A recent satire released on syruptrap.ca entitled “Vancouver ranked the most city in the world,” exemplifies the usefulness and wealth of information one can learn from a think tank’s city rankings, that being nearly nothing.

The article’s headline is all too common for Vancouverites as they browse their newsfeeds or read the paper. The city is consistently ranked among the most liveable on various surveys produced by think tanks from around the world. It is a predictable and repetitive story. The media will speak praise about Vancouver’s climate and access to nature while images of Yaletown’s skyscrapers juxtaposed against the North Shore mountains dazzle on the screen. The headlines about our fair city give us warm and fuzzies for a minute or two and then we go about our daily lives.

While it is nice to hear that people in an office somewhere thinks our city is great, these surveys are problematic in that they are used by the media to justify and propagate false narratives about cities while ignoring real social issues, or they are plain wrong due to methodological errors.

Stanley Park is the largest urban park in North America and contributes to Vancouver’s rankings on livability indices (Photo: Grant Diamond)

While cities once competed at a regional scale, globalisation has seen competition for investment and capital turn international. Cities compete to be the most creative, sustainable, livable, and so on, and market themselves to project this image. By being the most something, a city can attract investment as it is viewed as a desirable place. Liveable cities are viewed as the prime place to grow a cognitive-cultural economy and attract the creative class and one way this is marketed is through city indices.

It seems impossible to reduce the workings of a city into a quantitative study that uses a few numbers to validate blanket statements and it probably is. Cities are dynamic and their collective images are generated through infinite individual experiences and actions. They layered and are home to different communities that are constantly forming, disappearing, and changing. These experiences and perceptions cannot be converted to numbers despite the efforts of various think tanks. Regardless, I do not need to argue here that urban sociology cannot be summed up in a spreadsheet.

While city indices such as the Liveability Index have issues related to quantifying unquantifiable data, they also have much simpler methodological problems. For example, in 2011 Vancouver lost its reign as the Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) most liveable city and fell to third place. The EIU cited traffic congestion as a reason for this fall from grace, stating that a closure of the Malahat Highway contributed to Vancouver’s lower score.

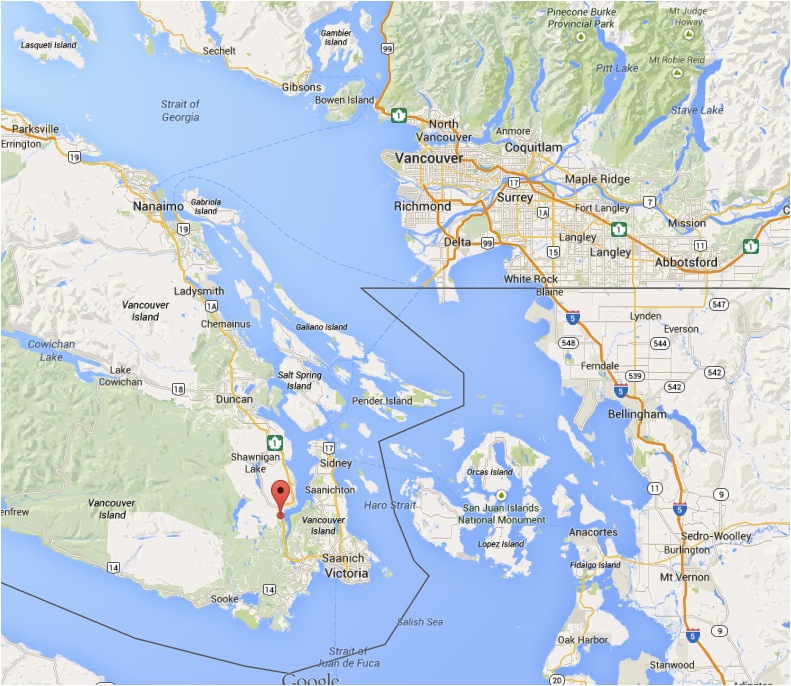

Apparently, the EIU decided not to look at a map when producing this data: the Malahat Highway is some 80 kilometres from Vancouver and across a large body of water having virtually no impact on the city’s traffic. Locals and the media alike immediately condemned this geographic ignorance, (unfortunately similar to the geographic approximation that resulted in the US exclave Point Roberts over 150 years ago) despite assurances from the EIU that its data was sound. If the EIU can so obviously overlook geography in their classification scheme, what other shortcomings exist in their data?

The Malahat Highway is roughly 3-4 hours from Vancouver including a 90-minute ferry ride. (Google Maps)

Indices such as the Liveability Index ignore real world problems in cities and fail to acknowledge any notion of what liveability means to the average citizen in the city under study. For example, while Vancouver is a beautiful, exciting, compact, and cosmopolitan place – it is simply not affordable to many people. The globalisation of the world economy has seen an influx of foreign investment into cities and in Vancouver foreign ownership in the housing market is commonly referred to as the reason for its housing bubble. This began to accelerate after the 1986 World’s Fair, whose brownfield site was sold to a Hong Kong developer that has developed the neighbourhood into one of North American’s most popular and expensive places to live. The spillover effects have seen Vancouver become one of the world’s least affordable cities. Vancouver is now known worldwide as being a great place to live and reports such as the Liveability Index only perpetuate this notion to elites who have the means to participate in this economy, much to the joy of developers.

Do you want your city to be the most? Then follow the EIU’s lead and manipulate the data until you get the result you want. Berlin can be the most hipster; Amsterdam the most canal; Boston the most sports; the options are endless! Don’t forget to ignore issues that oppose your purpose.

Considering this example is produced by the EIU, it is unlikely it is intended for the average citizen but rather the business elite. It is therefore meaningless to most of us, just like the Syrup Trap article’s title “Vancouver ranked the most city in the world.” It would be appropriate then for the media and civic governments to treat it this way and focus on real issues facing the city such as affordability and homelessness.