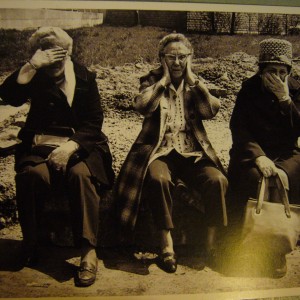

An attempt at colour on Istanbul’s urban fringes (Photo: 130325.011 by Adam Nowek)

It is a well-known fact that Istanbul can be found high on the list of mega-cities experiencing a high earthquake risk after Manila, Jakarta, Lima, and Santiago due to its geographical location on the boundary of three different tectonic plates. It is not a question ‘if,’ but ‘when’ Istanbul will be hit by a devastating earthquake.

The 1999 Turkey earthquake resulted in more earthquake risk assessments for Istanbul (Erdik et al. 2003), since it is both economically as culturally by far the country’s most important city. Such a high probability of an earthquake is the expected event which is currently influencing the so called Urban Transformation Projects (UTP). Natural hazards endanger metropolitan areas and therefore urban transformations and mitigating disasters are grouped together. However, there seem to be underlying power structures and mechanisms for these currently on-going UTPs.

From Gecekondu to TOKI

Istanbul’s growth is mainly based on Turkey’s industrialisation which led to a huge rural-urban migration between 1945 and 1985. This period included a lot of self-urbanisation of migrants into the gecekondu (Turkish for ‘built overnight’) neighbourhoods. At the end of this period almost half the population of Istanbul lived in gecekondus. Such neighbourhoods are often directly linked to low socio-economic standards of living.

Following our natural hazard perspective, gecekondus do not seem earthquake resistant because they are built from makeshift materials and do not follow earthquake construction regulations. UTPs are supposed to ‘protect’ the urban poor of Istanbul’s inner city by replacing them to the outskirts into resilient housing compounds. These buildings are constructed by the Mass Housing Administration, TOKI, and sold for subsidised prices.

The Kayabaşı housing development is Turkey’s largest (Photo: 130323.013 by Adam Nowek)

Facts or Opinions?

TOKI has already received a lot of criticism from a mainly sociological discipline. An interesting source is Imre Azem’s documentary Ekumenopolis, where UTPs are criticised from the perspective of gecekondu inhabitants. Despite subsidised prices, the houses are still too expensive for a part of the urban poor. Also, the accessibility of the compounds is poor due to the lack of public transportation and commuter difficulties (some people are unable to operate their jobs after relocation).

Moreover, opinions are divided among and between stakeholders and academia concerning the earthquake stability of the buildings. The new housing schemes of TOKI meet the guidelines of being earthquake persistent. Taller buildings are supposed to be more resilient than lower buildings: they have a more flexible character.

Nonetheless, opinions in The Voice of America and Daily News present a more pessimistic view on the quake resistance of the new housing compounds. For example, the UTPs lead to an increase of population density which increases the risk of human losses. Another argument is that public firms such as TOKI are expected to have lower building standards and regulations compared to private firms. The pro- and con- arguments of the resilience of TOKI buildings are however feeble because both parties stay rather superficial in their argumentation. Also, individual interests seem to play a role in the argumentations.

Some parts of the compounds are inhabited and buses are running (Photo: 130325.014 by Adam Nowek)

The Real Motives

There seems to be an essential underlying structure in this whole process, namely the gentrification of inner-city Istanbul. In a previous article, Freek Janssens explained the neo-liberal motives behind a modernising Istanbul. This resulted in the closure of periodic marketplaces important for the transformative structures of the poorer neighbourhoods.

These modernisation motives can also be explained through the developments of TOKI in the old gecekondu neighbourhoods. The land of the old slum areas is partially developed by TOKI in order to produce funding for upgrading, focused on wealthy residents and tourism, residential complexes, and recreational zones. Although TOKI seems successful in supplying safe housing for the urban poor, the underlying mechanism is a growth paradigm whereby this same group has to make room. This is a process which happens all over the world. For example, after the devastating tsunami in 2006 which hit Sri Lanka and southern parts of India, the poor fishermen were relocated inlands due to safety regulations. Naomi Klein calls this ‘blanking the beach‘, because the now-empty beaches could be gentrified into a tourist area including luxurious beach resorts.

Can such disaster capitalism be projected on the UTPs of Istanbul? The only difference is that, in the case of Sri Lanka, an actual disaster was necessary; the earthquake stress on its own seems sufficient for Istanbul’s blanking of the inner-city.