Tourism is a vital part of Rio de Janeiro and Rome’s urban economies. In this blogpost, both cities’ recent city-marketing policies and strategies are being compared. Similarities as well as differences will be highlighted, while it will be assessed to what extent these are related to the city’s locations as well as statuses on the ‘global city’ map.

Seemingly very different cities, Rio de Janeiro and Rome share one very important feature: for both cities, tourism is a crucial economic activity that shapes the cities’ planning and organization. Rome is one of the major tourist destinations in the world, whereas Rio de Janeiro is more of an aspiring tourist destination that experienced major touristic attention while welcoming the visitors of sports mega-events: the 2007 Pan American Games, 2014 FIFA World Cup and 2016 Summer Olympics. Football have been important for the crystallization of Brazilian identity, and Rio, with its stadiums of four major Brazilian football clubs and the legendary Maracanã stadium that hosted two football world cup finals (in 1950 and 2014), is undoubtedly the heart of it. Rome is also a capital of culture, even though ‘culture’ can be characterized differently in the case of these two cities. The Eternal City is known for the preservation of its great historical and archaeological heritage, and its urban policy-makers have identified tourism and culture as the most important sectors of urban development.

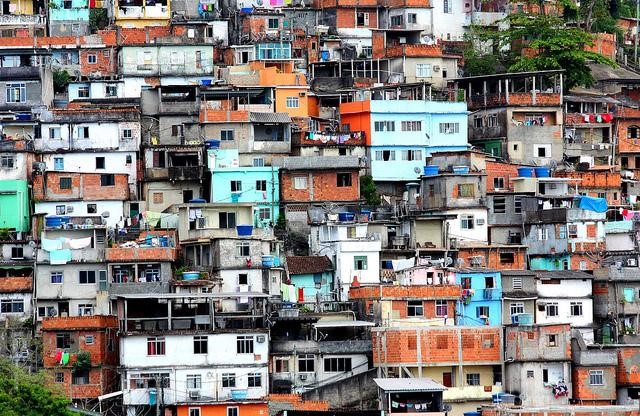

Leaving the status of financial capitals respectively to São Paulo and Milan, both Rio and Rome can be seen as second cities in their countries in this particular regard. Milan is also a competitor to Rome on the tourist arena: according to Mastercard’s Global Destination Cities Index (2018 and 2017), Milan is among the 20 most visited cities in the world, whereas Rome has been knocked out of the top-20 since 2017. Rio, however, is unrivalled as the main tourist destination in Brazil (and one of the top-3 in Latin America), according to Euromonitor International report, but it is still incomparable to Rome in terms of the amount of tourists that it attracts. While Rio used to be Brazil’s capital city for almost 200 years (from 1763 to 1960), it lost this status to Brasilia, and as a consequence it has attracted less public investment in recent decades as compared to when it was the capital . In the 1980s Rio experienced severe economic decline and lost many headquarters of big companies to São Paulo. In the same period income inequalities increased, and currently the socio-spatial inequality and class stratification are very prominent in Rio. The elephant in the room of Rio’s residential geography is the spread of slums, also known as favelas. Every 6th person in Rio lives in one of the more than 750 favelas, the oldest of them being Morro da Providência which is almost 120 years old.

So, these two tourist-oriented cities both need to compete with nearby cities that are more central nodes within the global urban network, but they do so in very different contexts and with dissimilar conditions: Rome is starting to lose the competition in attracting tourists to its more economically active neighbor, whereas Rio manages to maintain its status as a major tourist destination in the country. On the global scale, however, its popularity as a tourist destination cannot be compared to Rome (Rio closes the top 100 of most popular tourist destinations while Rome is in the top-20, according to Euromonitor International report).

Moreover, the ways in which these cities attract tourist are very different: Rome has monetized its historical heritage and symbolic capital of being the Eternal City, whereas the ‘Rio moment’ came along with the opportunity to host several mega-events, and thus to attract global attention and investment. Global institutions like FIFA have high demands for the host cities, and preparations for these mega-events require the implementation of ambitious urban policies: for instance, in Rio they included building several stadiums and the renovation of the famous Maracanã stadium (twice, for the 2007 Pan American Games and the Football World Cup), alongside building the cable car system and the Porto Maravilha, Rio’s vast port revitalization project worth 4 billion dollars. It is hard to imagine such drastic infrastructural interventions in the Eternal City of Rome. Considering these differences, how meaningful it is to compare them and what can this comparison tell us?

Beyond compare?

Hosting mega-events requires opening up to foreign capital, for instance on behalf of the exclusive sponsors and other international companies, and for that one needs the support of the government. For example, drinking beer in stadiums is illegal in Brazil, but for the World Cup exceptional legislation was adopted for the benefit of the main FIFA sponsor. Moreover, most activities are situated in a limited number of neighborhoods, mostly upscale, and thus there is a tendency for global capital to be concentrated in certain areas of the city, which can contribute to the already existing spatial polarization and inequality: mega-events in Rio were bound up with gentrification processes, including real estate speculation, evictions and police “pacifications” of the favelas. It does not mean that there are no such processes in Rome: gentrification and real estate speculation were observed in the Eternal City too, connected with the government’s neoliberal and entrepreneurial policies. However, the context of mega-events (and spectacular urbanization needed to prepare for them) in Rio make its case exceptional, especially when it comes to dealing with slums. Slums were disturbing for these neoliberal policies for two reasons: they occupied the space that could be profitable, and they were an image problem. The best example here is the case of Porto Maravilla, the project of port (that used to be the major slave portal of Latin America) revitalization launched in 2009. The idea was to turn the port area, previously mainly inhabited by a disadvantaged population, into a world-class office and residential area, and thus to maximize its tourist potential. Many inhabitants of the port area were hence evicted, but the main issue for the project was the vicinity of Morro da Providência, the city’s oldest slum that used to house many port workers. The idea was to remove many inhabitants and demolish the buildings, which led to evictions without notice and other rights violations, including police brutality, which caused protests and other kinds of resistance. Favelas are the accessible housing in Rio for lower income groups (real estate prices have been going up everywhere except in favelas, and the situation of the real estate market is currently tense), and due to the mega-events (or justified by mega-events) people were evicted, without covering all of them with the replacements of social housing. Major evictions as a part of the preparation for sports mega-events were thus reinforcing socio-spatial polarization and inequality in the city, where these were very significant already.

On the other hand, social and cultural geographer Malte Steinbrink argues that eviction and brutal “pacification” were not the only ways of dealing with “slum problem” in Rio. One of the strategies included turning them into tourist attractions (providing “favela tours” or making a “favela museum” illustrating the history of Morro da Providência) and “beautification” of slums: for example, painting the houses in favelas in bright, infantile colors. This is where similarities with Rome arise, where processes of beautification and artification of something considered marginal were also promoted by local authorities, but with working-class neighborhoods instead of favelas. “Alternative tourism” in Rome includes creating museums in previously industrial spaces and promoting street-art, making marginal places and wastelands more and more mainstream and inevitably gentrifying them. Local authorities enthusiastically took over few industrial buildings (for instance, the Testaccio slaughterhouse was turned into a museum) to promote the idea of seeing the “alternative Rome”. Some of the practices Baudry links to competition with other European metropolises: for example, for the status of Europe’s street-art podium, Rome is trying to catch up with cities like London and Paris in order to subsequently attract more tourists.

This is different from Rio bidding for hosting the Olympics, but it illustrates that there are widespread and rather similar process of cities competing for international tourism and “experiencing touristification”, which are often inextricably linked with gentrification processes. However, it should be argued here that this process has occurred very differently within Rome: for instance, gentrification in the Testaccio neighborhood that was intertwined with its ‘artification’ and tourist attraction apparently did not involve displacement. Many of the original inhabitants stayed there even though the area changed a lot and turned from a working-class area to hip neighborhood.

In both cities, gentrification and “touristification” of marginal spaces on behalf of local authorities takes place, but the ways in which this is being carried out substantially differs between one another. Spectacular urbanization in the context of mega-events in Rio comes along with the clearance of slums with their negative stigmas (as dirty and violent), which makes this case of beautification rather unique, even though ideas for urban renewal projects such as Porto Maravilla were taken from the global North. The brutal processes of gentrification through evictions and police “pacifications” of favelas are the result of the low statuses of the inhabitants of Brazilian favelas. At the same time, these processes are connected with the current political regime of the city, and its relation to perceptions from the global North (as well as international institutions such as the FIFA) which regard slums as being unsafe and undesirable for international tourists or in other ways inappropriate: relocations of these “less advantaged communities” were a part of Rio’s Olympic bid book, and getting rid of them was a part of the eventual preparations for the aforementioned mega-events, as has also been observed elsewhere across the global South. Neoliberal policies are being implemented both in the global North and global South, and elements of gentrification can be observed in almost any city, which makes it a popular category for possible comparisons between cities. However, this brief exploration illustrates that particular local contexts and power relations, in accordance with the global configuration of (symbolic) capital and power, inevitably shape urban processes in cities that we try to compare. Bearing in mind this interaction and its associated inter-scalar dynamics is essential in order not to take certain assumptions automatically for granted.