We are off on another adventure in our Frankfurt Urban Development series. After discussing the cycling infrastructure, car centered streets and the car saturated inner city, we now pick up the tracks exactly where we halted: the Berliner Straβe.

Car still the status symbol?

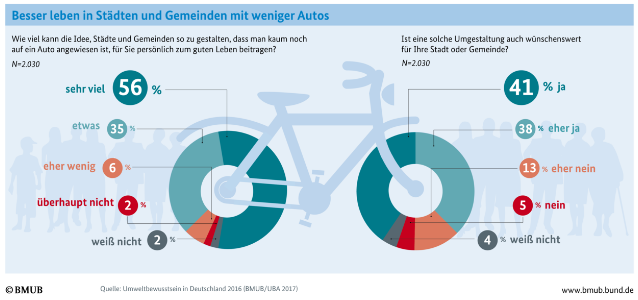

As said, Frankfurt is a perfect example of how post-war urban planning has dramatically changed the morphology of the city: Asphalt boulevards, wide highways and good motor vehicle accessibility at the expense of public transport, cyclists and pedestrians. But as times change, so do personal preferences and sociocultural perspectives. Whereas the car was thé status symbol of the 20th century, this seems to steadily decline in the 21st. Alongside increasing urbanisation levels, scandals on the part of the large German car companies (diesel scandal, cartelisation, human emission tests), make that for a larger part of the German society, the car itself has become a point of discussion. As the latest study of the Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit shows, 79(!) percent of the respondents are in favour of planning their cities and towns in order for them to be less dependent on the car. Even though, this doesn’t say much about the actual individual behavior, it does say something about how the car is viewed: not as the single most important mode of mobility, but rather just as a part of it.

Umweltbewusstseinsstudie 2016 (Source: BMU 2017)

Das Innenstadtkonzept

In line with a less car dependent planning, the Planungsamt in Frankfurt has developed an integrative vision of the Inner City in the Innenstadtkonzept (inner city concept). Published in 2015, it shows how the city of Frankfurt wants to change its car saturated inner-city and make it more welcoming to pedestrians and cyclists. Rather than “planning for movement”, the focus is on “planning for staying”. The main goal is to shape the city centre as a space where people meet, live and work and give meaning to the city. Some of the main points are to develop more space for living and working, shaping high quality public spaces, catering for mixed-use and strengthen the connectedness between the city and the river Main. And exactly that last point is of particular interest, as in this regard the Berliner Straβe plays a vital role.

The Berliner Straβe

Berliner Straße in richtung Westen (source: Daviidos)

In the Innenstadtkonzept the Berliner Straβe is considered as a barrier between the walkable part of the city centre (the shopping area of the Zeil) and the river Main. The four-lane throughway is built after the devastating Second World War, and replaced the formerly much narrower Schnurgasse. The Berliner Straβe became a striking epitomisation of the by then overwhelmingly supported vision of the ‘autogerechte Stadt’ (City for Cars). Again, planning for individual mobility, in which the car was considered the optimal mode of transport, pushing cyclists and pedestrians to the margins of the street (literally).

Different parts in the city centre to the river Main (source: Planungsamt, 2010) – visualised paths my own

As the map above shows the route from the Zeil to the river Main, the Berliner Straβe, by its design and symbolisation of car centered planning, fragments the city centre dramatically in a northern and southern part. People here are forced to cross the Berliner Straβe highway to get to the old heart of Frankfurt: Römerplatz and the river Main. And not everyone is happy with that, not to the least, the shopowners of the Berliner Straße. They openly advocated for a 30 km/h speed limit and more pedestrians crossings. They realise the street scape is not welcoming to customers.

Changing the Berliner Straβe

Proposed changes to the Berliner Straße – Verkehrsdezernat Frankfurt (2) (source: Planungsamt, 2015)

In order to reduce its fragmenting nature, the Verkehrsdezernat of the city of Frankfurt has proposed to reduce the four-lane highway into two lanes and introduce cycling infrastructure (see illustrations above). These proposals have been skeptically received by the local parties CDU and SPD and the Chamber of Commerce (IHK). They argue that the street will reduce its car accessibility, especially during rush hour traffic. This reaction shows interesting similarities to a planning measure at the Hauptwache in 2009 (where a street became totally blocked from car traffic), in which the same skeptical reaction by local parties (IHK, FDP and CDU) actually didn’t take hold in social reality. The traffic-calm street was realised and Frankfurt can currently enjoy its public space (see here for a streetview. Nevertheless, due to the current reaction to the Berliner Straße proposal, the Verkehrsdezernat conducted another study in which it convincingly showed, that the effects of the lane-reduction would be minimal – if not neglible (see below for visual simulations). As this all happened in 2015/2016, still nothing has been changed. The Berliner Straβe is still highly influencing the fragmented and car centered look and feel of the Frankfurter Innenstadt.

Really change the Berliner Straβe – three scenarios

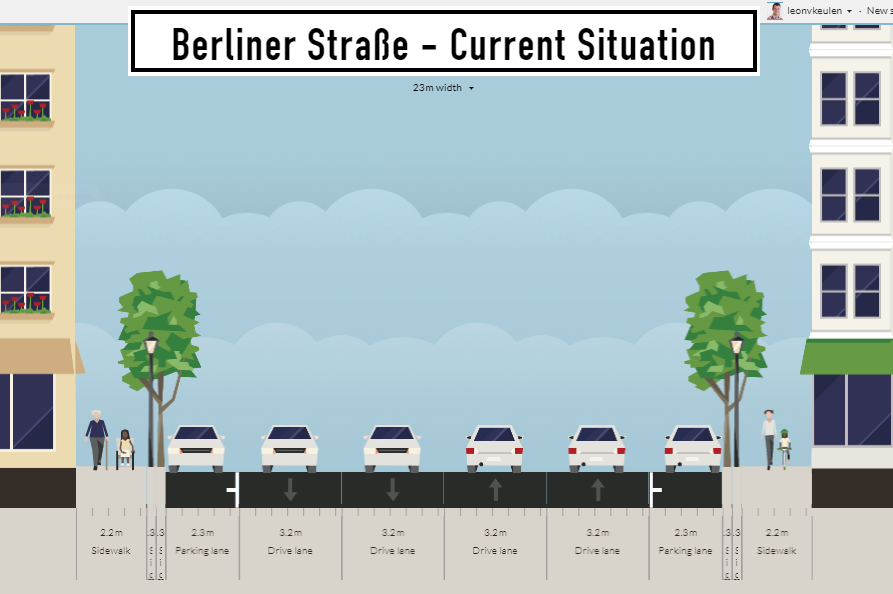

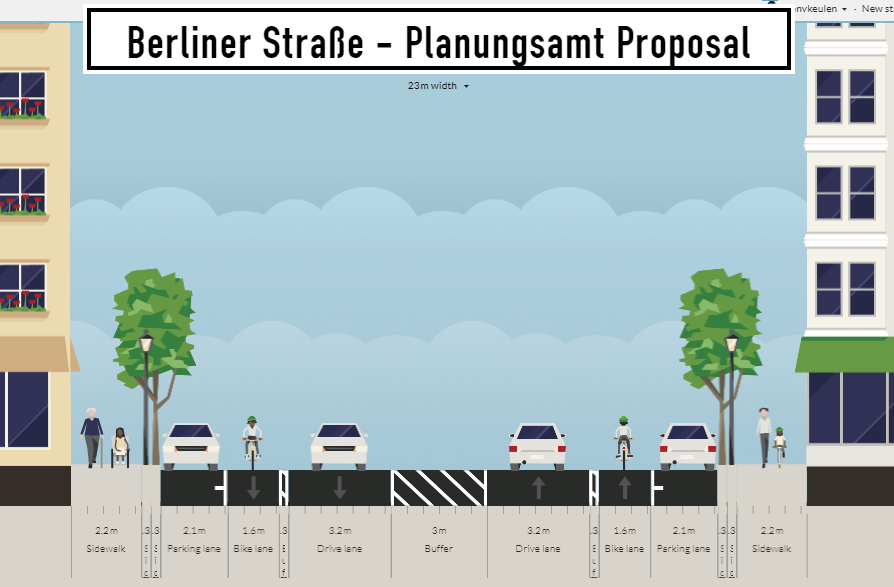

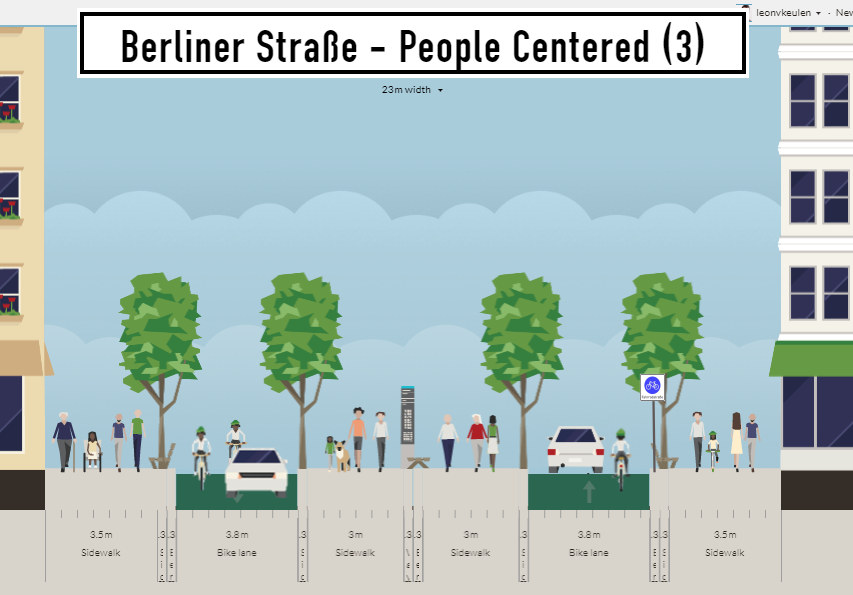

But what did the Planungsamt really propose? As to come loose from the beautiful visualisations, I present here the more technical 2D illustration juxta positioned to the current status of the throughway (the exact measures might be slightly off, as I couldn’t acquire the exact information on the width of the road).

As can be seen, the only real changes that the Planungsamt suggests are the reduction of four to two lanes and the introduction of the cycling lane. The middle buffer zone is either usable for cars in both directions (in case a parked car blocks the road) or can be used by pedestrians (who want to cross wherever they want). The width of the sidewalks will be kept in the same conditions as they are now. Even though a great step forward, there are some deficits from a city planning perspective. One of them obviously being the fact that there will still be a lot of asphalt, a lot of car, whereas pedestrians and cyclists still have a marginal part in the street design. Especially the cycling lane situated in between a moving and a parked car makes cyclists susceptible to stress and ‘dooring’. Besides, the width of the sidewalk still minimizes the opportunity for local stores on the street to open up, built terraces and interact with their customers and the city itself. The street will still be designed for movement, even though it is situated in the heart of Frankfurt with the potential for shop owners and pedestrians to make it a livable, walkable and an engaging street, where people like “to be” rather than “go through”.

In the following three scenarios I have tried to visualise the Berliner Straβe in a way that it comes closer to the potential the street has. With more space for cyclists and pedestrians, and therefore more space for shop owners to actively invite customers.

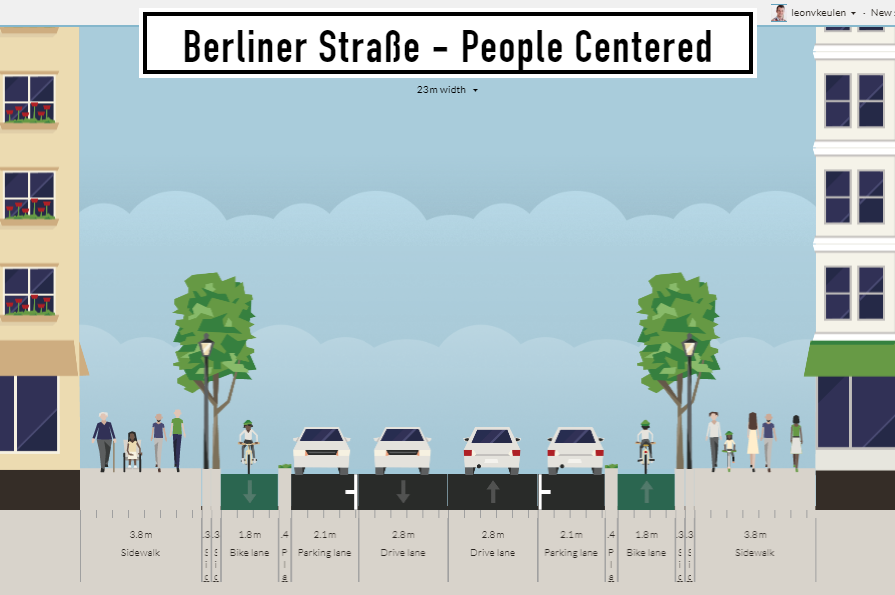

Scenario #1:

In the first scenario, improvements are made for cyclists, pedestrians and car drivers. The width of the sidewalk is almost doubled for real walkability. The separated cycling lane is introduced in order to lower stress levels and protect them from being ‘doored’. The car lanes are slightly narrowed in order to naturally calm the traffic to the pace (30 km/h) that should be allowed. Space is reserved on the sides for parking. I would say: a win-win-win situation.

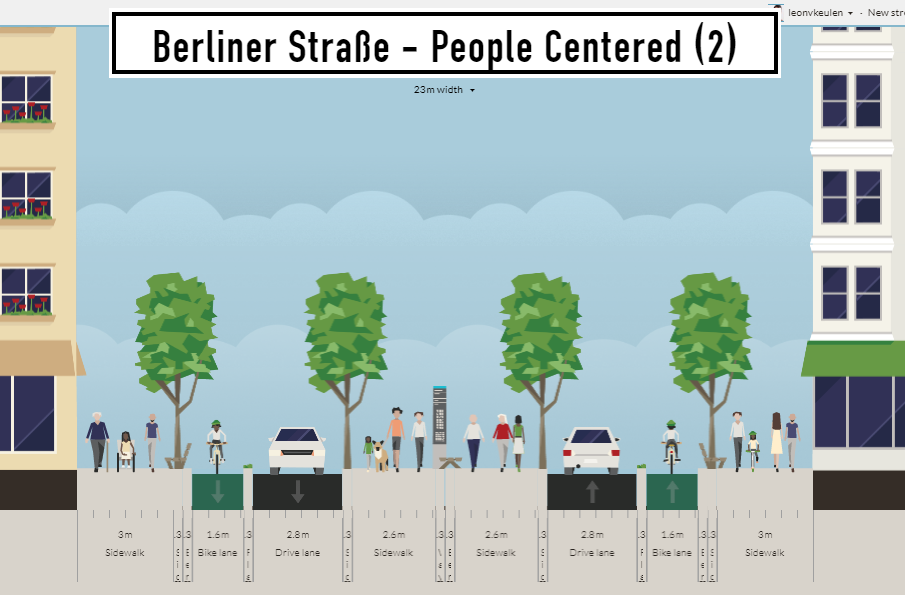

Scenario #2:

The second scenario takes the steps above a bit further. As has been shown in the former blog-post, there is a high supply of parking garages in the city centre, reducing the actual need of parking lots on the streets. Hence, taking away these spots makes for more space to walk and stroll. The cycling lane and car lane are still separated. The only difference is that in both ways, a one-way street is created. In effect, the pedestrian becomes the focal point of the street, leaving them less marginalized and showing the cyclists and cars that they are guests in this street. The disadvantage here is that, due to a one-way design, the pace with which cars go through the street might increase. Hence, traffic calming design is vital in this scenario.

Scenario #3:

The third scenario is perhaps the most people scenario. It doesn’t differ that much from the second scenario, only that the car and cyclists have to share space now. Traffic calming through shared space is in planning practice still under discussion. Nevertheless Dutch cities’ have shown that the ‘cycling street’ in which the motor vehicle is a ‘guest’ can really calm the traffic and can have a positive influence on the quality of public space.

Well, as you can see, much is possible when it comes to street design and planning for people. In the process of the Berliner Straβe, it seems to be a long shot. The SPD, namely, seemed to lobby successfully for closing another street for cars: Mainkai. In itself a great measure to defragmentise the city centre and making the city a more livable area. But simultaneously a missed opportunity to do something about the core of the city in which the Berliner Straße plays a big role. Important in the end is to make a city more sustainable, more enjoyable and, through our street design, more inclusive by showing that the city prioritises the ones that are the most vulnerable in public space: cyclists, pedestrians, children and the disabled.