Streets exist in many forms. From large, straight and open, to small, winding and secluded. Streets have different meanings to different people. For one it might be the way to work, for the other a place to hang out. Especially in cities, streets are multidimensional, multifunctional and multi-interpretable. Streets are there for movement, place making and public life. That is, in cities where they plan for inclusive streets, in which this multi-dimensionality is accounted for. In other cities, one recognizes the more reductionist concept of the street: a street solely meant for movement. In these cities, place making and public life are not considered in their urban design. One of those cities where one can observe this tendency is Frankfurt.

The car saturated city

Frankfurt is a typical automotive city. Whereas in the 20s, 30s and 40s most people used their feet, the bicycle, the tram or the carriage, this changed dramatically with the widespread availability of the revolutionary motor vehicle. Not the feet, not the bicycle, but the car was considered to be the future mode of transport. Once also the urban governments and planners were convinced, it often went fast. Like other cities in Europe, Frankfurt changed its streets and housing blocks for the benefit of the once believed bright and modern future. In the 50s and 60s, cars were everything. Cycling, and to a lesser extent walking, were passé.

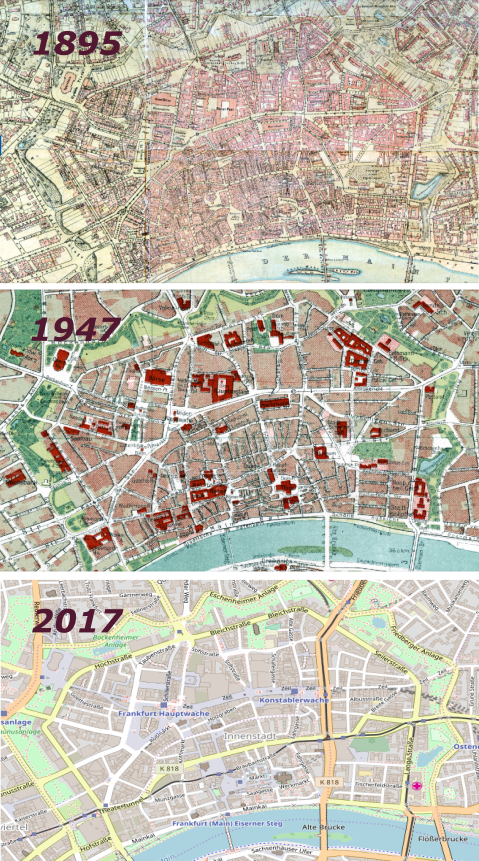

The changes in Europe were dramatic in terms of modal split, streetscape and land use. The modal split of bicycles declined from 50 to 85 in the 40s and 50s to only 14 to 35 percent in the 70s. The streetscape changed partly because of the development of large four way highways, even through the city centre: see maps from 1895, 1947, 2017 below. With regards to land use, a vast amount of parking lots needed to be reserved. Former public space transformed to cater for the individual mobility. Next to train stations, work and housing lots, people had to make way for the car.

The changes of the Inner-city of Frankfurt in 1895, 1947, 2017 – source: GeoInfo Frankfurt and OpenStreetMap.org

With the introduction of the car problems arose: congestion, air pollution, suburban sprawl and a dramatic rise in traffic injuries and fatalities (3214 in Germany in 2016).

Several European cities chose to counter this development and discouraged car-use while encouraging cycling and walking. One might think of Oslo, Copenhagen, Hamburg, Berlin, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Utrecht and Groningen. The modal split of cycling in those cities crumbled back to 25% on average.

Frankfurt seems to have missed that turn. The financial capital of Europe is still planning for the car and is seemingly forgetting streets are also made for public life, cycling and not to forget: walking. The reductionist concept of the street as being a place solely reserved for movement is still very much in place in local politics, but is surely outdated. City streets are paramount to public life and place making. In order to assure such an environment while staying within the realm of what is physically possible, one could start reserving less space for vehicles and more for humans: in this case, pedestrians.

The distance perspective

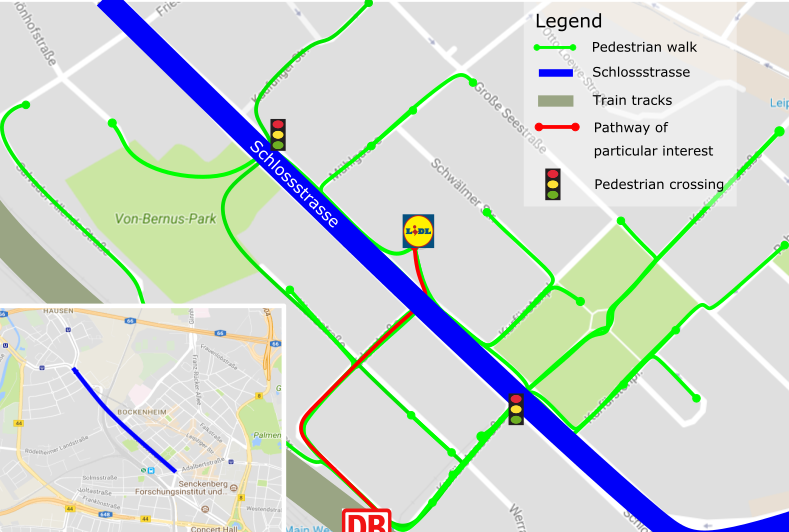

In addition to this argument one might look at the difference in daily trajectories between cars and pedestrians. Not surprisingly, pedestrians cross shorter distances than cars. The movement is therefore more focused on the inner-city. These consist of people’s daily routine movements: walking to work, to public transport, getting their child from the kindergarten, making a stroll in the park or doing their daily grocery shopping. Out of all these smaller movements, one could draw a whole network of daily trajectories on the neighborhood level, intercrossing each other and creating a dense web of lines (see green lines in illustration below). These are important lifelines of urban mobility.

How different that is with cars. Cars are generally used for the larger distances. The movement is therefore focused on inter-city or rural-urban movement for reasons of leisure, work or family and friends.

Given the longer distances of cars and their usage of throughways that cater for this behavior, these streets essentially become physical obstacles for the daily walking patterns of many inhabitants. On the one hand they form a red carpet for people that like or need to use their car. On the other hand they form a river that is to be crossed by people living on either side of them. That is not to say, these inhabitants are not using that throughway. They are only using it in different ways.

If this is the case, there is an argument for streets to be ‘inclusive’ in order for them to be welcoming to all (pedestrians, cyclists; local inhabitants) instead of only the few (car). How the above works out is lovely shown in Bockenheim, where a vital daily trajectory of people living in the neighborhood happens to be on either side of a larger throughway (the Schloβstraβe).

The Schloβstraβe and Ederstraβe

Before we get into the actual problem, we need to introduce the two streets in question: The Schloβstraβe and the Ederstraβe (click here for interactive Maps-section). The Schloβstraβe is a typical throughway. The North-South axis connects the City Centre (Messe, Westend and Bockenheimer Warte) in the South with the residential area Hausen and the intercity highway 66 in the North. The Ederstraβe is much smaller. It is a street connecting the very important ‘Westbahnhof’ with the Schloβstraβe. It is as well the most important access road for the neighborhood (the Wasserstraβe and the Kasseler Straβe). Also, and this is perhaps the essential aspect of it all: it directly leads to the supermarket Lidl.

And exactly this is where the problems arise. Unfortunately for the people living on the West-side of the Schloβstraβe, the Lidl is located on the East-side. For their groceries, they need to cross the road.

“Crossing a road? And you call that a problem?!”

Indeed, this sounds a little dramatic, given the idea that crossing a road in a Western-European city shouldn’t be the largest of our daily concerns. Except, if you think of how Frankfurt has developed its mobility from the 50s onwards: developing for cars at the cost of pedestrians.

Namely, in order to cross this road as a pedestrian, and succeed in your goal to get your groceries, you need to jaywalk. Why? Because there is no pedestrian crossing. This road is, in other words, solely for traffic on tires: cyclists and cars.

And it shows itself. I cycle that street every day, and every day people risk their safety and disobey the rules for the simple reason they are totally left out of the planning practice. In this crossroad, there is no place for people’s daily pathways, at least not for the ones that are getting their groceries at the local shop (see illustration before).

There simply is no crossing.

On the day I took the pictures and observed the way numerous people used and crossed the street, one thing struck me the most. It was not the guy right in time to jump away from the driving car, nor the man waiting for a couple of minutes in order to be able to cross safely. It was not the old lady, even though it took her a couple of minutes to cross the road. It was the vast amount of people using this ‘self-invented’ crossing. As much as this might show the way streets are in itself defined by its usage, it still remains a lack of recognition for pedestrian space.

Plan for the inclusive city: develop streets for all

It seems reasonable to follow the line of the inclusive city: planning streets for all of its users and using a wider definition of ‘the street’. And not to forget: taking care of the most vulnerable ones in traffic: pedestrians.

But how? What can possibly be done to develop the Schloβstraβe as such that it caters for the actual behavior of its users?

There are two things:

- Make a zebra-crossing in order for pedestrians to cross safely

- Reshape the streetscape in order to provide more space to all users

The first thing to do seems to be quite simple: a zebra crossing would do the work in order for people to cross safely. See for example this rather infantile, silly, cheap, own made illustration of how that might look like.

The infantile, silly, cheap, home made illustration of the more secure zebra crossing for pedestrians (goes without saying it is my own illustration)

When it comes to point 2, reshaping the streetscape, it entails more complexity. Nevertheless, it is possible. As one can observe in the pictures, the street is largely reserved for cars. Also, there is a large amount of space reserved for the tram-tracks, even though they are scarcely used for reasons of shunting trams (perhaps one to two times every day). This street still very much pulls in a large flow of traffic by its welcoming throughway character. Changing its character needs some imagination, but as other European cities have shown, it functions.

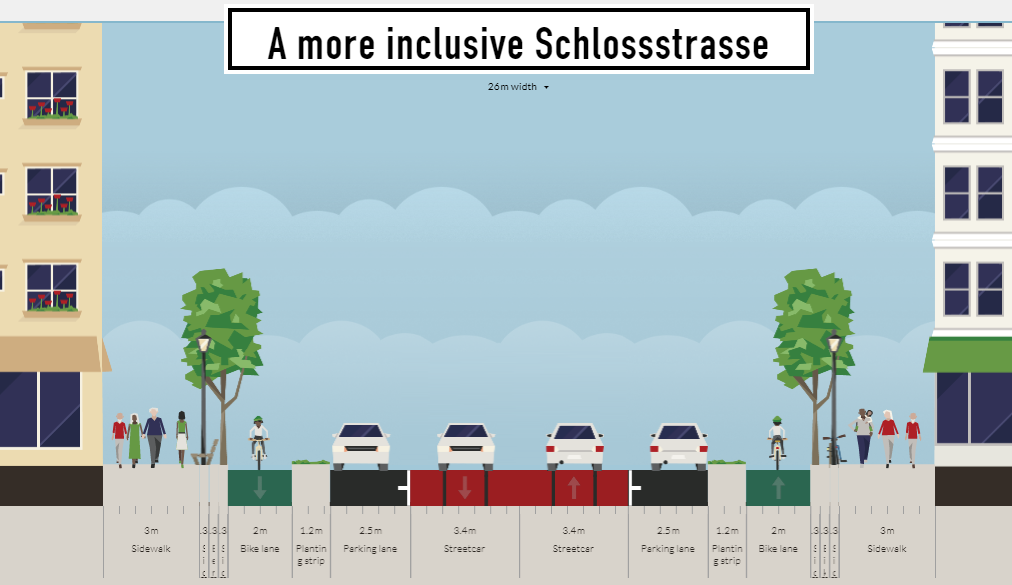

As to help the reinvention of the Schloβstraβe, we visualized the current situation and the preferred situation (helped greatly by the App RE:Street). By measuring the street on our own, minor mismeasurements should be accounted for. Our measurements ended however between 26 and 27 meters. To be on the safe side, in the visualisations we went for the defensive 26 meters.

The Schlossstrasse – How it is now (own visualisations, with thanks to Choi Seungmin and the RE:Street App)

To reshape the street we used examples of other cities throughout Europe in discussing the pros and cons of various strategies. A long story short: we tried to account for the overwhelming evidence that separated bike lanes are preferred in terms of movement and that space for pedestrians and greenery is vital to an inclusive Schloβstraβe. In our visualization, the space for pedestrians has increased by almost 100% (from 2 to 3.9 meters). The space for cyclists has increased by 33% (from 1.5 to 2 meters). The space for driving cars stays the same (3.4 meters). For parked cars, the space actually becomes wider (from 2 to 2.5 meters). The tramtracks are in this proposal still usable, as they are now shared by cars and the sporadically passing trams. Apart from that, cars are physically removed from pedestrians and cyclists. In this way, we make sure that for áll users of traffic, the street becomes less stressful.

So much space to offer

This visualisation shows perhaps the peculiarity around the car saturated city of Frankfurt. The city has so much space to provide, that a restructuring of many streets will in the end not even affect car mobility that much. Nevertheless, it will make for a more inclusive city by providing a pleasant environment for a larger segment of the population than it currently does. Simultaneously, it will provide more space for the multi-functionality of city streets. Streets that include space for movement, as well as for public life.

Want to know more about our cycling experiences in Frankfurt? Click here!