The building’s exterior, typical of German post-war reconstruction styles, does not reflect what took place behind the non-descript door. There, however, in Mintropstrasse 16, in a somewhat seedy neighbourhood area near the Düsseldorf central railway station , a revolution in music started some four decades ago. In stark contrast to the monumentalised Abbey Road studios in London where The Beatles recorded most of their songs, there is no indication that this was once home to the Kling Klang Studio where Kraftwerk recorded their seminal albums in the 1970s. Techno, house, dance, trance, and also much contemporary R&B: they all owe a debt to these German pioneers of electronic music. Even now, some forty years later, “‘Autobahn’ still sounds like a road map for the musical future” according to Stephen Dalton (2015) in a recent issue of Uncut.

Mintropstrasse 16, picture by author

Not just music

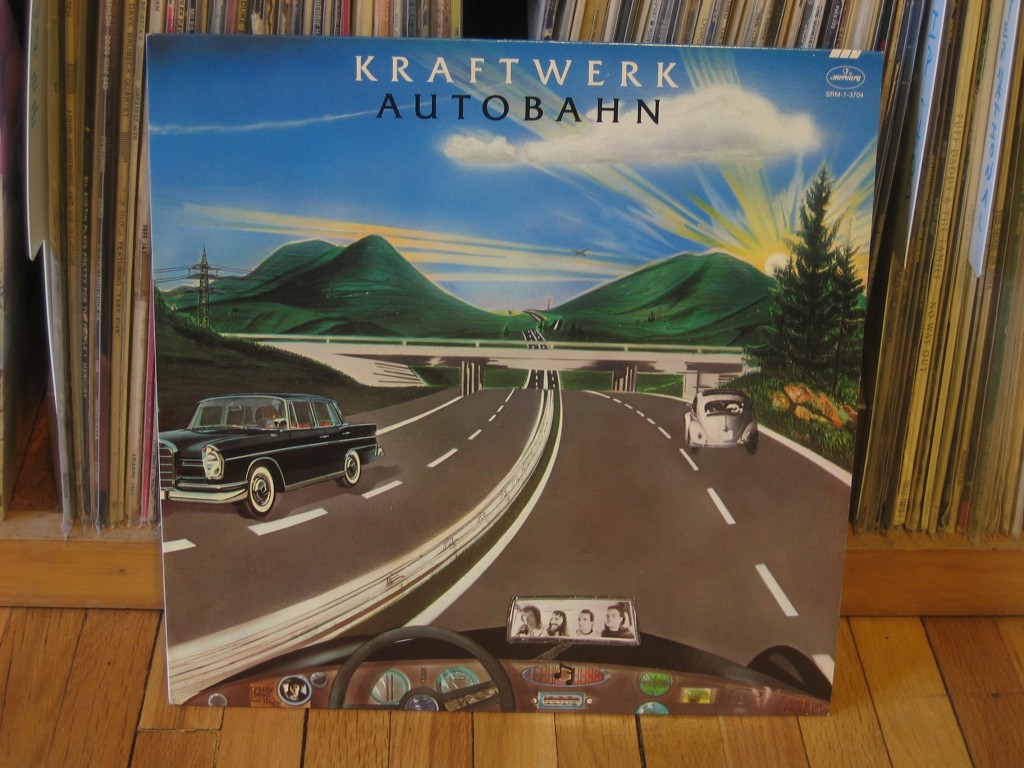

In the early 1970s, Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider, both students at the Robert-Schumann-MusikHochschule in Düsseldorf, decided to create their own kind of music which would not be based on the dominant American or British templates of pop music, returning instead to rather high-brow European sources of inspiration. So no Chuck Berry, Elvis, Dylan, Beatles or Rolling Stones, but instead icons of German music: Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, and, importantly, Karlheinz Stockhausen, who broke new ground by playing Bach on what was then a new instrument, the Moog synthesiser. Following the example of the latter, they opted for a completely electronic instrumentation. In 1974, they scored an international hit with a shortened version of Autobahn, their minimalistic ode of 22 minutes to the iconic German highway. The album cover showed a highly stylised, almost completely empty highway save for one Volkswagen and one Mercedes, both archetypical images of the German Wirtschaftswunder, within an almost mythical mountainous landscape as backdrop. The cover, influenced by Joseph Beuys who taught at the art school in Düsseldorf, made clear from the start that Kraftwerk was not just about music, but aimed at a total work of art or Gesamtkunstwerk of music, imagery, and dress (Buckley, 2012). Later on, with the Man Machine album, when influences from filmmaker Fritz Lang (Metropolis) and Soviet constructivist El Lissitzky, both from the 1920s, were absorbed, nostalgia and the future seamlessly blended.

Autobahn vinyl cover, picture by Bryan Kennedy

With chart success in both the UK and the US, German music now came to be associated more with avant-garde than with the risible schmaltz of the Schlager music. David Bowie, prominent trendsetter and tastemaker in the 1970s, was one of the torchbearers. He was hit by “their singular determination to stand apart from stereotypical American chord sequences and their wholehearted embrace of a European sensibility” (Dalton, 2015: 49). Others, among them former Roxy Music member Brian Eno and the composer of minimal music Philip Glass, were also inspired by Kraftwerk.

European elitism with a huge impact

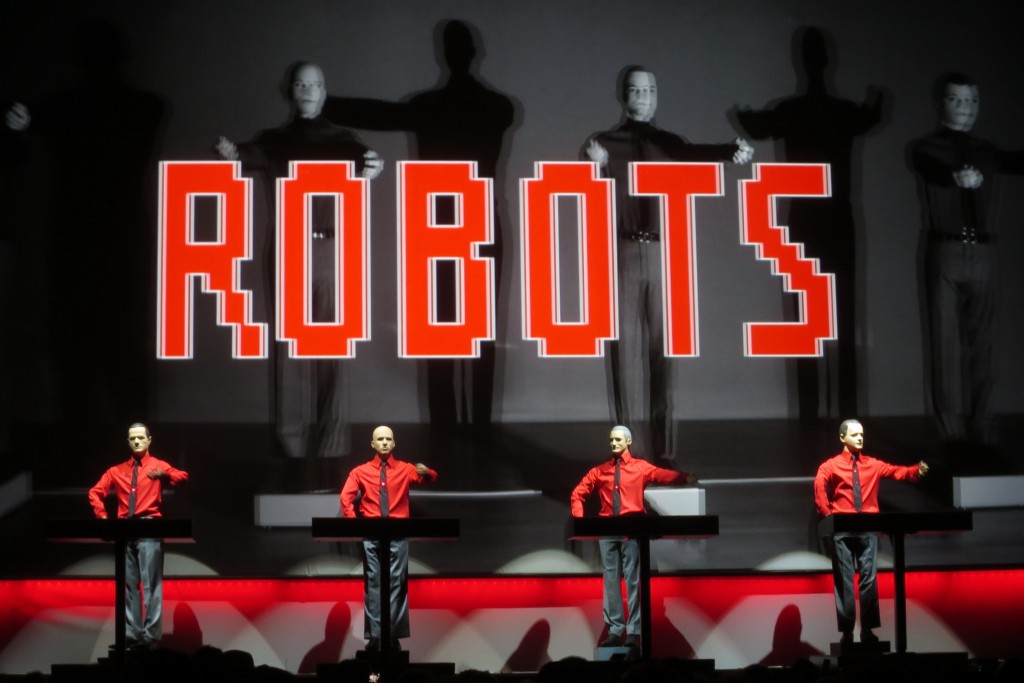

Even more remarkable was the impact of Kraftwerk on the Afro-American music scene. A recent BBC documentary, tells the story about a Kraftwerk concert in Detroit in 1981. On stage, four static and seemingly uncharismatic, robot-like musicians from the (West-)German upper-middle classes performing for a dominantly black audience with a rather different social background dancing to the rhythms of Trans Europe Express and Robots. Ralf Hütter later described the response of the audience as “very strong, very dynamic” (Hooper, 2013). Music and imagery, deeply embedded in an elitist European culture, apparently resonated with the thriving Afro-American music scene in Detroit, the city of Tamla Motown. A DJ prepped the ground for the breakthrough, suitably named Electrifying Mojo, who had a radio show targeting the Afro-American public. He thus embodies the crucial link between Kraftwerk and Techno, the electronic music genre born in Detroit and mother of a whole host of dance music styles.

Kraftwerk performance, picture by author

A temporary music cluster?

One could also argue that Electrifying Mojo can be seen as the embodiment of a so-called global pipeline linking two spatially disparate clusters of music production and thereby contributing to processes of innovation. These clusters themselves are typically spatial concentrations of art worlds (not just artists, but also critics, tastemakers, Kloosterman, 2005) in combination with a dedicated infrastructure of institutions among them and, in the case of music, especially studios (Watson and Ward, 2013). Düsseldorf apparently provided such an environment in the 1970s. One could also argue that its initial relative isolation from other musical centres in combination with its rich cultural legacy was one of the conditions that fostered the creation of highly original new soundscapes and forms of representation. This, however, did not last and Düsseldorf has dropped off the radar as a centre of music innovation of global importance. The city evidently lacks the critical mass and the diversity of global cultural capitals as London, New York, and Los Angeles, which have been able to reproduce their creative milieus over extended periods of time.

There is, however, more than just sheer numbers to sustained creative milieus. A smaller city may specialise in a particular cultural industry and specific style. Such specialisation is fostered by the continued presence of an informed local clientele or, in the case of music, devoted fans helping to infuse the cityscape with meaningful signs referring to that music style. That I had to ask a local resident who happened onto the street if his ‘neighbor’ had indeed been home of the famous Kling Klang Studio goes some way to explain why Düsseldorf has remained a one-hit city wonder.