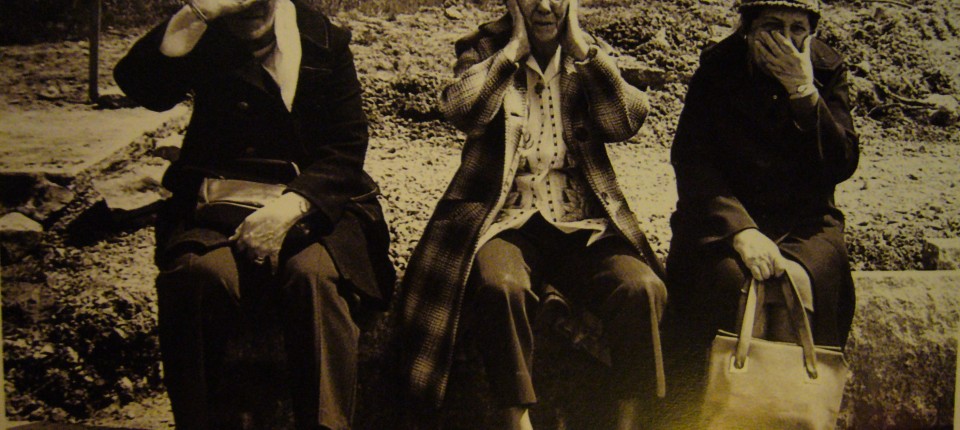

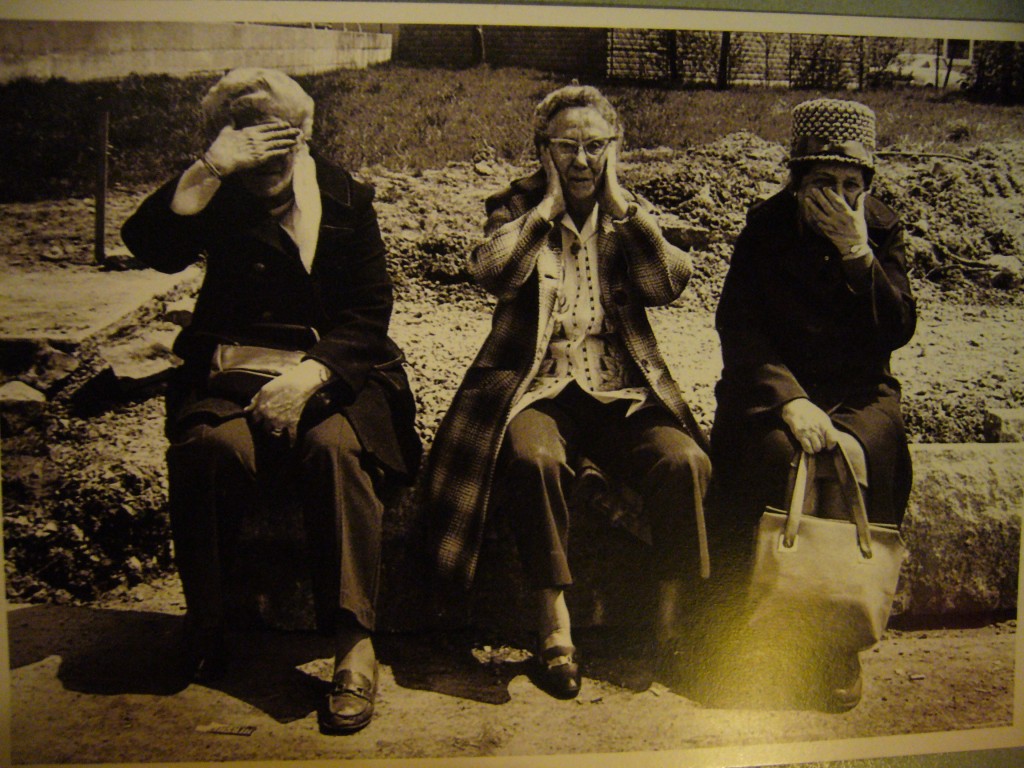

“Having dementia is very tough but having a city who excludes dementia that is really tough” (Bart Deltour, Foton Dementia Charity, Bruges)

Can’t see. Can’t hear. Can’t talk – Widespread Approaches Towards Dementia in Cities? (Photo made by Michael Corsi)

Buzz words and ideas revolving around ‘sustainable’, ‘age-friendly’ or ‘inclusive’ city making are relatively widespread and gained increasing momentum in the past decade. All of which aim to improve cities in one way or the other, calling attention to population groups or issues often left out of the discussion. Recently a new term and rhetoric has been put forward and enjoys growing attention in cities across the world –so called ‘dementia-friendly’ communities. Not (yet) something very typical to be found on urban planning and community development agendas. Given the increasing number of people diagnosed with dementia today, this will most probably change.

This short piece is not about how to prevent dementia (which researchers and medical companies appear to disseminate on a daily basis). It introduces and discusses the concept of ‘dementia-friendly’ cities by reference to Bruges, a Belgian city actively working towards ‘dementia-friendliness’. When thinking of dementia, rarely (practical) questions come to mind: How is it like for dementia patients to go about their lives and navigate in a city? Or what are the experiences of care takers, family members and friends accompanying them. Usually when dementia enters (public or private) discussions, images of nursing facilities and other care institutions (specialized or not) in patients with dementia are portrayed. It is those images (of mostly locked up, passive and very old recipients of care) and a lack of diverse portrayals of dementia that a ‘dementia-friendly’ rhetoric challenges and critically questions.

Best practices from Bruges?

Bruges is a small historic city in the Northwestern part of Flanders in the Flamish part of Belgium. With its approximately 117.000 inhabitants, the city attracts a lot of tourists due to its ‘fairylike’ medieval character and old city centre. Some readers might now also think about the movie ‘In Bruges‘.

Bruges, Belgium. (Photo by Adam Nowek)

Whereas Bruges is not an exception nor the only ‘dementia-friendly’ city, it is often referred to as a pioneer in developing dementia-friendly cities. Other examples around the globe include York (UK), Newcastle (Australia), Twin Cities (Minnesota, USA) and many more. A short BBC video introduces some of the cities projects – including a choir for dementia patients and their care takers, trained shop-owners aware of how to help lost or confused people (which appears especially important for people within early-stages of dementia). The picture below shows the sign that store owners in Bruges put into their windows to signal that ‘they are ready to help’. Additionally, efforts to collect information about citizens with dementia, as well as developing techniques to locate missing dementia patients by the local police are introduced in the video.

What does ‘dementia-friendly’ mean?

Dementia-Friendly Sign Put Up In Local Stores

Working towards ‘dementia-friendliness’ clearly does not only entail to adopt the physical landscape (providing accessible environments, ensuring places to sit and rest, which not only ‘serves’ people with dementia!) of a city. It is equally important to raise public awareness, foster social inclusion and to tackle stigmas about dementia.

It is about attitudes towards trying to make life easier for people with dementia and their care-takers – as well as everyone finding themselves in a situation with a confused or irritated person suffering from dementia, or memory loss. It is about asking how everyday activities such as going to the grocery store, taking public transit, going to the doctors, hairdressers etc. can be made easier for people with dementia and their care-takers. It is about reducing additional hurdles for people with dementia to carry on with their lives in their cities and find support by their communities. In these communities: people will be aware of and understand more about dementia. Furthermore, becoming or better working towards ‘dementia-friendliness’ is not something to be ‘achieved’ within a set time frame but rather an ongoing process.

Moving forward

Bruges can definitely be considered as showcasing good-practices and local projects around the ‘dementia-friendly’ agenda. Wondering about the translatability of some practices into a larger city I believe that some of the ideas (like specific signs to be put up in shops and making physical environments easier to navigate) are most likely doable within a larger city context. Moreover, it is also about adopting a certain attitude of actively including vulnerable parts of the population in making Bruges’ efforts a success story. It calls for common efforts to facilitate dialogues among different stakeholders in a city. The importance to raise public awareness about dementia and hint at shifts towards not only planning for ‘able-bodied’ citizens seems imperative!

Waiting in Bruges Trainstation (Photo by Adam Nowek)

One can debate about the meaning and significance of having buzz words such as ‘dementia-friendliness’. Nevertheless I do think they serve as a helpful common point of departure to start discussing and more importantly acting towards societal and urban challenges. A hairdresser in Hamburg advocating for awareness-raising about dementia and specialized trainings for shop owners, stated that ‘with all the talks about growing numbers of adults with dementia, negative images of an increasingly aging population, there needs to be (more) action and public awareness’. The ‘talk-only and wait game’ needs to stop. I agree. If we want to make cities enjoyable and accessible for everyone, planning for and with vulnerable population groups should be put to the fore.