Havana, the capital of Cuba, has been founded in the 16th century as a trading place with a small fortress. With 2 million inhabitants it is the biggest city in the Caribbean. The layout of Havana is typical for Spanish colonial cities: a grid structure with central squares for specific activities. A wide range of architectural styles is characterizing the historical center, showing the long and rich history of the city. Over the last two decades, tourism became an important economic sector in Cuba and thus an important source of wealth in this country facing economic sanctions by most Western states. With more than 2,7 million visitors, tourism reached a new high in 2011. While most of the tourists come to visit one of the all-inclusive hotels at the seaside, Havana itself attracts a significant number of visitors.

There are a lot of accounts on how reconstruction in order to be more attractive to tourists is impacting urban settings, but how are people in a socialist economy affected by efforts to reconstruct the city center, in a society where inequalities are impossible by definition? This post will look at the effects of urban restoration in Havana, Cuba.

In the Revolution of 1959, profound changes in the economic system in Cuba were massively affecting tourism industry. Havana, once being something like the Las Vegas of the Caribbean, was a popular destination among wealthy Americans, as gambling was allowed in Cuba contrary to the U.S. Of course some shady figures were attracted to visit Cuba as well, to whitewash their money. Members of diverse mafia clans were frequent visitors. Their illegally acquired money was used to buy real estate or build casinos and hotels. Hotel Nacional is one of the most famous examples of this period.

The Revolution stopped these activities by nationalizing all property. In combination with the Embargo, tourism was almost impossible: U.S.- Americans were not allowed to travel to Cuba, people of most Caribbean and South American countries were not wealthy enough to afford a trip to Cuba. Tourism lost its importance (Schreiner 2008).

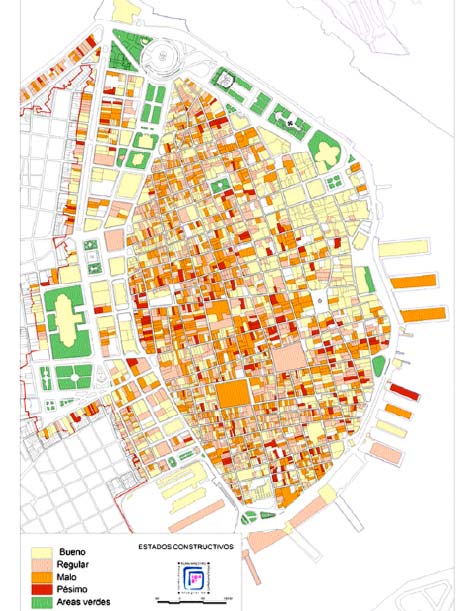

Due to economic circumstances construction of buildings slowed down, but especially the maintenance of buildings suffered from the shortages in the planned economy. Providing housing for the masses by building big modernist housing estates at the edge of the city was deemed more important. Buildings dilapidated and only most basic efforts to maintain the building were made, resulting in Havana’s particular attraction. It’s the city of decay, but without affecting the bustling street life. Havana is not a Caribbean Detroit, which is in total decay. Havana is a city with lively streets, as almost all the decaying buildings are still inhabited. The inhabitants fix with their limited opportunities what can be fixed manually by themselves, giving Havana its morbid but somehow romantic chique.

Only after 1989, when Cuba’s economy faced a huge crisis because the Soviet Union started to dissolve, tourism made its comeback under the conditions of a socialist planned economy in need of foreign currency. Decayed buildings in the city center that were deemed to be of value for the tourist industry were renovated and reconstructed. Step by step, this policy of regeneration extended to the whole city center of Havana, called Habana Vieja.

The designation of Habana vieja as world heritage certainly brought about a boost for reconstruction efforts of the old center, but mainly for the most iconic buildings. Efforts continued slowly, however due to the economic crisis after 1989, restoration came to a halt. In 1993, an enterprise has been founded with approval by the state of Cuba to continue with the reconstruction of the city center, called Habaguanex (Scarpaci 2000). This enterprise receives funding through shares of the earnings of businesses located in the old city center, combined with foreign investments, mostly from Western countries. Together with the Oficina del Historidor de la Ciudad Havana, Habaguanex determines the path of the reconstruction efforts.

Due to the process of reconstruction of the old center, a familiar urban phenomenon became visible: gentrification. In order to lower the residential density in the center – flats used to be overcrowded – people were forced to leave buildings in the center and move to other neighborhoods, often with modernist housing estates. So far, so familiar, but this has actually nothing to do with gentrification yet. If we look at the gentry, the group that gentrifies, a particular difference shows in Havana. The influx is not the wealthier, well-educated locals there to push out old residents, but a transient group made up of tourists or business people from Western countries and Latin America (Scarpaci 2000). Due to the reduction of residential density and the general reduction of flats in favor of touristic uses, displacement is a common feature of urban restorations in Havana, Cuba.

Interestingly, the gentrification process that is almost entirely researched in market economies also sweeps through neighborhoods in state-led socialist countries, financed mainly by foreign investments from the U.S. and Canada. Cuban officials argue this contradiction to the socialist ideals of Cuba with these words:

The disappearance of the socialist bloc and the USSR, along with the strengthening of the U.S. economic blockade… abruptly threw Cuba into the most complex moment in its [socialist] history…. The steps that we have been taking for the sake of the country’s economic recovery are part of an integral concept and not the result of isolated measures…. We’re not trying to fool anyone. We are not offering our foreign partners a transition to capitalism. Cuba is and will continue to be a socialist country. (Carlos Lage Dávila, Secretary of the Cuban Council of Ministers on the World Economic Forum, Davos, Switzerland, 27.1.1995; cited in Conas, 1995, pp. 7-9)

Cuba is forced to sacrifice parts of its socialist ideals in order to attract tourists and foreign investment. Thus, a particular form of gentrification occurs as a side effect of state-led efforts to renovate the dilapidated building stock in Havana’s center, pushing residents to distant parts of the city with lack of adequate infrastructure such as public transport, all for the sake of attracting tourists. With this process in effect, Havana’s character will change rapidly in the next years, losing lots of its morbid charm.