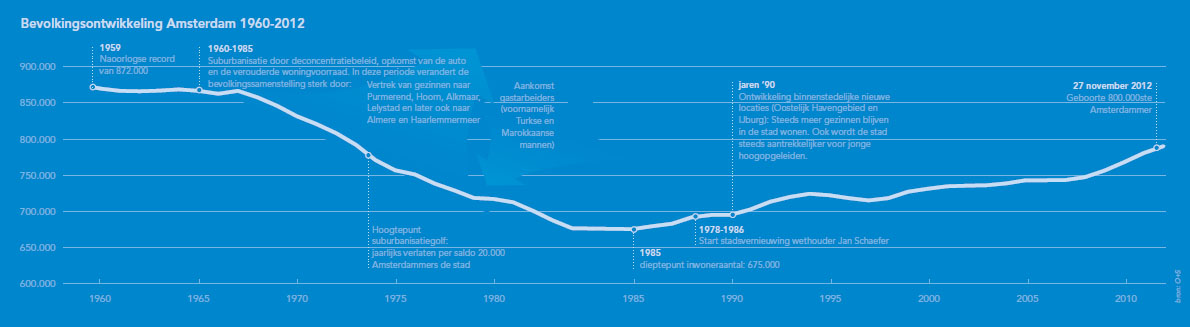

Amsterdam is in great shape! Everywhere I attend lectures and seminars of urban professionals this statement is made, before more detailed issues are discussed. And quite frankly, those professionals are not mistaken. After an extensive era of urban renewal and suburban flight, in the late 1980s the city and region recommenced developing economically in line with ideas of Florida and Glaeser: the service economy took shape with Schiphol Airport and no longer the harbour as its engine, with students, entrepreneurs and office workers and no longer industrial workers as its fuel. After hitting rock-bottom the population started growing again after 1985:

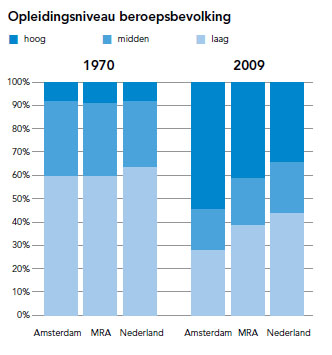

And Amsterdam has increasingly become a city of the highly educated workforce:

Education levels of Amsterdam, the region and the country 1970 – 2009. Source: O+S Amsterdam

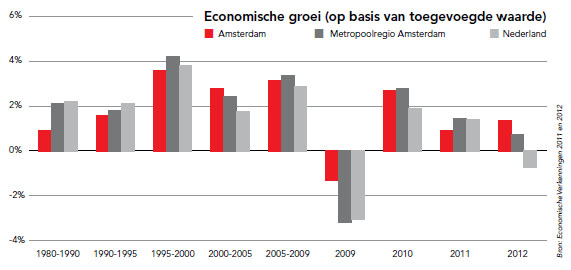

Economically Amsterdam started to catch up with the country as a whole, and the city and region are in fact outperforming the country in the recent crisis-ridden years:

Economic growth of Amsterdam, the region and the country 1980-2012. Source: O+S Amsterdam

However, there is a flip side to this story, a nuance in need of clarification. The success of the city will heavily affect the future and the current economic crisis shows that this path of development of the last decades is not without risks. The city awaits a debate on which direction it should develop into in the coming decades. The successes of the past and current crisis can be roughly used to paint two images of an Amsterdam for our future generations. It is up to everyone in the city to decide which way to go, it is by no means an objective of the city’s planners and politicians alone.

Parisian Amsterdam

The first image of the city is one painted by many urban professionals of various backgrounds active in Amsterdam: civil servants, real estate developers and architects. Amsterdam is the ultimate success city of the Netherlands, with on the one hand its museums re-opening, attracting tourists from all over the world, boosting hotel development and the service economy and bringing worldwide fame and accessibility. On the other hand its success is in small-scale urban fabric, ideal for small businesses, cafés and restaurants along the city streets. Especially the ‘winning combination‘ of the picturesque late-19th century architecture and the pre-modernist urban plan in various areas of the city provides this small-scale urban space.

The crucial feature of this image is that it is strictly confined to the central areas of Amsterdam. With the economic and demographic growth of the last two decades it has extended into the 19th century belt around the old city centre, and in the recent years attempts have been made to further ‘roll-out’ this image of the city along and even across the A10 ring road. Amsterdam’s spatial planning policy documents such as the 2040 vision of 2011 and more recent strategic plan (2013) are promoting this direction of thinking, although some of its planners are of the opinion that the post-war urban fabric will not be able to absorb this type of development.

This image of the city is favoured by many of the usual suspects in urban development, as it promotes the further development of attractive milieux of the city, in order to, according land prices and profits, accommodate the highly educated, two-income households, with high purchasing power. Success of these groups should increase opportunities for all, with increasing economic activity and trickle-down effects.

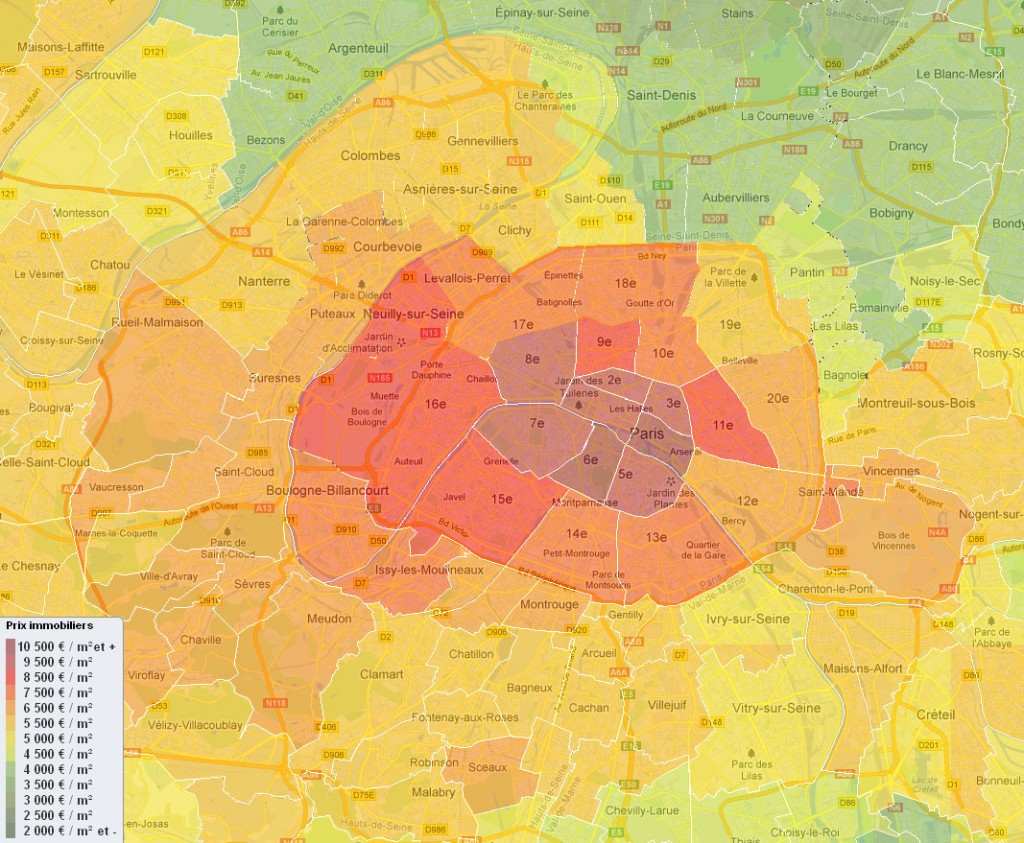

This is where the Parisian comparison comes up, a city with a very valuable, expensive urban centre, increasingly rolling outwards:

In Amsterdam similar, though far less intense (see price levels) images are already visible:

Although the effects in Paris are much more dramatic, Amsterdam could rapidly go in the same direction, creating a city of two realities: the central city with its economic importance, and less desirable areas surrounding it with affordable housing for the less affluent.

Berlinian Amsterdam

The image of a Parisian Amsterdam is a tempting one, focusing on the successes of Amsterdam’s urban development (both economic, demographic, real estate and infrastructure) of the last two decades. However, since the economic crisis hitted the Netherlands, including Amsterdam (unemployment now rapidly rising), the doubts of a continuing success story increased. Some even mention the ‘real-estate dream that turned out to be a nightmare’ a major cause of the current economic problems and a barrier towards future solutions.

The Parisian Amsterdam also passes by the existence of the Arrival City, and the strong separation of attractive and non-attractive urban space created with it:

Beyond the ring road there is another reality of urbanity. While large investments are made in these areas as a part of the latest urban renewal programs, these neighbourhoods still lack the qualities of the city centre and seem to draw the shortest straw as the public spending cuts decrease the future opportunities for their inhabitants.

In the image of a Berlinian Amsterdam however, an alternative mode of development is envisioned, in which a variety of multiple urban milieux is much more important than the success of just one. Berlin is an example of a city that has been deprived from public investment for more than a decade now, but is very successful in facilitating bottom-up development.

This image of Berlin shows on the one hand that not necessarily the usual suspects of urban development need to be leaders in shaping the future of Amsterdam (although they can be). On the other hand, it shows that alternatives to the public administrative visions and strategies are possible. When zooming in on an area like Amsterdam Nieuw-West, such an alternative becomes visible.

Amsterdam Nieuw-West renewal efforts: Andreas Ensemble under construction. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Whereas the urban renewal efforts have attempted to differentiate the inhabitants, and make the area attractive to both local and city centre milieux (especially along the A10 ring road), independent developments have transformed large (and more remote) parts of the district much more explicitly:

Tanger Verscentrum in Amsterdam Nieuw-West expanding with an extra floor for supermarket space. Source: Flickr.com, CarnagerSDV

Local ethnic entrepreneurs have transformed the slowly dilapidating 1950s modernist shopping streets (due to lack of public maintenance) into a pleasant mix of shops and super markets. Despite the negative image with urban planners, some local entrepreneurs managed to create regional and sometimes even national importance for their niche markets and are heavily investing in their businesses (such as Tanger, pictured above).

Another example is the willingness of Turkish families in Nieuw-West to invest in CPO housing projects (collective private investment groups), that require large funds and long term dedication. Originally these projects were aimed at drawing interest from outside the district. This proves alternative development processes that up to now have hardly been recognised as important for the future of the city.

Claiming ownership of districts, neighbourhoods and areas by local inhabitants and entrepreneurs that up to now have been lagging behind the development of Amsterdam’s central areas is the key feature of the image of a Berlinian Amsterdam: a variety of speeds and realities of urban development.

Crossroads

Amsterdam is at crossroads, will the economic crisis soon fade away and the pressure on the urban development return and create a Parisian Amsterdam? Or will the growth of the past decades not come back, and should the city rely on a Berlinian pattern of development?

Both ways have their positive and negative elements. Neither will evolve exactly as I explained them here, nor do we have a set of tools that allows us to. The crisis has brought new insights: a development pattern such as Amsterdam has gone through has created a highly successful city, while in the recent years the stalling engine of development has laid bare alternatives that are worthy components of the city and important to not lose out of sight. Let the debate commence!