The remarkable development of the China-Belarus Industrial Park

About a year ago, there was a noteworthy news item in the global media. It was announced that China would invest $5 billion into the development of an entire city in the forests near the Belarusian capital Minsk. The plan included enough housing to accommodate more than 155,000 people, which means that it will enter the top 10 of largest cities in Belarus. The ‘city’, will be designed as an industrial park, after Chinese example, while it is being branded as ‘the modern city on the Eurasian continent.’

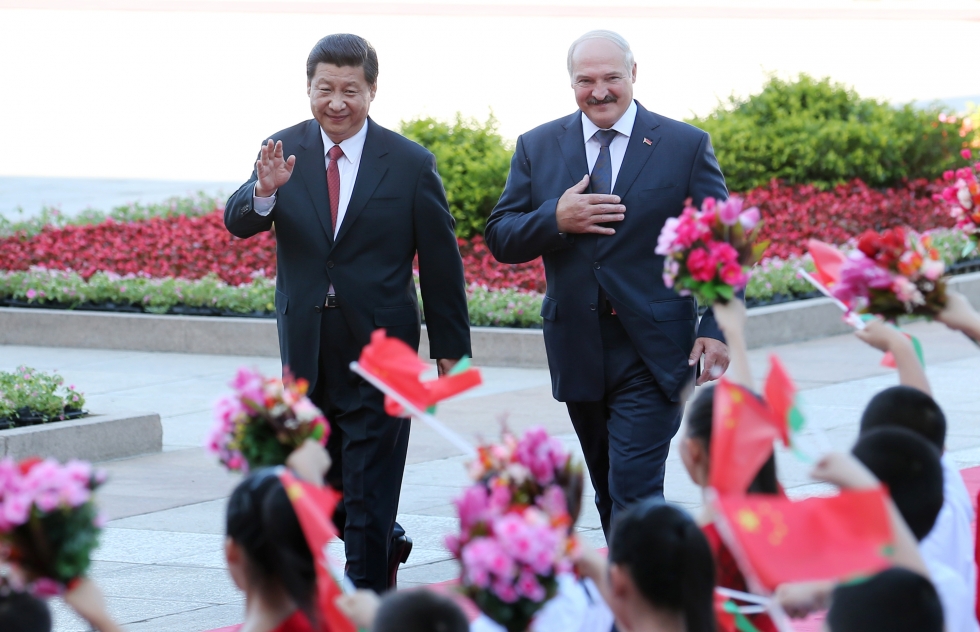

The Presidents Xi Jingping and Alexander Lukashenko during a meeting – picture by Xinhua

According to the original plan, the first stage of the project will be ready in 2020. The second stage will need another 10 years to be completed. In order to attract foreign investors, the park will have some significant tax incentives that are ought to make it attractive for high-tech and export-oriented (foreign) businesses to jump in. This way, Chinese exporters are within the geographic reach of the European Union while having access to a cheap but educated (Belarusian) labour force, in case they will not be bringing their own. At the same time, Belarusian president Lukashenko stated that it will be a ‘technological leap’ for his country. Although it seems that the initial phase of the development has not occurred without a hitch, it was announced recently that the construction is supposed to start this month. It thus looks like Belarus will get another remarkable city, next to its capital Minsk which does not quite seem to fit into any of the common post-socialist urban trajectories.

Industrial Parks: yet another ‘new Silicon Valley’

In 1994, China, in close cooperation with Singapore, started with its development of the ‘Suzhou Industrial Park (SIP),’ just outside Shanghai. This will count as a blueprint for the park that is about to be established in Belarus. According to its own website, SIP is a great success story: In 2006, this area got upgraded with investments in R&D, technology facilities and innovation bases. In this video, it is stressed that the city is a gateway between China and the world, combining eastern and western values in order to create a harmonious ‘win win-model’. Furthermore, the strategic, easily accessible location is being emphasised, and due to the increasing capability for production “SIP is transforming from an industrial park to a new town in East Suzhou”. Not unexpectedly, the video also refers to the prime example in this genre, calling SIP “the new Silicon Valley for entrepreneurship.”

Chinese businessman in the US – picture by Jonathan

Obviously, this does not mean that the development of SIP has solely been a success story. Due to a number of problematic aspects, the Singaporean government decided to disengage from the project around the start of the new millennium. Furthermore, there is general critique from economic geographers who question the actual knowledge transfer and the (in)visible ‘cluster effects’. It often seems unclear to what extent businesses actually profit from the so-called ‘local buzz’ of tacit knowledge.

Long live Modernism

Meanwhile in Belarus, local inhabitants are worried: They are sceptical about the idea of suddenly having a ‘Chinese’ city around the corner. Furthermore, they fear for inevitable deforestation. As a result of the industrial park development, many people will lose their (vacation) homes and a reservoir that provides a drink water supply to Minsk will also be threatened.

Panoramic view of modernist Brasilia – picture by Leondra Neumann Ciuffo

It is a little hard to imagine that Belarus, the most isolated country within the European continent with relatively low numbers of inward migration, will soon be home to a ‘Chinese-cosmopolitan city’ that functions as the high-tech gateway to the European Union. The ambition, as being stressed in a promotion video, is to create “an international city combining progressive industry and modern services, based on the harmony of nature, industry and innovation.” Similar to the Suzhou Industrial Park, the China-Belarus Industrial Park (will it get a proper name in the future?) is designed in the modernist tradition. In the spirit of Le Corbusier and cities such as Brasilia, there will be a clear separation of functions through strict zoning regulations: An ‘industrial’ city in the north; a ‘technical’ city in the middle; and an ‘attractive city’ with a so-called ‘entertainment core’ in the west. This latter part of the city is meant to function as a place where the international residents meet, socialize, and exchange tacit knowledge in order to inspire each other and to boost creativity.

Insanity, or promising initiative?

It is, to say the least, questionable whether this knowledge exchange will indeed occur to a large extent. Cluster effects have seemed to be hard to prove in many instances. Although one can only conjecture at this point, it is hard to imagine the appearance of a vibrant Belarusian-Chinese community. It is more likely to expect that many of the temporary Chinese workers that come to Belarus will struggle to assimilate, let alone that they will get along well with the locals. Apart from a shared communist past, the two countries have hardly any cultural similarities. Even in the current era of increasing globalisation, this is something that should not be neglected. The modernist design of the city is furthermore not of immediate benefit for creating a liveable, bustling and attractive place in which social interaction and creativity are automatically encouraged.

Apart from this, there are a number of other factors which make the successful future of this new development uncertain. Here, one could think of (geo-)political circumstances. Belarus is a loyal ally to Russia, and the relationship between Alexander Lukashenko and European Union officials leaves much to be desired. In case of political instability, the internationally oriented project can suddenly turn into a big failure, whereafter Belarus will be left with a ghost town on the outskirts of its capital.

But perhaps the future will be brighter and the park will indeed be a great added value to the modernisation of the Belarusian economy. In that scenario, it will at the same time facilitate increasing Chinese influence on the European continent. Are industrial parks like these fruitful blueprints for our cities of the future, or are they too technocratic and boring, and therefore doomed to fail? While many of us tend to state the latter, let’s just wait and see what happens here.