‘’Dorcol is the neighbourhood where things happen and at the same time represents the oldest and the most prominent part of the city. Living in Dorcol has its charms, it could be like living in Kreuzberg in Berlin or Manhattan in NYC.’’ (Still in Belgrade, 2015).

This above quote is one of the first things that one will find when searching for the neighbourhood Dorcol on the internet. Indeed, it is not the picture that we had in mind before, or that one would expect in the first place when thinking about Belgrade in general. It is rather recent that this image of being a hip neighbourhood came into being. In 1981 a Serbian author, Svetlana Velmar-Janković, published a novel called Dorcol. In this fictional novel, Dorcol is not quite presented in a positive way. Its architecture is described as modest, including crossroads with limited human interaction, while the area is perceived as a dark space in which there is little possibility of making decisions and energizing oneself (Norris, 1994). Later, in 2000, the movie Dorcol Manhattan came out, which provided a more positive and trendier picture of Dorcol, which illustrates that its image gradually improved. Today, the neighbourhood is described as above and as ‘’a downtown area that features many of the city’s best cafes, a collection of caffeine houses that are as committed to good coffee as they are stylish interiors’’ (The Culture Trip, 2018).

Although the abovementioned sources are not scientific, it gives a clear impression of what the area is most associated with. Altogether, one can say that Dorcol at first sight seems to be a prime example of recent Eastern-European gentrification. For this reason, we examine to what extent this ‘new’ image of Dorcol is indeed accurate.

Research Methodology

This blogpost is the product of an assignment that was conducted for the course City Matters at the University of Groningen, which is given by dr. Barend Wind. In March 2019, an excursion to Belgrade was organised as a part of this course. Related to the context of the course, we adopted a combined perspective of gentrification and social justice through which we have studied Dorcol. Gentrification, namely, can cause displacement of local residents as soon as ‘too much’ of the working class is displaced by middle-class quality, -residents or commercial use. In order to determine the social justice threshold in Dorcol, we used the sufficientarianism principle of social justice (Vallentyne, 2007). In other words: A situation is (un)just if, and only if, a certain sufficient level is met. An example could be the minimum wage in a country. Mostly, sufficientarianism tells us something about a static point in time, whereas gentrification is an ongoing process. However, since we focussed on the degree of gentrification at a certain moment in time, we saw sufficientarianism as an appropriate indicator for our research.

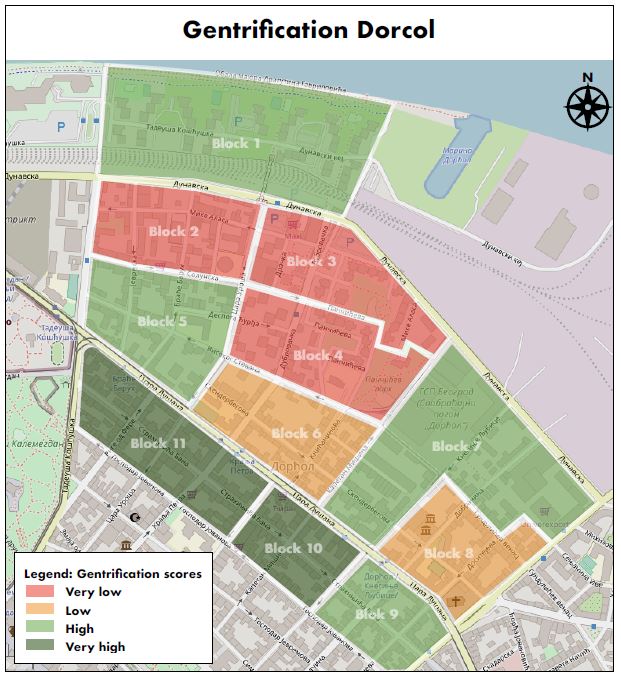

While looking at over 500.000 transactions in the Netherlands, Visser and van Dam (2005) argued that characteristics of houses, residential environment and the location are great indicators for house prices. Subsequently, a recently published paper by Bajat et al. (2018) shows four different groups of determinant factors that influence property values and rental costs in Belgrade: structural, accessibility, neighbourhood and environmental factors. Based on the property values found by Bajat et al. (2018), we divided Dorcol in eleven blocks (see Figure 1). Additionally, one would expect a variety between the different blocks in terms of the aforementioned indicators. Thus, in every block we assessed 1) the quality and mix of the buildings and types 2) the quality of the public spaces and 3) the amount and prices of facilities and services, such as a café or supermarket. We attached scores to every observation, so that every block eventually got a ‘gentrification score’, ranging from very low to very high. Linking the observations and neighbourhood blocks to social justice theory, we assumed that it is sufficient if at least five of the eleven blocks score low on gentrification. This means that, if this amount is reached, there are still enough places where the original inhabitants can live which makes the degree of gentrification just.

Degree of Gentrification in Dorcol

In Figure 1, the gentrification scores of the eleven blocks are presented. It can be observed that five of the eleven blocks are not (yet) gentrified as their scores are low or very low. Reflecting on the social justice framework, we therefore can conclude that in Dorcol there is still enough place for local residents to stay put. The aforementioned sufficient level is namely not yet exceeded at the time of the excursion. The gentrification process in the neighbourhood of Dorcol is thus indicated as socially just.

Discussion

Although the gentrification in Dorcol is indicated as socially just, we must keep in mind that gentrification is an ongoing process. There is a risk that the degree of gentrification in Dorcol will continue because of various developments in Dorcol and the heavily debated Belgrade Waterfront project at the other side of the river crossing point of the Danube and Sava, which is currently under development as seen in Figure 2[1]. Also, our field work indicated that blocks 10 and 11, to the south of Dorcol (city centre side), are most gentrified. The gentrification process is thus evolving from south to north. Block 1 is an exception in this regard, due to its location at the waterside. Hence, it includes many bars and recreation facilities, and the railway line which functions as a physical barrier. Right now, Dorcol is experiencing the so-called positive first-generation wave, which results in an attractive neighbourhood in which local residents are not displaced directly. Lower incomes can possibly profit from this development as well. Over time, the more often negatively perceived second and third generation of gentrifiers will enter Dorcol, which can push out local lower income people due to increased property values, according to Lees and Slater in their book the gentrification reader. This is usually the moment that gentrification exceeds its sufficient level.

Figure 2: The current demolition of the central railway station in the city of Belgrade with the Belgrade Waterfront project developments on the background.

Concluding remark

Looking back at the quote about Dorcol, we can indeed say that the ‘new’ image of the neighbourhood is present to a different extent. In block 11, various restaurant and bars are found, whereas in the less gentrified block 3, the urban environment and its purposes are still about living and recreation only. Moreover, block 7 contains the famous Dorcol Platz, which is an old industrial site that is transformed into a ‘hipster’ place and bars to hang out. So, it could be argued that the neighbourhood image is gradually changing while it anticipates on its attractive location next to the city centre, and the increasing tourism sector which is stimulated by the national government.

- Dorcol Platz in Block 7

- Typical restaurant in block 11 in Dorcol

- Playground in-between residential flats in block 3

Contemporary urban developments in Belgrade, as opposed to the country’s socialist past, indeed tend to have a remarkably neoliberal character. Neoliberalism in this sense refers to attracting international capital, an open, competitive and unregulated market, and decentralisation. Governments herewith try to improve the competitive advantage of cities compared to others. This is, for example, seen at the Belgrade Waterfront project that involves investors from the UAE, the tourism sector that the city of Belgrade is increasingly focussing on, and the idea of ‘urban entrepreneurialism’ (Harvey, 1989). More concrete, the recreation options in Block 1 and the upgrading facilities, like Dorcol Platz in Block 7, are the outcomes of this market mechanism. Unfortunately and luckily, gentrification is a result or consequence of this way of these urban planning policies. And, indeed, gentrification does bring advantages to a city or neighbourhood, especially in the pioneering phases. Still, however, one must be aware of the pitfalls that gentrification can cause in the long run in order to safeguard a socially just urban environment.

This article is written by Stefano Blezer and is about the visit to the city of Belgrade in March 2019. The research was carried out with Jorrit Kootstra, Jeska de Ruiter, and Daniëlle Ruikes. The visit was part of the course City Matters; a course focussed on (in)equality and social justice in the built environment for students of, among other master programs, the MSc. Socio-Spatial Planning at the University of Groningen. The pictures and map used in this article are made by the authors.

[1] Read an article by an architect and a member of the main activist group Ne da(vi)mo Beograd (Don’t let Belgrade D(r)own) or check the official website of the BW project for more information and insights.