In March 14th’s post we learned about Newcastle’s lack of proper cycling infrastructure, cyclists’ minority position on the roads and the dawning of a brighter cycling future. I couldn’t agree more with having to forge your routes and tensions with other road users having lived there for nearly two years now. It’s striking Dutch people seem to have a uniform response to such cities by finding oneself on a slightly-more-sporty-than-usual bicycle, biting the bullet of the lack of cycling provision, and wondering how on earth this came to be (also expressed by this tweet

I went to #Newcastle England. The infrastructure and some urban

environments are not friendly. #Cycling is a crime! pic.twitter.com/KMIi21QGCs— Urban Cycling Living (@projectsfromNL) 8. Juli 2016

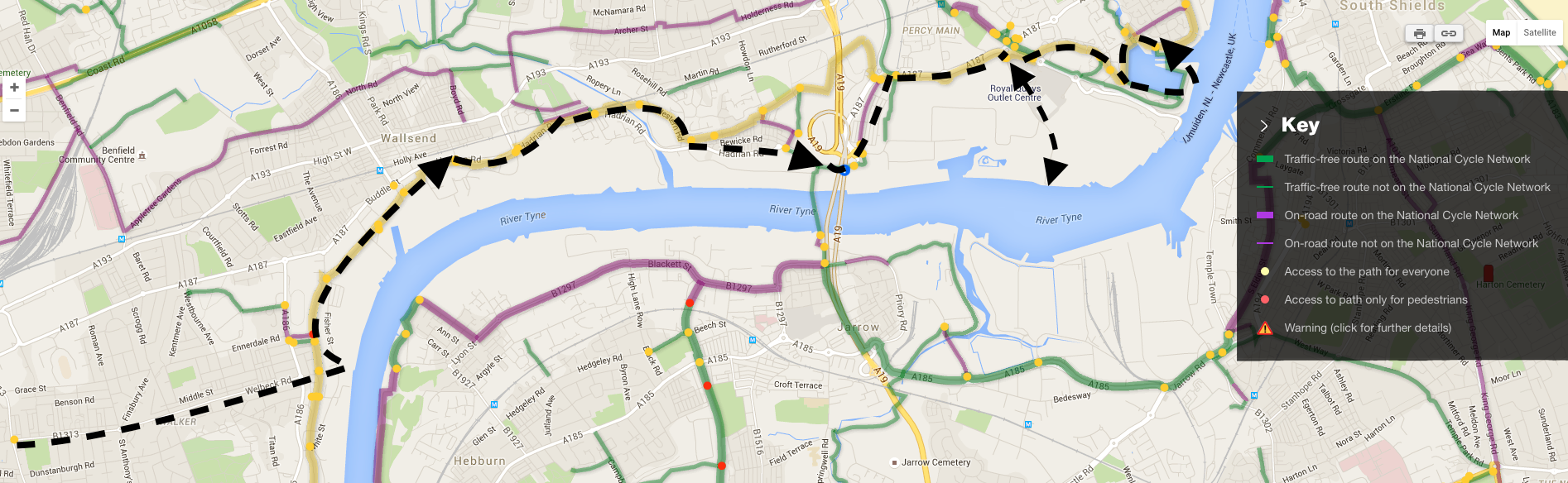

It’s no surprise Newcastle’s city centre isn’t the only place with this precarious situation – no place in the Northeast of England has particularly good cycling provision. What is provided for though is leisure cycling, with the Tyne & Wear region hosting 147 longer-distance cycle routes. Every weekend these routes bring hundreds of smooth-legged men whizzing along disused railway tracks or woodland paths. It gets interesting though when cycling is turned into a means to an end rather than an end in itself. What happens if you use these routes to actually get to a place you need to be?

Hadrian’s Cycle Route

On a rare sunny evening I decided to leave my Dutch (utility) cycling pattern for a moment – I usually cycle to commute, shop and meet people – for a more leisurely ride. I was intent to find a nice view over the Tyne River, something you wouldn’t expect to be too difficult in an area called Tyneside. To my delight I found a suitable route called Hadrian’s Cycleway – could you imagine a Roman emperor really cycled here? – that leads along the river, and would for sure provide access to my ‘destination’. Setting off from my gym in Byker, I must have been in a sporty mood that day, I rode east, passing a few deserted industrial estates, before finding the road that would lead to the cycle route. It basically borders the river on its left bank, but a big blue fence blocks any sort of view. Well, I only just started so I was sure riding some miles downstream would do the job.

Industrial Parks along the cycle path (by Wilbert den Hoed)

The cycle route proved to be a nice path, a bit narrow perhaps but smooth and off the main road for a mile or so. Still no Tyne sight though, looking to the right mainly offered views on grim access ways of industrial parks, big fences, or a hedge at its best. Then the path merged onto the main road again, and my view-plans were shelved. The shared footpath took me along Hadrian’s Road, with a couple of miles of uncomfortable hopping on and off the curbs of exit roads. Cycleway 72 then starts to make me feel even more of an outlaw when having to cross the A-road to avoid riding straight into the Tyne Tunnel access road. Sadly, the only way forward was inland and I started to worry if I was ever going to reach my not-too-specific-destination before finding myself on the seaside. Approaching the quays of the Newcastle-Amsterdam ferry I tried my luck and turned right onto a random road towards the riverside. Again, my hopes for a calm sit-down were dashed by a subtle sign I wasn’t welcome here (image 3) and had to make my way back uphill – about one kilometre and several calories wasted there.

More Industrial Parks (by Wilbert den Hoed)

I put my last hopes on the picturesque harbour of North Shields. Cycleway 72 led me there on not too comfortable shared paths on the side of the A-road, but it has to be said, the view was there. Just a little bench would make me a perfectly relaxed evening sunbather. Oh wait, none of that (image 4). I’m not sure, but isn’t it strange a 7-mile stretch down a river doesn’t offer you a view of it, let alone a place to sit down? Especially in an urban area, with large residential areas all along the river from where I set off.

Finally, a View of the River from the Cycle Path (by Wilbert den Hoed)

Forgive me the sidestep from cycling, but it is clear that private industrial space has won it from ‘the local’ here, from the right for mobility, and ultimately quality of life. When reaching a pleasant place like the North Shields harbour all space appears to be private and I should consider myself lucky I’m allowed to trespass the harbour’s premises. This may be more of an issue of public-private tension or urban design, but the lacking ability of infrastructure to bring you somewhere certainly raises questions. If you cycle to reach a destination (and not just for the sake of cycling) you can’t assume a route actually gets you there.

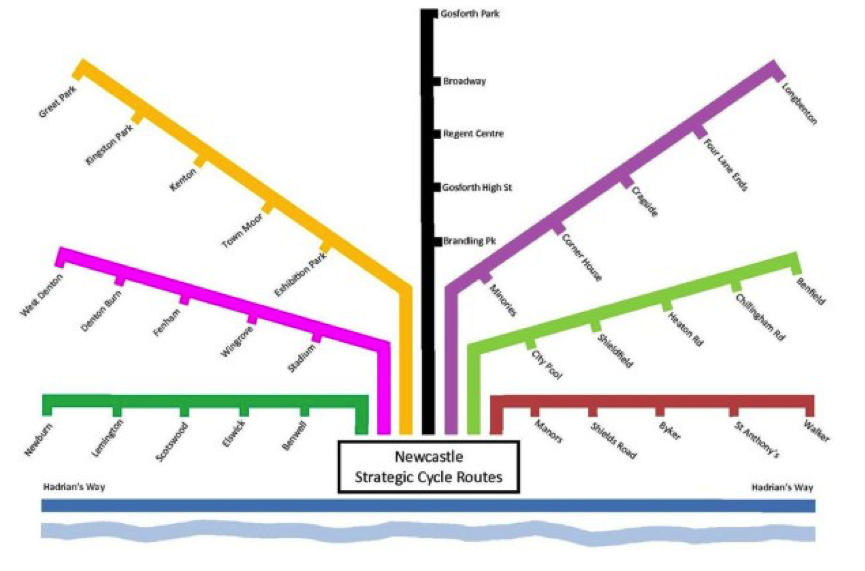

Disconnection from the immediate surroundings isn’t something that really matches the experiential nature of cycling. Even dedicated cycle networks seem to do that though, at least so does Cycleway 72 for a substantial part. Worryingly, also Newcastle’s proposed urban cycle infrastructure plans are designed with a network vision. If the same understanding of a cycle network is used – one happens to be very centralised too, as seen below – the question is if new routes will actually lead somewhere. What happens if we swap the destination of ‘somewhere along the Tyne’ for a friend’s place, a shop or the workplace? Are these allowed to be off the organised, demarcated routes?

Strategic Cycle Routes network (Newcastle City Council – Cycle City Ambition Bid)

For such a network to be usable, a more system-wide approach is needed, linking up its ‘spokes’ and reaching into the fine-grained nature of everyday activity. In the case of Cycleway 72 the backyards to connect to are never far away. As I’m heading back home I realise an hour’s ride learned me a lot about the ability of commercial parties to change the landscape.. Cycling-wise the ride back offered me some new challenges ranging from crossing motorway exits to manoeuvring through the tight high street of Wallsend. Lots of work to do there, but let’s make sure we don’t apply the wrong principles to a right change.