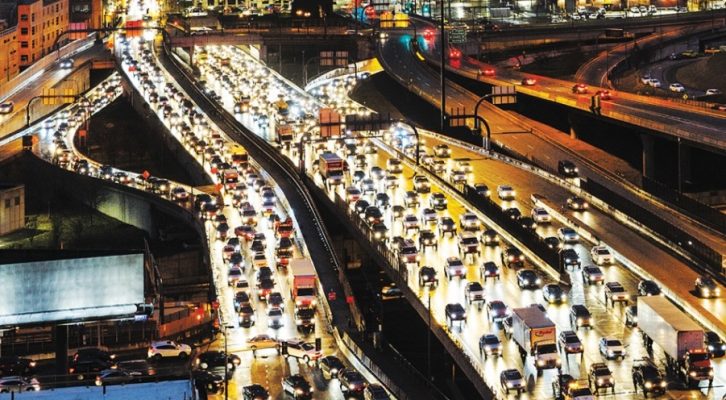

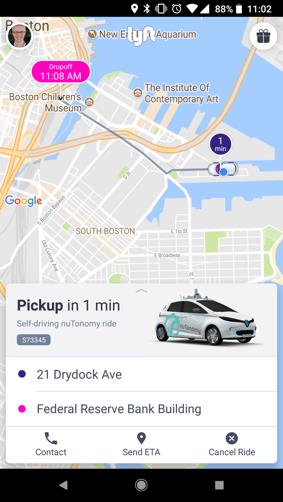

After moving from Europe, I discovered quickly that Boston, which was founded in the 17th century and is located on the Atlantic coast in one of the biggest metropolitan regions of the United States, is facing similar challenges as many European cities: unpredictable and extreme weather conditions and rising sea-levels, a growing population, steadily increasing prices, and daily traffic chaos of people trying to reach their workplace. Boston is the sixth-worst metropolitan area for traffic congestion nationwide, with the average commuter spending 64 hours stuck in traffic last year[1]. Approximately 787,000 people commute each weekday into Boston and large employment areas nearby, 71% of them by car[2].

The long road ahead: I-93 South at rush hour (Photo: Bob O’Connor, Boston Magazine 30.04.2017)

To counter these challenges, the Go Boston 2030 Vision and Action Plan outlines 58 initiatives with a combined cost of $4.7 billion aiming for zero deaths, injuries, disparities, emissions and stress for Boston’s transportation future. Better public transport, more walking, bicycling and shared services, and the introduction of autonomous vehicles are at the core of getting closer to these goals[3].

I pictured the autonomous revolution always in sunny west coast cities with their wide streets, which typically exemplify automotive America. I was surprised that Boston is not only eager to test self-driving, but also a forerunner. To say it in Frank Sinatra’s words: “if they can make it there, they’ll make it anywhere”. A technology approved in Boston’s difficult conditions – bumpy roads, rough winters with a lot of snow and ice, pedestrians crossing the street at red lights, and narrow downtown alleys – will work everywhere else as well.

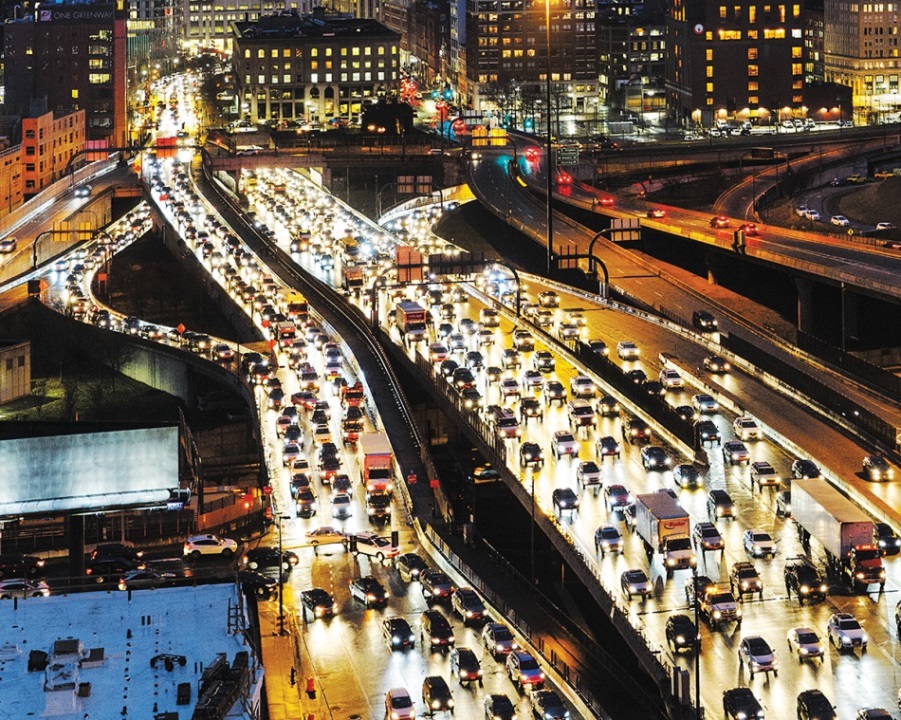

Thanks to Boston’s status as a technology hub, its openness to innovation, and political willpower, the City of Boston launched their autonomous vehicle initiative last fall in cooperation with the World Economic Forum and the Boston Consulting Group[4]. It shows first successes: customers of the ride-sharing app Lyft can now hail self-driving cars in the South Boston Waterfront.

Lyft’s self-driving pilot with nuTonomy begins rolling out in Boston (TechCrunch, 06.12.2017)

While opportunities and threats for future users and technology providers have been widely discussed in the popular press and academics, the influence of autonomous cars on the work of real estate developers and their motivations to shape the city remains largely unconsidered.

Opportunities of Self-driving Cars for Real Estate Developers

The combination of automation and sharing economy habits could reduce the number of cars and result in less downtown parking needs, as cars can circle around or drive themselves out of the city if nobody needs them. This would open up development potential for downtown garages and parking spots, and could be a great way to add density and maximize areas without wasting space on cars. Boston’s promising development pipeline goes in the right direction, either replacing garages or adding buildings on top of them.

Fortis Property Group plans a 10-storey, 253,000-square-foot spiral-shaped addition atop an existing garage: Dock Square Garage project, 20 Clinton Street, Bulfinch Triangle, Boston (BLDUP/15.02.2018)

Oxford Properties Group plans to purchase a 1950 garage in 125 Lincoln Street, allowing up to 223,880 square feet of mixed-use development (BLDUP/16.05.2017)

By eliminating the human error in driving, cars will require less wide lanes and less buffer to sidewalks and bike paths. This allows more efficient street planning and has the potential to result in an improvement of the aesthetics of streets and public spaces. Today, there is a sharp contrast of public streets and new buildings. Developers put tremendous efforts in creating an appealing appearance within their property boundaries, and particularly in the lobby design. While the lobby is the flagship of the building concept and incorporates characteristics of the knowledge-based new working world, the street just outside is not included in the holistic concept and not adapted to the digital age.

Crowded pick-up and loading zone in front of the Millennium Tower, Boston (Photo: Julian Bluemle)

The requirements of redesigning the public space create the opportunity to design a welcoming appearance and to brand the developments beyond their property boundaries. Developing the public zone around the building has the potential to add value and gain revenue by transforming former parking spots in cash flow generating structures, such as pop-up stores, kiosks and cafés.

Taxis and ride-sharing cars lining up in front of the South Station, Boston (Photo: Julian Bluemle)

The new, more pleasant driving experience, which allows passengers to work on the road or distract themselves reading books or watching movies, will make extended commute times more bearable and thus render undeveloped and remote areas around the cities more accessible – even for people without driver’s license. Places, which have not shown promising location factors under today’s commuting conditions because they seemed too far away, could suddenly receive more attention as distances matter less.

Threats of self-driving cars for developers

Locations, considered as very good today – amenity-rich, vibrant places with good access to classical individual infrastructure – might become less valuable. Companies might no longer strive to be located on major traffic routes. New Balance’s new headquarter, for example, is situated on the Massachusetts Turnpike because of its proximity to the beltway Route 128 corridor and to downtown. Hard location factors like this might become less important in the future.

The Warrior Ice Arena and New Balance Headquarters as viewed from the Massachusetts Turnpike (Photo: Robert Benson, Architects Newspaper, 10.05.2017)

In conjunction with the possibility that location might not be such an important factor for development anymore, the familiar quality and growth of trending areas and neighborhoods might become less predictable. Thus, the potential of densification, gentrification and increase in value in typically promising areas might shrink.

Furthermore, the branding and marketing of real estate might change, since passengers will no longer pay attention to what happens outside their car. The attention to company logos and other commercial representations along streets will decrease and their visibility will therefore become less important.

Signs of the World: Citgo Sign, 660 Beacon Street, Kenmore Square, Boston (https://landmarksignsincblog.wordpress.com, 23.07.2013)

The lack of passengers’ eyes on the street creates another disadvantage: streets risk becoming more insecure, because passengers do not have to pay attention to their surroundings anymore and even if they do, they might not be able to stop, change direction, and intervene. Already over fifty years ago, writer and journalist Jane Jacobs famously studied and wrote that one of the main characteristics of a thriving urban center is that people feel safe and secure in public spaces, despite being among complete strangers. She argues that urban security is not simply a matter of policing, but that “eyes on the street” provide informal surveillance of the urban environment and create collective identity, making public spaces more secure. A large portion of these “public eyes” will be lost in the future with more inward-looking car passengers. The threat of higher crime rates, in turn, could lead to decreasing property values, if not counteracted by attracting more pedestrians and cyclists to the street and making public places to welcoming and pleasant locations to linger.

Deserted street in Boston (Photo: Mark Simpson, https://twitter.com/marksimpsons, 19.04.2013)

Moreover, the origin-destination and door-to-door traffic is likely to increase significantly, since self-driving cars always need a clear address. This will eliminate spontaneous stops and jeopardize shopping, commercial, and restaurant areas that aim to attract customers with their exterior appearance and branding.

Despite car-sharing and synchronized traffic flows without human errors, downtown traffic is likely to increase overall, as self-driving cars opt to circle instead of parking. Gridlocks and congestion of the city center badly influence property values, and incentivize even more people to move further from city centers.

Overall, whether the advantages outweigh the disadvantages of self-driving cars will depend largely on how exactly individual cities react to their introduction and drive potential positive changes. The cities’ personality and atmosphere will continue to be a major driver for real estate developers to evaluate if potential tenants and investors like or dislike a city. It seems evident that developers should collaborate more closely than ever with the cities in order to shape and conserve the character of the cities.

Future Role for Developers

To preserve predictable conditions and a steady development potential, it will be important to further increase the qualities of the cities. Infrastructure will be an essential component of these qualities. Locations with a tapestry of different transportation modes – biking, walking, subway, and self-driving electro buses and cars will provide great development potential.

Boston made many good steps in the direction of a walkable, compact city center and is steadily advancing public transport and bicycle paths.

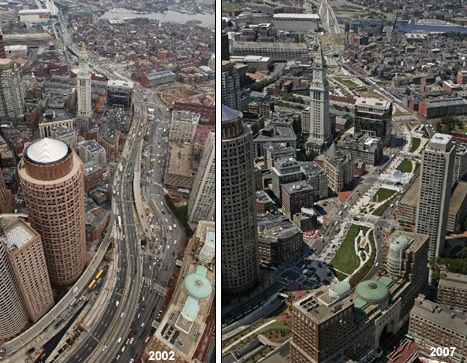

Above all, the Big Dig is worth mentioning as an example: Massachusetts’s three-decade-long quest to bury the Central Artery, Boston’s major interstate highway, and build a new underwater tunnel to Logan International Airport.[5] Investors and residents responded positively to the infrastructure improvement. Commercial properties along the old Artery increased in value by 79 percent in fifteen years, nearly double the citywide increase of 41 percent.[6] The increase of quality is visible for example in the adjacent North End, where Italian restaurants are setting up sidewalk cafés in locations which used to hide from the highways.

Before and after shots of the Central Artery and today’s Rose Kennedy Greenway (Boston cyclists union, Casey and a brief history of highways in Boston, 17.01.2012)

Projects of similar magnitude might be necessary to transform cities in favor for self-driving cars. However, city governments will face increasing difficulties to fund these projects. The revolution of self-driving cars might bring significantly decreasing incomes through parking fines and tickets, which sum up to 67 million per year in Boston.[7] City treasuries might suffer an even bigger hit if rich residents decide to move out of the cities to quality suburbs and the back country.

Scene along the pedestrian walkways next to Faneuil Hall Marketplace (Photo: Lord and Taylor, http://www.10best.com/destinations/massachusetts/boston/)

This is a unique chance for developers to step in, join forces with the city government, and to take the initiative for an improvement of the cities’ qualities by making the city more people-friendly and less car-friendly by providing more space available for cultural and leisure activities stimulating life in the city. Developers will benefit a lot from the efforts of better use of public space and improved public and automated transport, leading to a lively city with short distances and compact diversified neighborhoods.

I hope that the developers will seize the opportunity and realize that their projects need to adapt concepts for self-driving cars in the future. The sum of many tiny steps will help to improve the cities.

[1] Go Boston 2030 Vision and Action Plan, https://www.boston.gov/departments/transportation/go-boston-2030

[2] https://www.boston.gov/departments/new-urban-mechanics/autonomous-vehicles-bostons-approach

[3] 2015 urban mobility scorecard, national congestion table, p. 18

[4] 2012 travel patterns, Boston region metropolitan planning organization

[5] City journal, Lessons of Boston’s Big Dig, by Nicole Gelinas, Autumn 2007

[6] The Boston Globe, 2004

[7] Governing/ How autonomous vehicles could constrain city budgets/ Mayor’s office, Office of Budget Management 2016