There is no city that has undergone such a tumultuous development history as Detroit. Once being the fastest growing city and music capital (Motown records) of the United States, the city was a dream for capitalist entrepreneurs and top-down city planners. Fueled by the thriving auto-industry, Detroit’s population grew to almost 1,9 million inhabitants in the 1950s. The sky was the limit and policy makers and planners even started to lay-out a plan for three million inhabitants. But the rapid era of growth suddenly stopped, and Detroit’s golden days were over much sooner than expected. Due to global economic restructuring, the auto industries left for cheap labor destinations. And along with the manufacturing industry, Detroit’s’ population fled the city in distress, leaving Detroit with high unemployment, little services and a financially drained municipality behind. Over the last decades, the city has seen its population cut in half and has been called the biggest Urban Failure in the United States. To turn the tide, multiple public, private, and grass-roots efforts are undertaken to get the city back on its feet. However, looking at a devastated Detroit, is there still any potential for a comeback? And if so, how effective are the efforts currently undertaken? Curious about these dynamics, we hopped on a bicycle to find out what might cause the Motor City to boogie back.

The Detroit Train-station: Once the highest station in the U.S, now left abandoned (Photo: authors)

Abandoned Midtown in contrast to Detroit’s downtown (photo: authors)

Top-down planning Attempts

In 1977, General Motors decided to locate its headquarters to Detroit’s downtown waterfront in an effort to revitalize Detroit, which has witnessed a loss of jobs and population since the 1950s. The office complex is named ‘Renaissance Center’, as it gave downtown Detroit a critical mass of 15.000 employees and a new architectural icon. Although some other companies followed GM back to Detroit, the intervention seemed insufficient to revitalize the whole downtown area on its own, as the city continued to lose population.

Ten years later, a federal grant for local transport innovation was rewarded to Detroit. The city – already in deep financial problems as a result of decreasing tax revenues – welcomed any federal funds it could lay its hands on, and proposed to build a futuristic monorail system. The so-called ‘people mover’ was designed as a regional transportation system, but due to budget constraints and construction issues, the system now only encompasses the downtown area (+/- 3 kilometers). The system offers a great ride for tourists, but does little to improve the accessibility of Detroit. The latter remains to be a major concern for Detroit, as its public transportation system is one of the most deprived systems in the US, resulting in a disintegrated urban region of an active downtown, abandoned spaces and wealthy suburbs.

The Renaissance center (Photo: authors).

More recently, two huge sport stadiums have been built. The American Football Stadium ‘Ford Field’ (2002) has a maximum capacity of 80.000; the new baseball stadium for the Detroit Tigers (2000) has over 41.000 seats; in 2017 the new Red Wings Ice hockey stadium, supported by up to 450 million dollars of state bonds, is scheduled to open. While these sport facilities contribute to a new, more positive image of Detroit, it can be questioned whether it will improve the current disintegration between the city and its hinterland, as the suburbanites only occasionally drive to the city for a sports game.

Large scale investments thus have not led to the resurgence of Detroit, which is still encountering economic and population shrinkage. Furthermore, the possibilities for public interventions by the city administration are drying up due to the recent bankruptcy of the city. Nevertheless, in recent years more and more positive stories about the come-back of Detroit can be heard, but where is this optimism coming from?

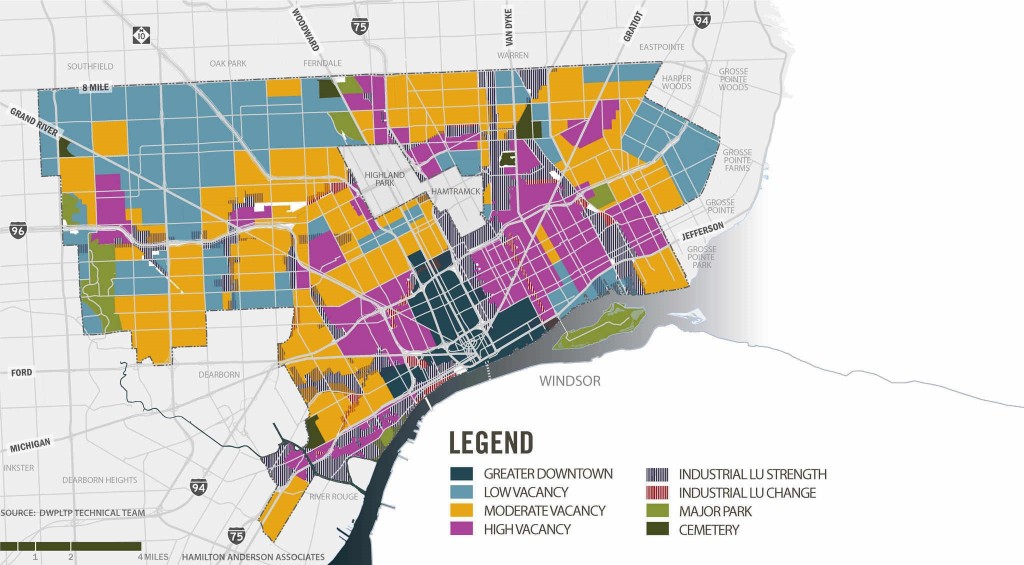

Map of Detroit showing the spatial mismatch between the population and location of jobs (Source: Detroit Works)

Urban Ruins turned into artist inspiration

When cycling through Detroit, there is no way to neglect its industrial past and how this shaped the existing physical environment. Forces of suburbanization and global economic shifts have been changing the landscape of Detroit: what remains are the carcasses of its former glory. These ‘urban ruins’, however, provide inspiration for many grass-root artists, with the Heidelbergproject as the famous example of how urban decay can be turned into a community-building art project.

The Heidelbergproject: Jellybean house representing racial harmony (photo: Authors)

Where the Heidelberg project might have started as an act of disparity to draw attention to urban decay and worsening circumstances in the Detroit neighborhoods, art is nowadays more and more applied as a tool to increase the quality of public space. Old run-down and abandoned industrial areas are being revitalized by using urban artwork and graffiti, and the city and its inhabitants enhance the image of Detroit as an art-city. This image is also projected in lively places as the Eastern Market, where wholesale meets music, art and restaurants. What seems to be different this time around is that entrepreneurs from outside Detroit are also seeing the beauty and uniqueness of Detroit’s urban ruins and manufacturing past. Creative companies embrace the history of Detroit and use the available industrial space as creative input in their production process. More and more companies are drawn to Detroit’s arty, rough and industrial image. Shinola, a successful company that specializes in the craft-production of watches and bicycles, is an example of a firm that deliberately chose to settle in Detroit because of its industrial heritage and creative energy. Shinola is proudly using ‘made-in-Detroit’ as its products trademark.

The establishment of companies like Shinola attracts new people and facilities to downtown and midtown Detroit, changing the landscape of the city in a surreal mix of urban ruins and ‘pockets of coolness’. As visitors, we enjoyed this new vibrancy, and the positive energy of locals who are proud to be part of a changing Detroit!

The Detroit Institute of Bagels: a new hip Bagel-bar (photo: Authors)

Unique entrepreneurial niche

The resurgence seems to come from entrepreneurs that adopt the beauty of Detroit’s industrial heritage and embrace the unique features of the city. Revitalization of the city is not achieved by large scale public investments alone, but rather seems to be fueled by private inputs that tapped into an entrepreneurial niche created by Detroit’s enthusiastic creative scene. The city of Detroit has little choice but to facilitate the cult-image the city has inherited. However, in order to integrate this attractive central area with the surrounding neighborhoods that are still excluded from the suburbs further away, a more comprehensive public transit system seems to be a necessary condition for a successful comeback on the long run. Projects like the construction of the M1 light rail are a hopeful start of putting the right conditions into place, in order to bring about a long lasting, vibrant and robust resurgence of the Motor City!

Skadi and Maarten made a trip to Detroit during their semester at Northeastern University, where they take part in the programme ´Urban and Regional Policy´.