in the vicinity like Mons, Namur and Liège. “A battle for the functions”, he labelled it. A similar sense of rivalry has been evoked when, in 2007, Google selected a small village just outside of Mons as the location for its new European datacenter, thereby investing some €450 million. Simultaneously, other tech-firms such as Microsoft co-located at the site, rapidly creating a so-called mini Silicon Valley near Mons: the ‘Digital Innovation Valley’ (a catchy label clearly launched as part of the ‘Mons 2015 cultural capital of Europe’ campaign). This digital innovation hub has allegedly created economic and commercial growth for the city of Mons. Whether Charleroi will be able to benefit from high-tech developments in the region (looking at the vicinity of university-town Louvain-la-Neuve?), is currently hard to predict.

Abandoned tire factory.

Fifth-generation factory workers

Next, Nicolas’ city safari returned to the city centre where it led us along rather low-end bars with television screens broadcasting the news, gambling machines being eternally occupied by elderly men bearing the traces of generations of factory labour, peculiar objects like leprechauns and a menu that only offers a few pretention-less snacks such as sandwiches with ‘preparé’ (better known as filet americain in Holland). Thus, contrary to what has been suggested elsewhere, no hip coffee or hamburger bars to be found here yet, nor any other apparent signs of gentrification or ‘bottom-up creativity’. While all this may at least be called ‘authentic’, our guess is that even the ‘proper hipster’ will feel unheimlich being dependent on the city’s current facilities. Even a nice specialty-beer café, usually omnipresent in Belgian cities, is quite difficult to find in Charleroi. With lack of more pleasing alternatives (or just being badly prepared), we had to eventually content ourselves with the highly commercial and cheerless ‘Leffe-café’.

City centre café’s.

After the tour, we attempted to get a taste of Charleroi’s nightlife. After trying out quite a few places, we bumped into ‘Rockerill’: a forge that has been reconverted into a concert hall, exposition room and artist ateliers. Beautiful artworks made of industrial leftovers were showcased. However, besides this venue, our recurrent observation was the abundancy of middle-aged mixed crowd, either listening to loud rock music from the Fordist-industrial era, or intimately dancing on tacky nineties-music. It therefore did not take us long to carefully predict that Charleroi’s social and cultural dynamic will not likely soon resemble either a Parisian grandeur or a Berlinesque hipster-scene. However, perhaps this is currently not the main issue the city’s policy makers should be worried about. Hipster economics hardly ever prove to be a real game-changer for the entire population. This is also the reason why ‘hipster-initiatives’ in (for instance) the struggling post-industrial city of Detroit often face fierce skepticism.

Anticipating the future: “Charleroi Métropole”?

Although many urban and economic geographers have extensively analyzed the ‘success-factors’ of post-industrial policies, a straightforward off-the-shelf solution does not seem to exist. Charleroi Bouwmeester and the city government claim to be aware of this, and state in their recent report “Charleroi Métropole: un schema stratégique 2015-2025” that “inspiration is not the same as imitation”. They hereby refer to a number of successful cases of post-industrial revival such as Brooklyn, Nantes and Bilbao. Endowed with the necessary ambition, the powers that be are instead imagining Charleroi’s own “particular transformation process” towards a new urban economy by providing it with new metropolitan functions. Together with a clear focus on consumption and culture, a reviving ‘metropolitan’ identity is thus strongly aspired.

Whilst successful transitions of post-industrial cities through cultural tourism development have been observed before in e.g. Manchester and Liverpool, re-imagining a city’s ‘identity’ will – in the case of Charleroi – not be enough. To save this struggling city, the struggling part of the city population needs to be taken into account as well. After all, downtown redevelopment and a new, more appealing image are necessary but far from sufficient to create a healthy and revitalized Charleroi.

All in all, as some other scholars have stressed, the key to post-industrial successes have mostly been individual actors and/ or political structures. Charleroi therefore needs to hold on to a consistent long-term policy that is characterized by robust and cooperative governance arrangements, also taking into account the needs of the more disadvantaged part of the local population. It should also be noted here that, throughout history, Charleroi has not distinguished itself as Belgian’s most ethical city in terms of politics. After all, frequently recurring corruption scandals continue to hamper efficient governance.

We are therefore curious to see whether a solid mixture of top-down and bottom-up initiatives will turn out to be successful for the socio-economic future of Charleroi. On the basis of our current impressions, there is still quite a long way to go. For all the Proto City-readers who also visited this peculiar part of Belgium, feel free to join the conversation and share your (different?) experiences and observations here with us!

All pictures are taken by the authors.

- Art made of old industrial leftovers in ‘The Rockerill’.

- Walking along a graffiti-wall during the tour.

- Abandoned forge

- Industrial heritage

- Abandoned water tower.

- Entrance of the city’s subway..

- View on the city from ‘Terril’.

- Downtown shopping mall development

- Street art