Kollwitzplatz, Berlin revisited

My first Berlin experience was in October 1989. Only a month before the borders between East and West Berlin would be opened and the Wall would fall, but me and my high school classmates did not yet see that coming – if anyone back then had anticipated this at all! Of course we were aware of ‘glasnost’ in Moscow, East German refugees in Hungary and Czechoslovakia, and increasing pressure on the GDR rulers by increasingly massive citizen protests; the few images of that which reached West-German television, reached us in the Netherlands too. But who could possibly know that radical change was so close already? It was the typical high school Berlin trip as many West European kids must have had it in those years. Most of the time was spent in West Berlin, except for a day trip to East Berlin. Of course we only got to see what the GDR socialist authorities wanted us to see: Unter den Linden, Alexanderplatz, and a few side streets around it, that must have been about it.

Little did I know that only a stone’s throw away from Alexanderplatz, underground resistance of East Berliners was concentrated in a neighbourhood called Prenzlauer Berg. Daniela Dahn, in her book Prenzlauer Berg Tour (first published in a GDR-censored version in 1987; republished in uncensored version in 2001), and Wolfgang Kil in his essay Prenzlauer Berg: Aufstieg und Fall einer Nische (1992), describe Prenzlauer Berg as a different, semi-autonomous ‘niche’ world in which people critical of or opposing against the GDR socialist regime were overrepresented. It had become an area partly beyond government control: as a typically capitalist working class area, it had been left to decay for decades, and it was in a peripheral corner of the city, cut off from West-Berlin by the Wall. If the GDR (and the Wall) would have lasted longer, most of this late 19th century area would probably have been torn down and replaced by prefab socialist towers and blocks. In the northeast of Prenzlauer Berg, the Ernst-Thälmann-Park gives an idea of what all of Prenzlauer Berg could have looked like then. However, the GDR ceased to exist before these redevelopment plans could be started. The residents protesting against these modernization plans welcomed the saving of their area at first, but most of them were probably disappointed to see how their neighbourhood changed character afterwards. As early as 1992, Kil already points at the first signs of losing the ‘niche’ position of Prenzlauer Berg in reunited Berlin and warns for the risks of gentrification and the loss of a unique alternative culture.

A not yet renovated housing block in the Kollwitzplatz area in 1995; most of the neighbourhood must have looked like this before urban renewal and gentrification began in the early 1990s (picture by author, 1995)

Ernst-Thälmann-Park: what Prenzlauer Berg could have looked like after urban renewal ‘GDR-style’ (picture by author, 1996)

In October 1995, I was back in Berlin, this time as an exchange student. I took courses in urban and economic geography and urban sociology at Humboldt University. I combined this with a master thesis research about gentrification in Berlin. Before leaving for Berlin, my thesis supervisor told me: if you want to study emerging gentrification, the Kollwitzplatz is the place to be! Indeed I felt like experiencing an area right in the middle of that process. At the same time, it was only partly gentrification as we know it from the textbooks. It was at that time somewhere in-between state-led and market-led gentrification, and the two seemed to work in opposite ways. I focused in my thesis on the commercial side of gentrification: the changes in the entrepreneurial landscape. Many new companies had popped up recently and even kept popping up during the few months I was doing my fieldwork, while many old companies were disappearing. ‘Traditional’ companies like grocery stores, bakeries, butchers and ‘Eckkneipen’ (‘streetcorner bars’) were giving way to ‘typical gentrification’ phenomena like art galleries, boutique shops, grand cafes and expensive restaurants. That part of the real estate market was already market-led, with commercial rent levels and already aiming at an audience beyond the neighbourhood. Gentrifiers were already living in the area, but not that many yet, so the new companies also aimed at customers from other parts of Berlin and increasingly also at tourists. The Kollwitzplatz area at that time was still subject to Berlin’s ‘cautious urban renewal’ (behutsame Stadterneuerung) regime, which meant renewal should not go at the expense of less wealthy residents. One of the most powerful policy tools to prevent displacement of lower income residents was a maximum rent for dwellings within the urban renewal area. Other influential factors were subsidies for ‘self-help renovation’ by sitting tenants, and relatively strong citizen participation in the planning process of neighbourhood renovation.

One of the first self-help renovation projects, realised by former squatters in the Rykestraße in the early 1990s (picture by author, 1995)

However, a few years after completing my master thesis, the maximum rent for urban renewal areas was abolished, a rapidly increasing share of the housing stock was sold to private investors, and housing prices became much more market-driven. From then on, gentrification really hit Prenzlauer Berg, and particularly the Kollwitzplatz area. This shift from state-led to market-led gentrification was also a logical consequence of Berlin’s fiscal crisis in the late 1990s. In the following years I frequently visited Berlin and each time I was there, I reserved some time to revisit my former thesis fieldwork area. Each time I saw change, and most of the change fit the gentrification frame very well. Most academic literature and media coverage since 1996 also pointed at the transformation from ‘alternative’ to ‘mainstream’, from mixed-income to (upper) middle class, from ‘gentrifying’ to ‘gentrified’… and ‘touristified’. In 2001, Daniela Dahn’s Prenzlauer Berg-Tour was re-published, including a ’15 years after’-chapter, with telling quotes such as: “Meanwhile, what once was a Geheimtip has been socialized worldwide. Travellers leaving Berlin without having a dinner at Kollwitzplatz first, can be blamed for not having been there at all” (translated from German, p. 203). Shortly before, even German chancellor Schröder and US president Clinton were spotted having dinner at the Kollwitzplatz.

Kollwitzstraße 45 in January 1996 (I lived in this house for a few months then)… (picture by author, 1996)

In 2009, I had another chance to update my Prenzlauer Berg knowledge, when I supervised the Urban Studies (UvA) master thesis of Sjoerdje van Heerden about the attractiveness of Prenzlauer Berg for people with creative professions (see also this recent article in the Journal of Urban Affairs). Gentrification and creativity are often linked; starting artists are often among the ‘pioneers’ of gentrification, but once the area is gentrified, we also often find successful artists and creative professionals among the residents, while the ‘pioneers’ may well be among those displaced. Prenzlauer Berg was no exception to that rule, having become a popular home for both many creative people and many creative companies. Still, somehow the theories about ‘what creatives want’ of their residential environment did not really seem to work. ‘Typical creative class’ preferences as people like Richard Florida suggest, like appreciating tolerance, diversity and a rich offer of urban amenities, were appreciated more by people with non-creative professions than by the creatives themselves! While acknowledging the limitations of the small survey sample, we were a bit puzzled by this outcome; was the theory wrong, or were the non-creatives and/or the creatives in our case study a-typical? Well, maybe this goes to show that Prenzlauer Berg is a pretty unique neighbourhood that always has surprises in store for social scientists…

The ‘Backfabrik’, a former bakery, now redeveloped and full of creative companies (Picture by author, 2014)

In October 2014, I was back in the Kollwitzplatz area. Five years after my last visit, I was surprised to find again quite some changes, this time even in those corners of the area that seemed to have been forgotten or passed by until very recently. At the Straßburger Straße, for example, a messy business site with a GDR army history, later hosting small garage and repair companies, was cleared and a Dutch constructing company was working at the complex ‘La Vie’, sold by the developer as a ‘village in the city’. Also along the Schönhauser Allee, Torstraße and Prenzlauer Allee, the thoroughfares bordering the Kollwitzplatz area, it looked like the last few remaining decaying blocks had been renovated or replaced and the last empty spaces had been filled. At the Kastanienallee, one of the few squatted buildings that had long resisted redevelopment pressure was gone. What has been built and renovated in recent years is almost without exception much more expensive than what was there before. Tourism has become one of the most prominent economic sectors in the area, together with retail, gastronomy and creative industries. Meanwhile, gentrification has also spread across a much larger part of Prenzlauer Berg, including also the areas around Helmholtzplatz, Kastanienallee and Pappelallee.

Construction of the ‘La Vie’ complex, at the corner of Straßburger Straße and Saarbrücker Straße (picture by author, 2014)

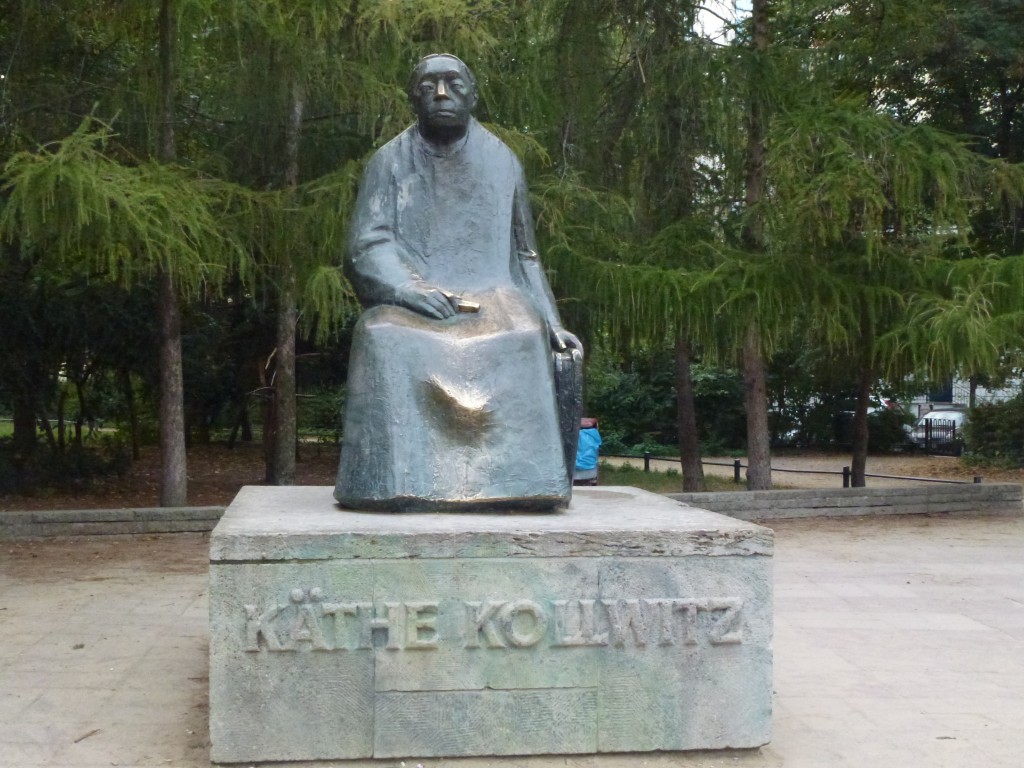

Everything has changed? Almost everything. A few little corners of the area seem to have survived all gentrification, upgrading and development storms. Curiously, this also includes the Ernst-Thälmann-Park, built in 1986 as an exemplary piece of socialist urban design and as an announcement of Prenzlauer Berg’s possible future. In 2014, it became the first socialist prefab complex protected as a monument in Berlin! There have been several redevelopment plans already, but the monumental status seems to have put those plans on hold. At Kollwitzplatz, the statue of Käthe Kollwitz still overlooks the square named after her. Unlike many statues placed in the GDR era (this statue dates back to 1961), this statue has always been beyond any discussion. About 500 m southeast of Kollwitzplatz, one still finds the Metzer Eck, a bar-restaurant that hardly changed its traditional Eckkneipe charm since it opened about 100 years ago. It must be one of the few gastronomists in the area that resisted any adaptation to Prenzlauer Berg’s change from working class to upper middle class area. An even more remarkable gentrification survivor is found between U-Bahnstation Senefelderplatz and the Kollwitzplatz. At the ‘adventurous construction playground’ Kolle 37, local kids have been building their very own wooden ‘castles in the sky’ since 1990. While virtually all pieces of land around it have been redeveloped since then, Kolle 37 remained untouched. To find such a low-threshold public function at possibly one of the most expensive pieces of land in Berlin is somehow comforting: gentrification may change a lot and not always for the better, but it can be resisted.