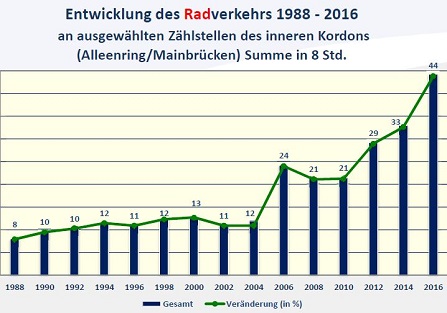

Every morning the same thing. I hop on my bike and surf the roads while having just one thought on my mind: “How would Frankfurt look like when one out of two persons would use the bicycle to get to work?” Less traffic. Less pollution. More joy. Yes, it’s a dream. And no, it is not impossible. Frankfurt’s (Germany) local cycling advocate ADFC Frankfurt has a clear message: “in 2025 should 25% of all urban trips be completed by cycling. And it doesn’t actually seem to be a farfetched idea. For example, whereas in 2004 the modal split for cycling was only 7%, currently it is already 17%. The last figures of the RadfahrBüro (responsible agency for cycling) showed similar figures: an 80%(!) increase in cyclists in the inner-city between 2014 and 2016 (see graph). These are big numbers and amounts for change. But then again, why not? Cycling is gaining more and more support by local governments, inhabitants and users of traffic for reasons of city accessibility, a healthy lifestyle and, after the large diesel scandal of the German car companies, clean air. Basically, if one considers the whole package, as a city legislator, there is no reason nót to invest in cycling infrastructure. But will this actually happen? Is the environment of Frankfurt facilitative enough to cycling?

Development of cycling traffic between 1988-2016 (source: Radfahrbüro)

After having moved to Frankfurt am Main a couple of months ago, I went out and did some research. I asked myself these three questions in order to grasp Frankfurt’s potential:

- Is there a bicycle renting scheme? After all, every city, serious enough about cycling, starts with a renting scheme for bicycles.

- Can you actually cycle? How do the city and its streetscape facilitate cycling? What kind of infrastructure is in place?

- Do people want you to cycle? How do people see cycling? What discussions are going on in the city? In other words: what is the socio-political discourse on urban cycling?

-

The bicycle renting scheme

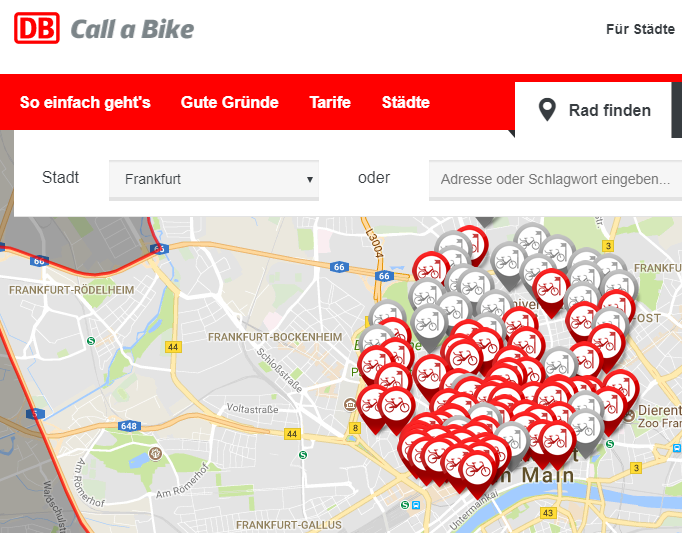

The starting point of every city serious enough about cycling is the bicycle renting scheme. How does that look like in Frankfurt? Well, first of all, there are several bicycle shops that rent out bicycles. However, arguably the most well-known renting scheme is the DB’s “Call-a-Bike (flex)”. Scattered around the city, there are numerous bikes to be found and to be rented. One only needs to register at DB to be able to make use of the system. Finding a bicycle shouldn’t be the problem (see illustration).

Call a bike renting scheme (source: DB Call a Bike)

It is undoubtedly a well-used renting scheme. Every day, one can watch the roads of Frankfurt and find the DB symbol passing by. Besides that, the DB Call-a-Bike is a ‘flex’ system; bikes are not connected to a fixed point, but are positioned around the ‘call-a-bike’ pole. From the users’ perspective, this might be a great benefit: a station is never ‘full’. One can park basically everywhere around the designated pole (literally a pole). And therefore, one never needs to find a place to park ones bike.

But then again, in the longer term, there might actually be negative consequences for the users themselves. To grasp this argument, we need to consider it out of the outsiders’ standpoint: the standpoint of perception. From an outsiders’ point of view, this system actually looks kind of juvenile, uncoordinated and even haphazard (see photo below). Bicycles can essentially be stalled crisscross on the sidewalk. Some would even argue, in a city where cycling is not the predominant mode of transport, presenting the bicycle scheme as it is now, actually reinforces a perception of cycling as being a marginal, insignificant, and perhaps even a neglected mode of transport. In this perspective, one needs to reserve space for bicycle parking exclusively, if one wants to emphasize the socio-political endorsement of a balanced modal split: besides cars, pedestrians and public transport, actually including cycling.

Considering the bicycle scheme, Frankfurt receives the points for the many bikes and not to forget its usage. In terms of presentation, which is important to educate people by reinforcing a perception of inclusion, Frankfurt seems to have a long way to go. Having said that, let’s look into the following question:

-

Can you actually cycle?

If there is a bicycle scheme there surely is some kind of way to ‘surf’ the roads, isn’t it? An honest answer to this question is: yes, there is space to cycle. There are numerous bicycle paths, sometimes assigned on the road itself, sometimes blue or grey-tiled patterned on the sidewalks. Bicycle signage is also existent. One is led to the larger destinations (such as Bornheim or Museumsufer) by the green colored signage. Besides, cycling itself is generally pleasant; the city is as flat as a city can be. Yes, there are some fly-overs, and it gets steeper once you get to the north, but being located around the valley of Rhein-Main, the city really asks to be cycled in/through. Also, the city legislation allows cyclists to cycle in ‘Einbahnstrassen’, which generally means: cars can only go one direction; the bicycle can go in two directions. On top of that, there is even a bicycle-street in the center (Goethestrasse). Okay, the pavement consists of cobbled stones, which makes for a massage and the street is still largely used by cars, it is a cycling-street nonetheless.

In spite of all the aforementioned, there seem to be more fundamental flaws in the cycling infrastructure. The first is undoubtedly the diversity of cycling infrastructure. If one cycles through the city, one finds himself on roads with cars, on designated parts of the sidewalk (as this movie shows), then on an exclusive cycling path, perhaps after that a blue signaled bicycle street, and ending with a little dirt road through the park. The infrastructure is largely inconsistent and cannot be seen as an interconnected system. There are some fragments in which you could argue, the cycling infrastructure is great, followed by parts where cyclists are not part of the city’s transport planning. For example, you can look at the picture where the bicycle path suddenly ends. Or, you might have to bump onto a sidewalk where a small bicycle path is provided (see photo below). This incoherence in space, color, and so forth, makes the infrastructure and the position on the road for cyclists rather ‘unreadable’. As a cyclist, you might feel in 40 to 60 per cent of the times: am I actually supposed to cycle here, or should I be somewhere else?

The above is undoubtedly connected to the fact that cyclists share the roads mostly with cars. As these modes of transport have largely different speeds (cars generally faster than bicycles) and require different amounts of space, these two modes are generally considered to be in conflict with one another. If a city has the space, separation seems to be the safest way to go. This argument also goes for pedestrians and cyclists. Cyclists are generally faster than pedestrians (unless someone stole something and has to run from chasing police dogs). If one puts cyclists and pedestrians together, one makes for a space wherein cyclists feel uphold, and pedestrians feel vulnerable. Therefore again, if a city has the space, one might consider separation.

And perhaps that’s one of the things where space becomes political. If one just glances over Frankfurt’s city streets, one will not have difficulty in recognizing the amount of space parked cars are occupying (even ón the bicycle paths). As a now experienced cyclist in Frankfurt, I find myself generally riding in between cars: on the left they are driving, on the right, they are parked. In these situations, I cannot help but jokingly think: if one is not hit by a driving car, one might as well be hit by an opening door. Whether or not the situation of parked cars is an accepted or a desirable situation in local culture, it undoubtedly does affect the possibilities of producing city space which caters for a balanced modal split.

Frankfurt, again, receives the points for actually having cycling infrastructure, but again, it has to have an integrated, rather than a fragmented system to become the pleasant cycling environment many want it to be.

-

Do people want you to cycle?

All the things about how to improve can be put aside if people do not want you to cycle. In other words: what is the public discourse on cycling in Frankfurt? From a pure legislative standpoint, there are different (political) bodies involved in endorsing cycling behavior. One which is arguably most on the forefront is the ADFC (Allgemeiner Deutscher Fahrrad-Club), with political spokesperson Bertram Giebeler: A lifelong advocate for cycling infrastructure and fierce critic on the current situation of cycling in the city. They are the ones that conduct a German wide study on cycling infrastructure and put different cities in perspective. Outcome? Frankfurt scores 12th out of 39 . From the city government itself, there is the RadfahrBüro Frankfurt, dealing with research on cycling behavior and further development of cycling infrastructure.

The local newspaper Frankfurter Rundsschau seems to have positioned itself in favor of cycling in Frankfurt, considering it is more than regular reporting on city cycling.

The endorsement by these different parties does result in different benefits for cyclists. One of them is, that you can take your bike on basically all public transport at all times. You never know if the weather keeps it like it does in the morning. So when it starts rushing in, you might as well take your bike on RMV’s well-connected S-Bahn, U-Bahn, tram, train or bus. Apart from that, in the next month another 96 bicyclesstalls are installed in the city centre. Also, there are far-reaching plans on a cycling highway between Hanau (city close to Frankfurt) and Frankfurt [https://www.region-frankfurt.de/rsw], which will connect the two cities for the daily commute.

Apart from these arguably supportive changes, we might also consider the behavior of other users of the urban infrastructure, for example car drivers. As cyclists are underrepresented in daily traffic, one might experience the inexperience of both cyclists and drivers to share the lanes. This inexperience is shown in hesitance, unexpected behavior and even pure ignorance. As I surf the roads basically every day, I would say that 9 out of 10 times car drivers are considerate; they leave generous space between the cyclist and the vehicle, wait for cyclists when they come from the right and share the road quite reasonably. And yes, as a cyclist, I now and then come across aggressive car drivers perhaps not realizing how it feels to be more vulnerable on two tires and perhaps therefore leaving less space to cyclists. And yes, I also encounter really aggressive car drivers who actively look for conflict in accelerating speed, honking the horn or giving gas to let the cyclists know they are right behind them. The so-called ‘look’ (when a car driver is angrily looking the cyclist in the eye) is also not something irregular. Then again, it is without a doubt true that cyclists are unpredictable, more than once drive through red light and use the space for cars even though there is also a slim biking path on the sidewalk. This all might seem quite unfair to car drivers, which mostly do comply with the rules. But this only, will not explain the experienced aggression. There might be something deeper to it.

Mutual aggression explained

When one considers the urban form of Frankfurt, it doesn’t take long to conclude the city is a so-called “Automative City”, a term widely used in urban planning. These kinds of cities cater for the individual transportation of people through highways, many parking spaces, ample opportunities to park your car on the drive way or partly on the sidewalk. With the rapid growth in automobiles in the 50s and 60s, many European city governments actively planned for the Automotive City. One might consider Rotterdam to be one, and believe it or not, even Amsterdam has had large highway development. In Germany there are obviously more of these cities, such as Cologne, Stuttgart or Munich. Given this, the current dominance of car favoring infrastructure in Frankfurt gives the daily feedback to current traffic users that only the car is in the right place, whereas cyclists and pedestrians have to constantly discuss and argue for their space in the city while crossing the road (as grassroots initiative Critical Mass argues). As infrastructure in general is a scarce resource, it is always on the verge of being politicized, especially when behavior of infrastructure users is changing steadily.

In relation to this, it is relevant to look at the social psychological theory of realistic conflict theory. This theory argues that aggression, conflict and hostile behavior arise from competition over resources which are scarce as well as valued. In this particular case, urban traffic infrastructure is the resource. And yes, it is becoming scarce. Cyclists pose a threat to the current – and pleasant – situation of car drivers. They are using space formerly solely reserved for cars. Also, it is a direct threat as the driving experience for drivers becomes more complex. For the driver, there is more to worry about. The behavior of cyclists is therefore an instant red flag for occupation and disconformity. No doubt, hostile behavior will actually get to the fore even more, when cyclist infrastructure is getting ever more integrative and will occupy more space than it does now. In the end, it will mean a direct loss for drivers.

Looking to the future

To overcome this feeling of loss and the connected aggressors, there is perhaps not even that much to be done, other than really advocating for a paradigm shift in what is considered to be ‘normal’. As the built environment currently shows, having a car in the city center is ‘normal’, cyclists and pedestrians will stay in the margin. Once government and advocacy bureaus are publicly endorsing Frankfurt as a cycling city, there might be a change. Having said that, to manage such a tremendous rethinking in the country of ‘Autoherstellers’ is for the ones responsible perhaps suicidal. Even the widespread Kartellisation and misleading of the major car companies does not seem to change that. Or will the city actually follow the car banning policies which are discussed in for example Stuttgart, Munich and Cologne? So far, it has been quite silent in Frankfurt when it comes to banning cars.

To have a more balanced modal split in the city will nevertheless mean that cyclists and pedestrians will have more space in the city. Luckily, the city does have a lot of space to facilitate for this. The streets in Frankfurt are tremendously wide, but that hasn’t yet been translated into an integrated system for cycling. Before that time comes, cars and cyclists will have to try their best in sharing roads, even though that might mean the pleasant commute is under pressure for both.

- Bicycle path on the sidewalk of Mendelssohnstrasse (own picture)

- Hopping on and off the sidewalk (own picture)

- While you cycle and your path ends suddenly (own picture)

- Cycling signage in Frankfurt (own picture)

- Allowed cycling on einbahnstrassen (own picture)

- Cycling path suddenly ends (own picture)

- Cars are generally parked on both sides of the street (own picture)

- Cycling along the highway, typical for Automative Cities (own picture)