Something terrible happened to the city of Dresden, something which is perhaps indescribable and unprecedented anywhere else in the world. Dresden (Germany) is the first city which has been removed from the renowned UNESCO World Heritage List. The reason? A bridge was built. ‘A bridge too damaging for the great cultural site of Dresden’, says UNESCO. ‘A shame’, says I. The German city only enjoyed a brief time on as a World Heritage site, as it was listed in 2004 and was removed five years later. Using the Dresden case, I argue that UNESCO’s conservationist discourse is detrimental to cities. An argument about why UNESCO is treasuring the past while blocking the future.

Waldschlösschenbrücke

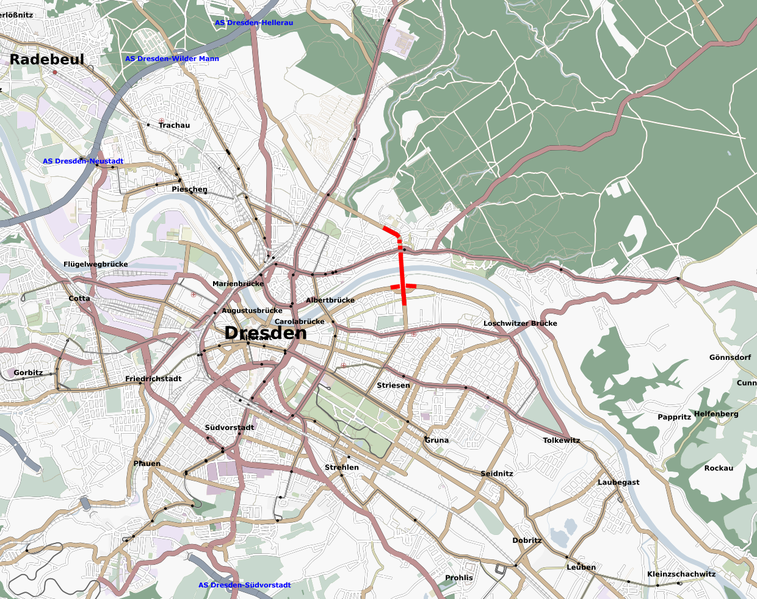

The Dresden-UNESCO conflict has everything to do with the development of the Waldschlösschenbrücke, a four-lane bridge over the Elbe valley. Due to traffic congestion on crossing points over the Elbe, the city decided to invest 182 million Euros to overcome this mobility problem, and started constructing the bridge in 2007. From the start, the bridge was not uncontested. Non-Governmental Organisations, as well as prime figures of Dresden’s cultural capital were protesting its development for reasons of environment issues and loss of cultural landscape. However, their legal proceedings did not stop the Waldschlösschenbrücke of being built, as they could not overrule the 68 per cent of Dresden’s voters which showed their support for the bridge in a 2005 referendum. Apparently, a large majority of the voters were in favour of the new traffic connection.

UNESCO’s fury

The reaction of UNESCO was furious, as it took the Dresden cultural site off of the World Heritage List. According to the UN heritage body, building the bridge was a display of ‘national disgrace’ and the new construction was detrimental to Dresden’s ‘outstanding universal value’. In their view, the Waldschlösschenbrücke was cutting through the 18 kilometre long stretch of cultural landscape of the Dresden Elbe Valley, directly blocking the view from the riverbanks on the 18th and 19th century skyline. So, what was enthusiastically listed in 2004, was brutally removed in 2009.

By delisting Dresden, UNESCO may have shown its engagement towards the aesthetically beautiful site of the Dresden Elbe Valley, but it has also shown that it is actively trying to block new developments. However locally accepted (i.e. 2005 referendum), UNESCO articulated, in their protest, their way of prioritising – an arbitrarily depicted – historical layer of the city. And exactly that point is problematic.

Dresden and its historical layers

Cities evolve over time. Not only because they need to in order to keep up with other cities in a highly competitive world, but they evolve for the simple reason that they embody environments where people live, eat, drink, sleep and work. The way people live their lives, and enjoy their direct surroundings changes constantly. Their human, social and cultural capital facilitates new ways of living, and may even generate new collective cultures, eventually finding articulation into the outlooks of the city. By prioritising just one particular historical layer of a city, as UNESCO is doing with regards to the 18th and 19th century layer of Dresden, it is prioritising this particular past, while simultaneously blocking any change which might benefit the city in the future. It is using a – close to arbitrarily depicted – historical layer, whereby all the other possible historical layers (be it 20th century, be it 16th century) always need to be severely negotiated before they find integration in the cityscape. This prioritising is especially detrimental to cities when it wants to develop for future demand.

It is not argued here that cities should get rid of these particular historical layers, as these are hugely important to a cities’ identity. Also, it is not argued that cities should just demolish everything so to make room for fast development (as might be happening in tremendously fast growing cities such as Guangzhou or Istanbul). Neither is it argued that new developments are always to be welcomed without questioning their integration with former layers of the city.

However, what is argued here, is that new constructions that support a city’s development, and are therefore well-thought through, should not be blocked just for the sake of a perspective which holds on to a historical layer which in itself has changed already. Cities change, and the historical layer we are now so eager to hold onto has already been a facelift on former outlooks of the city. It would seem that the old is always better and needs prioritisation, but who says that the new could not be integrated within the old? In the end such a mix will eventually be even more interesting and entail even more historical layers than a city which is well-preserved but will become nothing more than an entertainment park for tourists. And if this will be the case, the liveability of these cities will be in a rather corrosive state. It isn’t unthinkable that these kinds of cities, in the end, would lose the core of their identity: its people.

Treasuring the past while blocking the future

UNESCO undoubtedly works out of a genuine love for cities, and its aims are undoubtedly intended to celebrate the world’s diverse set of cultural sites. But UNESCO should be aware of the fact that its pivotal role in conserving heritage sites is positioned in a world of change. The mechanism they use now is one in which new developments are not able to get integrated, while this integration would be in the end the most desirable. UNESCO may fight for their genuine cause, but should simultaneously accept that urban environments, whatever historical layer finds prioritisation, are environments of people and should facilitate their views, their behaviour and their lives. In the case of Dresden, UNESCO has surely taken the conflict too far by delisting the city. Festivities on the bridge, a day before its inauguration in late August, has perhaps been the best way of showing UNESCO that new developments should take place to keep the city going and to develop new historical layers: 65,000 Dresdeners, celebrating the bridge, while simultaneously overlooking their city’s magnificent – historical – skyline.