19 March 2014 was a historical day for the city of Amsterdam. On this day, the ‘Kremlin at the Amstel’, which was one of the rather cynical nicknames of Amsterdam’s city hall due to the decades of hegemony by the local labour party, has fallen. Since WWII the party had always been the biggest. Hence, the Dutch capital was a reliable strong hold for the social democrats. Where the labour party lost, others won. Big winner of this most recent elections was D66, who are presenting themselves as progressive and pragmatic, or ‘social-liberal.’ This striking shift in the political landscape raises questions. Can the collapse of labour be regarded as a one-off incident, or is this electoral outcome a logical result of Amsterdam’s recent demographic and socio-cultural changes? To what extent are similar patterns visible in other European capitals? And is there a reason to worry about a growing urban-rural divide?

D66 is one of the political parties in Holland that has its own boat at Amsterdam’s annual gay pride (picture by Geoff Coupe, flickr)

Electoral geography: neighbourhood effects on voting?

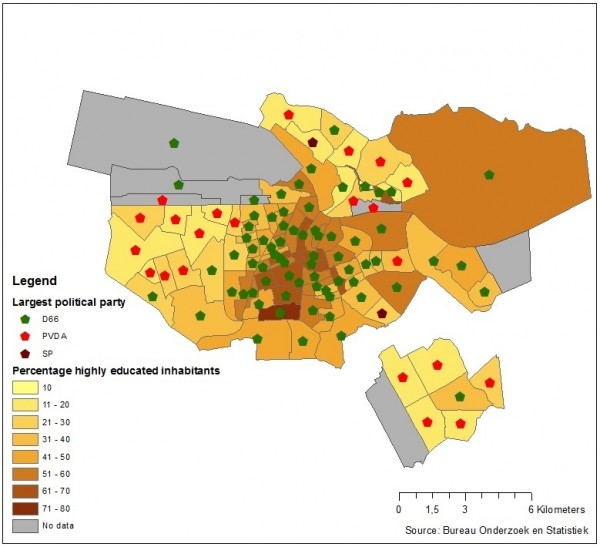

Scholars from different fields of study have thoroughly investigated voting behaviour: which factors mainly determine one’s political preference? Throughout the years, studies from different countries signal evidence that, apart from several lifestyle-related variables, gender, sexuality, age, media and even the weather on election day all have a certain impact on political preferences as well. From all these different disciplines, electoral geographers are mainly interested in spatial patterns of voting behaviour, and whether one can define a neighbourhood effect in terms of party popularity. The degree to which such an effect exists obviously depends on many factors: cultural (do people still tend to ‘belong’ to a certain ‘pillar’?), spatial (what are the characteristics of a particular neighbourhood?) and political (how many different parties can someone vote for?). In the case of Amsterdam, spatial patterns regarding last year’s electoral results are evident: the centrally located neighbourhoods, within the ring road A10, which recently have been increasingly accommodated by high-educated young people with an above average socio-economic status, seem to have developed a clear preference for D66 and the Green Party. The outskirts of the city, which predominantly consist of modernist social housing estates largely inhabited by people of Moroccan, Turkish, Surinamese or African descent, remained more loyal to the labour party (PvdA).

Neighbourhoods categorized by the percentage of highly educated inhabitants along with the largest political party of the 2014 municipal elections. Central Amsterdam is clearly dominated by D66, whereas the outskirts mainly vote for the socialist and labour party. Map made by Jonathan Dullemans

What does the hipster vote?

Cities are everything but static entities: most readers of this blog are probably aware of the fact that many European capitals’ urban economies are currently changing (adapting to what Allen Scott calls the ‘cognitive-cultural’ era), and likewise does their physical appearance. Processes that come along with these urban transformations are often described by using popular terms as ‘gentrification,’ ‘yuppification’ or ‘hipsterification’. Amsterdam is definitely no exception: a person that visited the city in the 1970s or 80s and returns today has the feeling that he has entered a remarkably different city: homeless people, drug dealers and ordinary working class people mainly disappeared and the cityscape is instead being dominated by hip coffee bars, fashion boutiques, organic supermarkets, and the like. This is the case in the touristic red light district, but also increasingly in the 19th century areas surrounding the city centre. Young people that perfectly resemble the stereotypical hipster-image are so plenty that people started to refer to the Dutch capital as ‘Hipsterdam.’ As Proto City author Cody Horstenbach has shown, the city’s municipality (including the former PvdA-led coalition) is actively stimulating gentrification processes, which partly explains the city’s rapid demographic transition. Whilst it was the main concern in the 1980s that Amsterdam would become a city dominated by lower-educated households, today people worry about exactly the opposite.

Has Amsterdam’s labour party dug its own grave by encouraging this development? Can it be hypothesized that social democracy does not quite appeal anymore to the majority of this new generation of Amsterdammers? Can international subcultures as ‘yuppies’ and ‘hipsters’ be generalized by assigning a certain political preference to them? Regarding the latter, opinions seem to be divided. However they are often described as having ‘progressive’ values, others assert that hipsters are products of the global trend of individualization, and therefore rather indifferent about social issues. Anyhow, it is interesting to see that northwestern European capitals show similar electoral shifts, as Josse de Voogd pointed out in his interesting article ‘Redrawing Europe’s Map.’ He stresses that gentrified (often 19th-century) neighbourhoods indeed have developed a clear preference for progressive parties (social liberals and greens). Examples are Nørrebro in Copenhagen, Södermalm in Stockholm, De Pijp in Amsterdam, Prenzlauerberg in Berlin, and Neubau in Vienna. Even Paris, a traditional rightist (!) stronghold, is now facing electoral shifts due to an influx of yuppies.

Street art collective ‘Kamp Seedorf‘ made a fake street sign displaying ‘Hipstergracht’ last year in Amsterdam’s city centre

Power to the cities?

De Voogd also addresses the growing socio-cultural and its consequential electoral gap between central urban space in Europe and its surrounding suburban countryside. This creates, in his words, ‘a rightist commuter-belt around these cities.’ In the Netherlands this is reflected by the support for the Euro-skeptical anti-immigration party of Geert Wilders, which gains a lot of support in smaller cities near Amsterdam, as for instance Purmerend and Almere.

Recently there has been a fair amount of attention for Benjamin Barber’s book ‘If Mayors Ruled the World.’ According to his view, nation states are not able to properly deal with the world’s current main challenges. Instead, he argues, cities offer the best new forces of good governance. And Barber is not alone. Aforementioned Allen Scott foresees ‘the emergence of an archipelago of global-city regions that is overtaking national states as chief territorial-organizational nexuses.’ Is it indeed desirable to strive for this ‘democratic glocalism’? If ‘global cities’ continue to become like-minded progressive-elitist heavens, will this then indeed bring us closer to solving the world’s major problems? Or will it rather cause an increasing divergence within (European) societies between the so-called winners and losers of neoliberal globalization? In her new book ‘Expulsions,’ Saskia Sassen warns about this explicit trend of spatial inequality, by pointing at extreme cases in Africa. In Angola and Nigeria for instance, small urban elites in respectively Luanda and Abuja get state support on behalf of the country’s less well-off parts. European nations such as the Netherlands of course have longer traditions of redistributive policies, and hence it is not likely that the urban-rural divide will suddenly become that extreme. Nevertheless, in light of those increasing globalizing trends and pressures, Amsterdam should not forget to keep caring about its hinterland (even though it might be hard to define exactly what this is) as being a ‘responsible capital’. Simultaneously, the question comes up again which direction D66-dominated (?) Amsterdam wants to go in the future. The city is, though merchants in the 17th century already had the desire, and apparently some of its inhabitants still do today, not a republic on its own.