Scaling the Housing Project

Planning is a profession. When a new housing development has to be planned, urban planners need to think of suitability, supply and demand, stakeholders’ interests, and feasibility, amongst others. But most of all, they need to question the scale of the project in combination with the demands of the local people they are planning for. In other words, is a new development suitable for the environment? What are reasonable projections in terms of housing demand? Given all these considerations, urban planning needs to be taken seriously. When this is not the case, things can go horribly wrong. This blog is about one of such cases: the Goese Schans, a big housing project in Goes, a city in the southwestern part of the Netherlands. I will show you what went wrong in the decision-making process, why it was too ambitious, too big, and how planners lost sight of the appropriate scale. But first, let’s introduce you to where this post is all about: the Goese Schans.

Introducing the Goese Schans

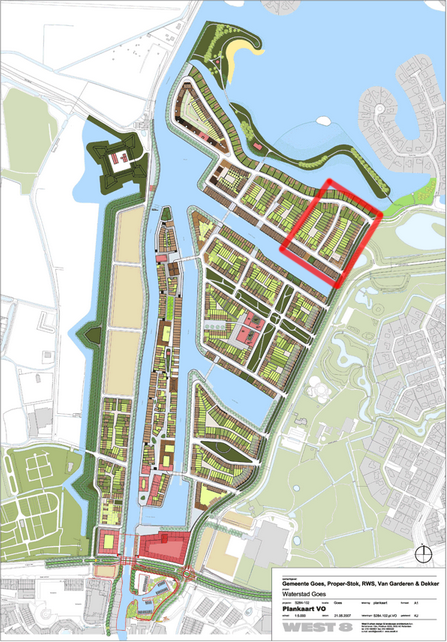

The Goese Schans is a planning project located in Goes, in the southern province in Zeeland. Goes is a small town with around 30.000 inhabitants, located in the least densely populated province of the Netherlands. Due to the fact that there are no big cities in its vicinity, Goes serves up to 100.000 people and is therefore recognised as the regional commercial node. Around 2005, the local municipality needed a new flagship to market the city and attract more people from outside its urban borders. The idea for the Goese Schans – Goes’ own starchitecture project – was born.

The ambition was to reinvent the old harbour area. Because the local government saw no abilities for the harbour to expand, the municipality concluded that the harbour – employing around 250 people – would not be functioning anymore in the near future. Not unsurprisingly, the municipality recognised the location’s high potential: close to the city centre, close to the water. As is happening in numerous other places around the world (i.e., Hamburg’s Hafencity, Amsterdam‘s Westerdokseiland, and Manchester’s Quays) they decided to introduce waterfront housing to give the port a new function. In others words, it is a perfect place for a combination of peaceful living, water leisure, and ‘authentic’ housing. New inhabitants would be able to park their cars in their private underground garages, get a cocktail in the open kitchen with panoramic view, and hop on their boats for some sailing relaxation: the perfect story.

With its planned development of 1.900 condos (of which 50 per cent were identified as ‘expensive living’), it would become close to the biggest neighbourhood of Goes and would let the city’s housing stock grow by an astonishing 11 per cent.

Goese Schans: Feasible?

But some things went horribly wrong. As the municipality did not own most of the harbour area, businesses needed to be bought out first as well as the respective plots. This operation was already fundamentally ambitious, but everything went on quietly. The initial investments were therefore excessive and millions of Euro’s were spent to be able to acquire the land in order to actually start building the housing blocks. But, we’re still talking 2008. The investments were just ahead of the start of the financial crisis, which basically froze the Dutch housing market. That’s a problem. But to stop here and quit the discussion on this housing project by basically stating it has failed due to the crisis, would be too easy, and wouldn’t give right to the actual fundamental fallacies in the initial plan. That is, the miscalculations urban planners made with regards to the feasibility and the appropriate scale of the project.

Neighbourhood Scale

The Goese Schans would include 1.900 condos. Projections were that half of the new inhabitants would be local people that wanted to move to something new, and the other half for people from outside the province that were looking for something incredibly unique. Taken the fact that almost half of the housing project was recognised as ‘expensive living’, one could only guess they were actively attracting the wealthy segments of the Dutch society: one part young urban professionals, one part retirees. The projection of attracting 50 per cent new inhabitants from outside its provincial borders seems bizarre. The strategy of how they wanted to achieve this was threefold. Firstly, it needed to be achieved by good marketing (‘smart’ advertising), secondly, by strengthening the Goese Schans’ cultural function (introducing events, liveliness, terraces) and thirdly, by exploiting the local physical capital (showing the water, experiencing the port). In terms of attracting from outside the province, this seems modestly ambitious and questions the feasibility on the neighbourhood scale.

City Scale

As is mentioned before, the Goese Schans would increase the housing stock of Goes by 11 per cent. In itself maybe not a shocking figure, if it wasn’t for the fact that Goes at that time was engaged in five other housing projects as well that would also enlarge the housing stock with around 10 per cent. However large the project of Goese Schans was, the Goese Schans was not the only focus of the local municipality. In other words, on the scale of a single housing project, the feasibility is already questionable, but this even worsens looking on a city scale. A commonly used argument that the effect of the reducing family size per living space would compensate for the gap between supply and demand is plainly overestimated. Hence, one immediately recognises the risk the stakeholders of the Goese Schans are taking when there is a huge initial investment to make, while there will be direct competition of other housing projects in its vicinity.

Goese Schans’ first development in 2011 with on the backdrop the port (Photography: Andres Muller)

Regional Scale

If that’s not all, the regional scale does not make the whole picture brighter for the Goese Schans’ prospective. The province of Zeeland is currently dealing with a shrinking population (also seen in other peripheral areas of the Netherlands such as Den Helder and southern Limburg). This means that the region’s population is declining which may threaten the vitality and attractiveness of the area in the longer run. However, Goes has not seen a declining population yet, but neither has it seen a structural influx from within the region. In this light, it seems that with the Goese Schans – and the other five housing projects – is trying to counter this shrinking tendency. However, this may make things only worse.

What Will Happen?

Unquestionably, the Goese Schans is a beautiful project where aesthetics meet a welcoming urban environment in combination with one feature where Zeeland is known for: its water. However, looking at neighbourhood, city and regional scale, the housing project seems to be unfeasible. The project has been too naively operated and is now a loss in financial terms.

But the financial burden for the municipality is perhaps not the worst thing. What is perhaps more tragic is the fact that there are already 39 houses build, where the pioneering people live on a plot which is supposed to be build upon, but is scrupulously empty. These people bought a house in an imagined vibrant urban neighbourhood, which turned out to be a little suburban project. These people wait, until the building starts again. When this will be however, is uncertain. In this light, it becomes ironic that one of the streets that is finished, is named Wachthuisstraat (literally, guardhouse street). These people are the guardians of the project, looking into an uncertain future, but with a great open view.