Today, we welcome guest author Marten Bolt, co-founder at Tikkieterug.eu with fellow students. He did his master thesis fieldwork in Los Angeles for the master Urban & Regional Planning at the University of Amsterdam.

“Forget baseball, litigation is the number one hobby of Americans”. Welcome to one of the most misunderstood countries in the world when it comes to planning, if one could even call it one country. The focus here will be in California, one of the most varied, and fascinating states. Oh, and the weather is great, which will push opinions over the edge easily.

This article will deal with do-it-yourself planning: Community Benefits Agreements, a new planning instrument which is the subject of my thesis.

To start with some simple facts: The United States are big. Driving from New York to Los Angeles is about the same distance as driving from Amsterdam to Baghdad. California alone is as big as Germany and the Benelux combined, which makes it easy to understand why all states have a big autonomy and all of them are self-governing to a very big extent. Planning is no exception to this rule. Therefore planning and enforcement of rules are largely local or state issues, and that is why I do not speak of the United States as a whole, but solely of California in this article.

Los Angeles is very different from most cities in Europe and the American East Coast and probably there is no equivalent to this city. In LA, one is nothing without a car. Although the city is trying whatever it can to improve public transportation and battle notorious traffic jams and car overuse, public transportation still is a nightmare due to very low densities in most far out stretched areas. LA does not have a real center around which the rest of the city has been built but is a hodgepodge of 80 districts in 15 different cities and Los Angeles County even has 88 incorporated cities which have their own small center of which this separate city is built around. Today, all these cities have grown over into each other, melting and fascinatingly uniting into one big opaque ravel of suburbs connected by concrete freeways.

Community Benefits Agreements

Los Angeles is known for its ethnic segregation; Koreatown, Little Italy, Los Teherangeles, Little Tokyo , Thai Town and Little Armenia are just some examples. In 1992, the black Rodney King was violently beaten by four white police officers when he resisted arrest. It was filmed by a bystander, George Holliday, who was coincidentally testing out his newly bought camera. Before this incident, existing tensions between Korean Americans and African Americans were attempted to be solved through talking and debating. During the six-day riots following the acquittal of the four police officers, despite the fact that the evidence was clearly against them, 53 people were killed, over 2000 people were injured and over 1100 buildings were destroyed by 3600 set fires. A lot of violence between the Korean Americans and African Americans erupted. After the riots, it was clear that talking was not enough; more drastic measures were necessary. Some years later, at the end of the century, the STAPLES Center was built by AEG; a stadium in downtown Los Angeles, near one of the poorest neighborhoods stacked with slum housing, filled with cockroaches, often run illegally by slum lords.

The L.A. Live project. Source: LA Live

In 2004, AEG wanted to expand the center to a real entertainment district named L.A. Live. The community living in the poverty-struck Figueroa corridor around it claimed they could not deal with more pressure on their neighborhood as this would mean a rise of parking pressure, more illegal evictions, and an estimated doubling of car crashes, and Los Angeles still remembering the 1992 riots, as they realized this big project in a very poor neighborhood could structurally contribute to more social justice. They co-operated with several community organizations such as SAJE and LAANE to protest against this development and united into a coalition, as all these coalition parties wanted to prevent another 1992 situation. Eventually AEG realized it could not build L.A. Live without choosing for a long line of delays, escalating costs and many court cases. The other choice was to communicate with the community and to find a way to get the community’s support for the project. After nine intensive months of meetings and negotiations, a legally enforceable contract was created called Community Benefits Agreement (CBA); the community promised to support the project, and in return AEG promised a parking program for residents, that 70% of the jobs at the project would be at living wage, local hiring, a job training program for low income and ethnic minority residents, and affordable housing. Eventually, the coalition and AEG considered each other to be reliable negotiation partners and just recently finished negotiating the Farmers Field project, an NFL stadium to be built in the same area, which again has big impact on the area.

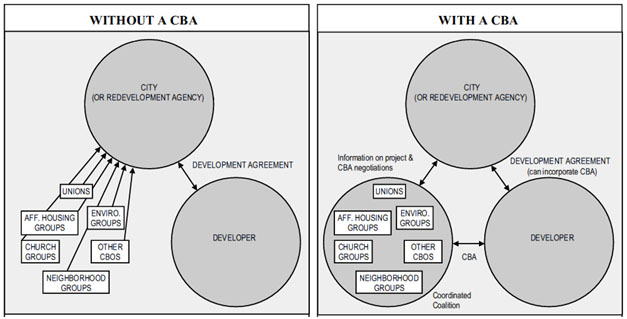

Since the L.A. Live CBA, many other CBAs have been realized over the United States, each with different rates of success, leading to CBAs being generally accepted in spatial planning in California, creating more justice in planning. Why are CBAs so interesting? In the figure below, the development process is visualized highly simplified. Immediately, one sees how orderly the negotiations become.

The negotiations in a development processSource: Murtaza Baxamusa, 2008

In theory everybody could be part of the win-win-win: communities can negotiate and enforce it themselves directly, thus creating real benefits because they know what they need. Governments can step back, thus having less pressure and less responsibility. Finally, the developer can use the CBA for the approval process at the city council to show a widespread support for the project, improving the odds of speedy approval for the project. Usually, the CBA (which is legally enforceable) contains elements such as affordable housing, local job hiring, living wage, public access to open space or parks, and a unique item for each coalition such as a private health clinic or soundproofing of buildings.

Of course, CBAs are far from perfect. To start, who decides who is the community? Nobody and everybody. It is up to the developer to decide if the coalition offers enough support leverage to get the project through the approval process. Another question could be whether the CBA is about people selling their soul to the corporation illuminati in return for small coin change. Probably, this CBA offers these people to ask benefits they would normally never get, and if they feel they do not get what they deserve, they should not sign this agreement and they could step out of the negotiations.

32nd Street in South LA. Note the contrast with LA Live which is just 2km away. Photo: Marten Bolt

Due to the high self-regulation of the American states and the relatively withdrawn governments as enforced by elections, the cities are tied down although they try whatever they can to improve conditions of the urban poor. The problem is; they are so limited in their possibilities and power, the actors keep each other in a sort of chokehold: the people want a small and limited government, whilst the government does everything it can, albeit to its limitations. Some voices are louder than others: often the richer voices are louder so the government is more or less forced to listen to those, leading to a big decrease in trust from the less rich voices which makes them dislike the government even more. The CBA is a very interesting instrument to kick-start projects for developers and for communities to receive well-earned benefits. Do-it-yourself planning at its finest.