Let’s close our eyes and imagine. It would be quite extraordinary when 18.000 cyclists would take over the Autobahn in the direction of Frankfurt am Main to protest the most important industry of the country: the car industry. And yet, it happened (for footage see Hessenschau). On the 14th of September 2019 pedestrians, cyclists and public transport commuters took to the streets of Frankfurt and set a sign for their beloved future: a future in which there is more space for pedestrians, safe cycling routes, and public transport. And yes, consequently less space for cars.

Why Protest?

The reasons for protesting are evident (by no means exhaustive): The German car companies were the protagonists in the diesel scandal, while politics have been reluctant to react in an adequate way to show the people that illegal behavior, no matter how prominent and influential your company is, does have consequences. In light of climate change, the traffic sector is the only German sector which hasn’t reduced its CO2 emissions in the last decades, leading to the risk of driving bans. The news that the Deutsche Bahn, dealing with austerity, couldn’t live up to their standard: out of all the ICE trains running through the country, half of them showed some kind of defect, and on average 30 percent were showing delays. Not helping either is the growing number of SUVs on the streets, on the one hand instigating discussions of their questionable use in scarce urban space, while others argue for widening(!) the car parking spots. And among others, a tragic fatal accident in Berlin, in which four pedestrians were killed after a car driver couldn’t control his SUV.

Car centric planning

All these things combined made the 14th of September, at the doorstep of the IAA (the international car industry exhibition), a remarkable and important day. It becomes more and more evident, the car-centric planning approach is a dead end and causes more problems than it resolves. Only making cars electric will not change enough in this equation. A holistic view of urban mobility planning is asked for in which city-dwellers prefer the bike or public transport to get through the city and commuters don’t take their car to get into town. As a Dutchman and urban planner, it feels totally absurd to see so many car-commuters every morning standing in line on the large Mainzer Landstrasse only 200 meters away from the Frankfurt Hauptbahnhof. It is for me a clear sign, Frankfurt needs to do more and do things quicker than they have done in the last ten years.

Change on its way?

And it seems, whether or not reluctantly, cities are on their way to change the status quo. By the consistent and inexhaustible energy of the Frankfurter Radentscheid, local Frankfurter politics turned around and recognized that Frankfurt has to really do more to change and get the urban mobility forward by, among others, reserving space for cyclists.

Whereas the car-centric city has been implemented out of a strong ideology of individualism, technocratic beliefs and business interests, the Verkehrswende which scholars and grassroots groups now argue for is, apart from the humanistic perspective, also based in empiricism. A street with trams, buses, cycling lanes and wide pedestrianized areas can schlichtweg carry more people than one with car lanes. And equally important: like adults, children can use the streets safely.

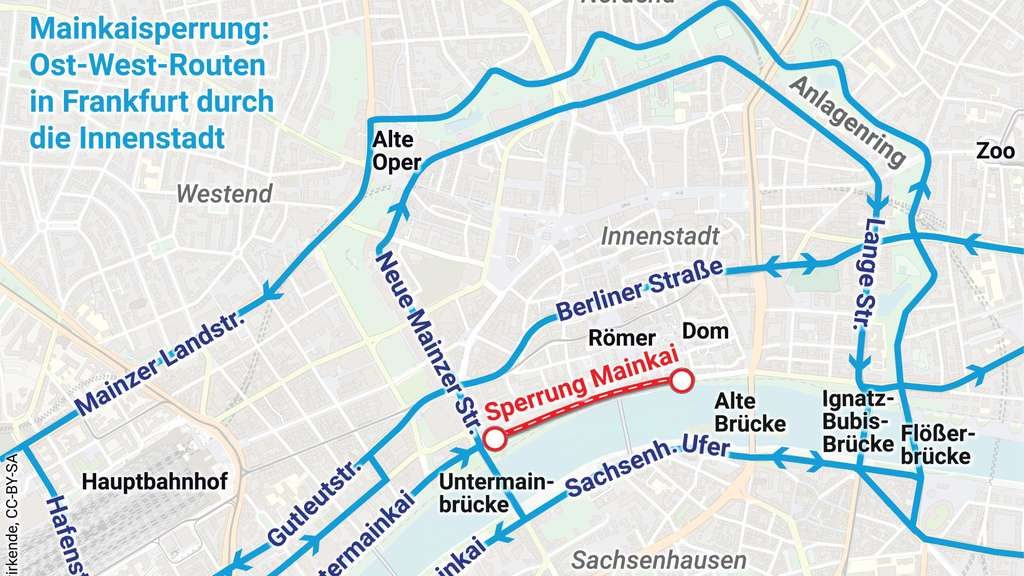

Opening a street for cyclists and pedestrians

Cities such as Frankfurt have a long way to go. The privilege of cars is visible on every road, on every sidewalk and through every move you make in the city. The city breathes car – perhaps even literally. You can feel it, even on the Mainkai. This is a car boulevard on the northern side of the river Main which is now open for pedestrians and cyclists and blocked for cars. Here you can get the cyclist experience one might have in Dutch cities: a relaxed feeling which lets you overthink life, decisions, and conversations you might have had the day before. This is a rare experience in Frankfurt, considering you are usually busy with not getting hit by a car. For pedestrians, however, it is a rather strange feeling to walk on the Mainkai. Whereas the water and the trees on the pedestrianized boulevard make you feel at ease and welcomed, the street (only 15 meters away) itself shows other qualities: dark asphalt, long stretching linear lines, no small structures, no trees. One thing is clear: You shouldn’t be here. Traffic architecture influences how you experience this particular environment. The logic of the urban space is based on a technical and not on a human scale.

Considering there are civic groups and an Ortsbeirat arguing now to quickly end the “opening” of the stretch for cars again, the city might do well by implementing infrastructure which invites people to use the street as a plaza (example Brussels). Make sure there are places to sit, to play table tennis or football and let children or whoever feels like it, paint the street. A few food trucks would perhaps help to shape the boulevard character. In other words, it is important to accompany a solely technical improvement with sociocultural and aesthetic measurements. Opening a street for pedestrians and cyclists is one thing, making it a loveable area, accepted by most, is another.

Things change, slowly but surely

All in all, the agreement with the Frankfurter Radentscheid and the opening of the Mainkai are positive signs for a city in transition. Nevertheless, given the protests, one cannot escape the feeling this transition is still very fragile. This is undoubtedly due to the fact Frankfurt has not yet embraced the transition on a wide political spectrum and has thus far been reactive rather than proactive. Even though it is a welcoming sign citizens are making themselves heard and policies are implemented, it is essential, however, that politics are consistent in pushing for the urban mobility transition, communicate that and start to understand, that urban mobility is not only a technical traffic engineering issue but also a sociocultural change. Consequently, along with the technical measurements, sociocultural policies have to be introduced. Only in such a way, Frankfurt residents will start to understand that it is not just the wet dream of a few activists to make Frankfurt’s urban mobility ready for the next decades to come, but a sheer necessity. For 65 years, Frankfurt has tried its best to solve urban mobility through car-centric planning; up to a point diesel cars could even be banned. It seems fair to say, it is now time to try another route. One thing is clear, on the 14th of September, the Autobahn itself was undoubtedly surprised by how many people it could carry in such a compact space.