On a damp and cold winter’s evening in Portland, Oregon, the best neighborhood to find Instagram-obsessed YUP’s (young urban professionals), hipsters and creative misfits is the Pearl District on the northwest side of the city. The Pearl District has become affectionately known for its plethora of artisan cafes, more microbreweries to explore than Friday evenings in a lifetime and its exceptionally creative art scene. But the Pearl District hasn’t always been viewed as Portland’s cultural and intellectual hub. Just 30 years ago the Pearl District was the most dilapidated, bleak neighborhood in the city; an abandoned industrial neighborhood inhabited by the homeless, seemingly forgotten by the rest of the city. The Pearl District’s remarkable raise from a forgotten, ugly stain on the city’s image to one of the most recognizable neighborhoods in the Pacific Northwest did happen by accident. The neighborhood’s expedient transformation is the direct result of several urban policies that promoted rapid gentrification. The visionary city planners and entrepreneurs who envisioned the Pearl District’s transformation and brought about new found wealth forgot about one aspect of the project—the poor who were displaced.

Jamison Square- A centerpiece of the Pearl District’s gentrification

plan. Photo by Westin Portland

When the Pearl District was first planned in the end of 18th century, it was designed to be a neighborhood that would house the city’s blue collar workers. Portland was a booming economic power in the Pacific Northwest around the turn of the century, with it economy fueled by the burgeoning timber industry. European migrant workers flocked to

Portland where jobs were plentiful.

Like all expanding cities, Portland experienced a housing shortage and the Couch-Addition was the city’s solution. The Pearl District was part of the project and was designed as a neighborhood to house many of the lower-middle class migrants working in the lumber yards. The Pearl District was an ideal location for this type of housing because it was located adjacent to Portland’s rail yard, a major economic hub in the region. Portland was an agglomeration point for the timber industry and the rail yard was one of the largest exporters of lumber in the region.

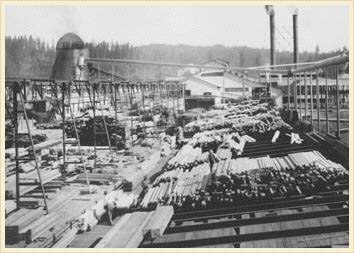

Portland’s largest lumber mill- 1903. Photo by Portland Lumber

Association

By the early 20th century the timber industry and bustling rail yard in Portland were in steep decline. The blue collar workers that were living in the Pearl District began leaving the neighborhood in search of new opportunities. In their wake, furniture craftsman began moving into the Pearl District, changing the fabric neighborhood from residential to industrial/commercial. The newly-invented Pearl District thrived for nearly 50 years until a recession struck in the late 1960s, crippling the US economy.

The late ‘60s and ‘70s marked an era in which the Pearl District was a forgotten part of the city. The once vibrant neighborhood had become a shadowy skeleton of its former self. Portland’s homeless flocked to inhabit the abandoned buildings and warehouses. The Pearl District is a small neighborhood of only 1.2 square kilometers but the City of Portland estimated that there were an astonishing 2,000-3,000 homeless people living in the neighborhood during this period of downturn. In part due to low real estate cost, developers began punching land and slowly redeveloping in The Pearl District throughout the 1980s. 1994 marked a year for the Pearl District in which rapid gentrification truly took its form, Portland planners published their River District Development Plan, an urban renewal project centered around gentrifying northwest Portland, most substantially the Pearl District.

As public redevelopment funds and tax breaks took affect, developers transformed the Pearl District from a dense neighborhood of crumbing lofts and dilapidated warehouses into modern apartments, elegant townhouses and sophisticated storefronts. Families and YUPies began moving in, forcing the homeless deeper into the periphery of Portland. Hipsters quickly opened artisanal microbreweries and fair-trade, gourmet cafes which raised rents, forcing out small shops and markets that had been fixtures in the Pearl District’s age of downturn. Over the course of fifteen years the Pearl District redefined itself from a neighborhood riddled with crime and the city’s largest homeless population to a neighborhood filled with vitality, innovation and promise. The Pearl District is now home to Portland’s most acclaimed restaurants, renown cultural venues, and is the most desirable place to live in the city. The neighborhood is a classic example of successful gentrification from an urban planner’s perspective but for Portland’s poor, the Pearl District is a reminder of their repeated disenfranchisement.

During the decade of downturn in the Pearl District, the late 1960s and 1970s, warehouses and commercial spaces were largely owned by banks and lenders. They were foreclosed upon when the furniture industry had a fortuitous collapse during the short stent of economic recession. Many of those foreclosed and vacant buildings were rented out at the lowest rates in all of Portland which is what originally brought in so many poor. Portland has always had a social housing gap and the cheap rents in the Pearl District helped to alleviate the issue. During this period, vacant buildings that weren’t rent out were inhabited by the homeless. There was no better place in the city for the homeless because of the Pearl District’s proximity to the central business district yet sense of isolation as an economically depressed neighborhood.

When the River Front Development Plan went into effect bringing a restored vision to the neighborhood, investors, developers and entrepreneurs began buying as much real estate as they could. As the redevelopment plan desired, all of the neighborhood’s poor began getting priced out. Surely, Portland’s urban planners knew the River Front Development Plan would force out the poor, completely reimagining the fabric of the community but there was no relocation plan in place for those unlucky 2,000-3,000 people who were displaced.

Homelessness in Portland today. Photo by Vice News

Today there are no signs of those who lived in the Pearl District during the late 60s and ‘70s. Many of those who lived in the Pearl District now live in neighboring cities like Gresham, Camas, Troutdale or Sandy, as no social housing units were constructed in the newly-vibrant neighborhood. For those who were displaced, the Pearl District isn’t symbolic of a successful gentrification project. Rather, its a reminder of the dark side of urban development.

Its the moral imperative of urban planners to not just think of gentrification as a tool to transform bleak, marginalized neighborhoods into prosperous spaces through institutionally legitimized displacement. Gentrification also needs to have a focus on how displaced communities will be fairly and equitably relocated. Gentrification is an urban process that occurs in countless cities across the globe but far too many cases, urban planners neglect to think of their city’s most vulnerable and that is a practice that must be changed.