With almost 17 million inhabitants, Istanbul is Europe’s largest city. It is almost unimaginable that this metropolis had a population of less than three million only thirty years ago. The deplorable state of the economy and tensions between left- and right-wing political organizations, which led to a military coup in 1980. All governments after this coup tried to enhance Turkey’s economic situation with massive neoliberalization programmes. All growth became concentrated in Istanbul, whereas industries in rural towns went bankrupt soon after.

From that moment onwards, people from all over Turkey’s countryside and smaller towns realized that moving to Istanbul would be the only option to get a better life. Istanbul experienced an almost unstoppable growth. The documentary Ekumenopolis shows in a fascinating way how this process unfolded. Because of this massive internal migration, Istanbul became the largest Kurdish city in the world. Around three million Kurdish people live in the city today, 1,500 kilometres away from what could be called their homeland. What are the living conditions of the Kurds in Istanbul? And what role does being Kurdish play in their daily lives?

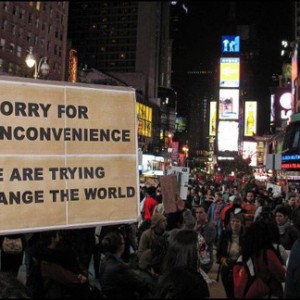

Kurdish women part of the supply chain for sweatshops in neighborhood Demirpaki (Photo: Barend Wind)

The Kurdish Migration

Contrary to other Turkish migrants, the Kurds are not mainly economic refugees. Many of them migrated because they fled Kurdistan due to violence from the Turkish army. Since the establishment of the modern Turkish state in 1923, the government has forced all minorities to ‘become’ Turkish. For the Kurdish population, this meant that their language, symbols, and traditions were banned and suppressed in a brutal way. Those who refused to speak Turkish, or simply did not know the language, were humiliated and beaten. The ones that organized insurgencies against the new central state were murdered by the Turkish army. Fear for repression silenced the Kurdish opposition.

It took until the late 1970s for the Kurdish people to wake up again. Of the many movements that were founded, the PKK is the most famous. Since the beginning of the movement in 1978, it combines leftish ideals of solidarity and brotherhood with a struggle to liberate Kurdistan and to unite the Turkish, Iraqi, Iranian, and Syrian territories. In the guerrilla war that followed, the Turkish army burned down the houses of those who did not obey the state. Many Kurds were thus forced to move to Istanbul. Others moved voluntarily. The Kurdish migrants often ended up in gecekondus (neighbourhoods built overnight) at the periphery of the metropolis. Many years passed by since then, but the Kurdish issue remains unsolved.

In the meantime, Istanbul’s Kurdish neighbourhoods became varoşes (ghettos with permanent apartment buildings) and became integrated in the urban fabric. Nowadays, they consist of permanent apartment buildings with four or five floors. Although these neighborhoods do barely differ from the Turkish working class neighborhoods that surround them, the Kurdish neighborhoods are considered as varoş (ghettos). When I asked an employee of a luxury hotel in the city center how to reach Demirkapi, a notorious Kurdish neighborhood, he answered straightforward: “Don’t go there. It’s dangerous. I hope you come back alive, my friend. I hate the pigs that are living there.”

It sounds Demirkapi is worth discovering.

Youngsters dominate Demirkapi’s streetscape (Photo: Barend Wind)

Daily Life in Demirkapi

Entering Demirkapi is entering a different world. Although the buildings look similar to those of the surrounding neighborhoods, the atmosphere is different; the air breathes an almost revolutionary spirit. Whereas the rest of Istanbul is pretty clean, in Demirkapi one can find litter in every porch and at every street. The local leader of the BDP (a legal Kurdish political party, affiliated with PKK) explains that it is common that the municipality does not collect garbage in Kurdish neighborhoods.

Another difference with the surrounding neighborhoods is the larger amount of youngsters on the streets. When you are young in Demirkapi, it seems that only two options are available: getting involved in Istanbul’s drug scene or working in one of the many sweatshops where T-shirts and jeans are produced for the Western market. Possibilities for social mobility are almost absent. Most finish primary school, but only a handful reaches a higher education degree. In recent history, it was not uncommon that these youngsters joined the PKK guerilla forces when they grew older.

Many residents are employed in one of the sweatshops where clothes are produced (Photo: Barend Wind)

In many ways, the state treats Demirkapi’s Kurdish population as inferior. In that respect, the failing system of garbage collection is only a minor issue. More serious is the fact that the government does not aim policies at increasing life chances of the Kurds. Instead, as is argued by some of the residents, the state supports Turkish criminal organizations to fight Kurdish clans. In doing so, they stimulate drugs use among the Kurdish youth. The stance of the state is quite understandable when one realizes that drugs addicts will not be able join the guerrilla forces in southeast Turkey.

For the residents, it feels that the war in Kurdistan continues on the streets of Demirkapi. To survive in this hostile environment, many Kurds count on their own ethnic neighborhood organizations to make the ends meet. Especially the BDP plays a central role. In the small party offices, inhabitants come together for a coffee to discuss politics and for social support. However, these neighbourhood organizations fear for their existence, since the state uses all means to frustrate their functioning. Without exception, all party leaders have been in jail for years. One of the attendees of a BDP meeting stresses that “the police put drugs in your pocket when you are innocent, to get you sentenced.”

In front of the BDP office, a mother shows a picture of her son who was killed in the conflict (Photo: Barend Wind)

Dreams of the Homeland

Daily life in Demirkapi is heavily influenced by the Kurdish struggle in southeast Turkey. The state actively punishes people for being Kurdish and for sympathizing with those who fight for an autonomous Kurdistan. However, the harsh living conditions and the ubiquitous PKK graffiti are not the only signs of the conflict that takes place in the ‘homeland’.

Even more pronounced are the mental scars of the parents who lost sons, fighting in one of the guerilla groups. Impressive is the story of one of the Mums for Peace, a group of mothers who lost children in the Turkish-Kurdish conflict. In front of the BDP office, she shows a picture of one of her sons. “He was killed by the Turkish army, when his guerilla group was attacked,” she explains. Her other son fulfilled his military service in the Turkish army. PKK guerrillas killed him. Fortunately, the war between the PKK and the Turkish army has been less severe in recent years. Under international pressure, and in order to seek support for his government, Erdogan granted the Kurdish population some cultural rights. In return, the PKK and the Turkish army signed a ceasefire.

Although the military conflict seems to be frozen, the economic war in Demirkapi continues. And when will Kurdistan be liberated and become autonomous? “Around half of the Kurds will leave Istanbul to settle in our homeland,” expects a resident of the neighborhood. For those who will remain in Demirpaki, the struggle for an independent motherland will be over, but the struggle for workers’ rights, advocated by Kurdish political organizations, will remain important.