SPACE VS.  PLACE

PLACE

Temporary, disruptive sustainability projects are criticized for its perceived role as a driver of gentrification, and we are interested in exploring the impact and change projects like De Kaskantine and Mediamatic have upon their surrounding areas.

In our research on urban transformation, we reflected on both the physical infrastructure (or space), and its meaningfulness and appropriation (what makes it become place). These elements are fundamental for overcoming the urban food system challenges and looking for opportunities through specific projects within urban landscapes. (Hunziker, 2007)

From the growing interests in public space occupation, urban festivals, pop up green initiatives, and other projects that use public space to bring sustainability to the forefront of urban dwellers’ minds, these projects impact cities through temporary appropriation of space and add meaning. This brings us to our second question: Which tools and processes do these initiatives use to create urban places and place identity through temporary spaces? How can food be used as a tool for the urban transformation in contemporary processes? How can it help turn a physical space into a place of belonging? (Gieseking and Mangold)

FOOD IN CITIES

The disturbing numbers of the hungry and undernourished, co-existing with ever increasing rates of obese people, the precariousness of small farmers’ livelihoods, the incessant production of genetically modified and processed food, the 2007-8 food price surge, the 2013 horse meat scandal, various E. Coli contaminations, and many other problems at stake demonstrate that the notions of food security and safety are, rather than our reality, a mere aspiration. Conversely, the commodification of food has had major implications on the environment, putting food production and consumption among one of the most significant causes of environmental change including climate change, water scarcity, the loss of biodiversity or soil degradation (Krishnan, 2003). Environmental change puts, in turn, food security and safety at risk. This vicious circle of food production and consumption proves that the current food system is not sustainable and food remains a cause of both human contentment and misery.

Due to the increasing population growth and urbanization, and the subsequent high concentration of social, economic and political life in the urban areas, cities are progressively recognizing and being recognized for their key role in building sustainable food systems. Cities can be defined as “dense networks of interwoven socio-spatial processes that are simultaneously local and global, human and physical, cultural and organic” (Heynen et al., 2006, p.1). Hence, the social and economic interactions that take place in a city reach to different geographies, and the other way around. This puts a great responsibility on the city in terms of geographical impact and allocation of space and resources.

AMSTERDAM AND THE MIGRANT POPULATION

Amsterdam is a home to a truly diverse population. There are about 431,261 citizens in Amsterdam, 51.7% of which are immigrants of every color and ethnicity, mainly from Morocco (9%), Suriname (7.9%), Turkey (5.1%), and Indonesia (3.1). Having the fastest growing population in the Netherlands, the city stands in front of the challenge of feeding increasingly more people and simultaneously becoming a place for its inhabitants to feel as part of Amsterdam’s urban society and to share the city in their diversity.

Alarmingly, the study “Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities” evaluated Amsterdam as the 8th on its list of 13 European capitals and this segregation is expected to gain in intensity, potentially allowing for the city to become a social unrest hotspot (Marwaha, 2015). In Amsterdam the incomes are shared less equally than in the whole of the Netherlands. In 2008 the Gini coefficient for the Netherlands was 0.29 (1-the highest).

‘Bread is the staff of life’, but over the last ten years, the prices of basic and nutritious food have risen by 40% in contrast to a sharp drop in the price of sweet and fatty foods (Mamadouh& Wageningen, 2016). This may clearly cause the stratum polarization to accelerate. Without intervention in this area, food injustice and inequality is at risk of becoming a self-reinforcing phenomenon. By looking into how local communities can be engaged in and by sustainable food initiatives, we may know how urban food development can promote diversity and oppose segregation.

USING FOOD AS A TOOL FOR SOCIAL CHANGE:

ENGAGEMENT AND CONNECTION

Food sustainability has been an increasingly widespread concept combining food safety and security with socio-economic factors and environmental sustainability. Hence, it demonstrates the interconnectedness of food industry with other industries and policy areas and its impact on the environment, referring to the essential transformation of the relationship between people, food system and the planet (Dijstebloem, 2012). As Becker et al. (1999) pointed out, sustainability is closely related to “supposedly ‘internal’ problems of social structure, such as social justice, gender equality, and political participation” which makes the discipline social at its core (p.4).

Importantly, access to sustainable food does not merely depend on one’s financial means nor does it reflect an individual consumer choice. Instead, it should be studied as “embedded in the complex dynamics of multiple social practices” (Brons and Oosterveer, 2017, p.1). Indeed, local food systems exist within social environments that have specific socio-historical and cultural contexts and are hence imbued with meanings which shape socio-economic forces (Heinen et al., 2007).

Democracy and active citizenship are the best tools for overcoming complex societal problems by “aiming for more equal power relations within public space” (Crivits et al., 2016, p.14). With this in mind, community development regards communities as loci of social change. Communities are characterized by their “synchronicity” and their “capacity to generate a welter of highly public, contradictory commentary” (Dixon, 2015, p.167). Therefore, it is important to enable all citizens to participate in the transformation of urban food spaces into community places.

Disruptive food projects are embodiment of the increasing power of civil society in transforming spaces to places. They prove individuals simultaneously with a sense of belonging to a group and a bigger independence from the corporate food regime that to a grand extent stands behind citizens’ alienation from their immediate surroundings, from city as organism and from food itself (ibid).

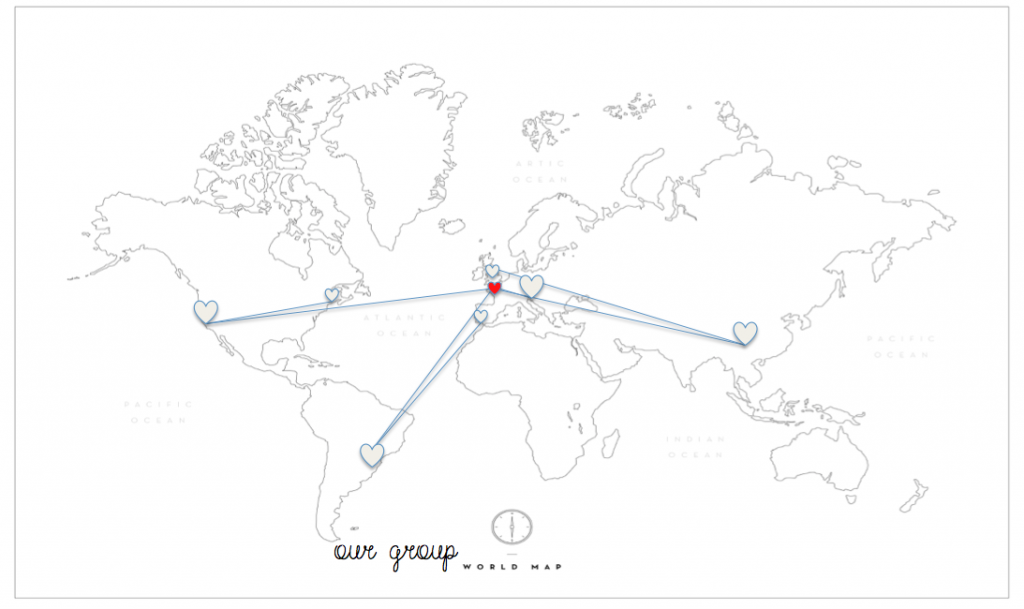

About us:

We made a looong journey to get here. All four of the authors are passionate about food, eating and being together. Different backgrounds (and we are so happy with that), different experiences, always adds something. Like sugar and spice, being diverse makes it so nice 🙂 We really want to understand how food changes more than our own body, and can be a social transformation tool, one that makes cities better, people nicer, life tastier!

Enjoy!

Cat, Mónica, Xuanchen and Zuzana <3