In this article, two cities will be compared that are separated by 6,603 miles: Edinburgh and Kuala Lumpur. It is legitimate to question for which purposes such a comparison can be useful. While the last paragraph of this short essay will briefly reflect upon this debate, the most relevant similarities and differences between the two will first be highlighted.

Urban population growth

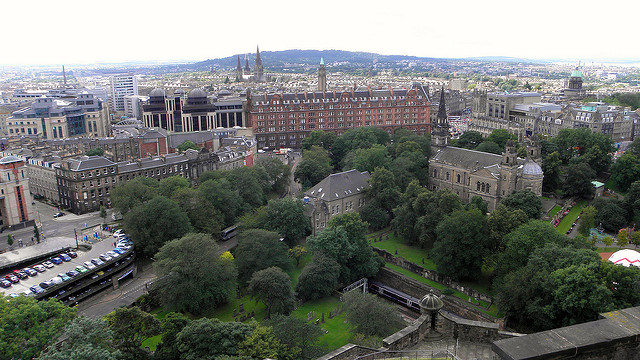

Edinburgh is the capital of Scotland and has about 524,000 inhabitants. The city has a long and rich history, which is for instance exemplified by the fact that it was the first city in the world to have its’ own fire service. It is currently forecasted that Edinburgh will experience a population boom: its’ population will increase by about 50,000 people, which is a growth of about 10 percent, within the next 10 years. This leads to a number of serious challenges for the public services of the city. What is called a boom with regard to Edinburgh, however, would be a very modest population growth if one looks at the demographic development of Kuala Lumpur, where the population is expected to increase by about 1.5 million people, or 20 percent, in the upcoming decade.

Population dynamics in these cities thus differ significantly in terms of scale and speed, but why does this matter? In the following, I will argue that even though Edinburgh and Kuala Lumpur may appear being very different at a first glance from an outsider’s perspective, there are actually some similar (neoliberal) processes that can be observed. In order to present evidence for this argument, some infrastructure projects that are currently carried out in the two cities are highlighted as comparative examples.

Spectacular urbanization and accelerated inequalities

In Edinburgh, the government announced to invest 1.1 billion pounds into Edinburgh and its wider urban region in 2017. The main aims of this rather large investment are to improve transport infrastructure, housing, and data innovation centres. In addition, there is a 50 million pounds private investment in the district of Leith, which aims at constructing a student accommodation complex right in between the city centre and the harbour. At first sight, these developments seem to address the challenge Edinburgh is facing due to its prospected population growth very well, but there are some serious concerns about negative impacts of these investments. Locals fear that the investments do not aim at building affordable living space, but that they will rather transform a crucial part of the city into a luxury district with the aim of short-term profit.

Concerns about investments that do not target the average citizen are not ungrounded, as Edinburgh is the second most expensive city in the United Kingdom. These contemporary real estate developments contribute to affordability issues for average and low income groups in the city, which are often long-term residents of Edinburgh. One in five households in Edinburgh already lives in relative poverty. This inequality is unevenly distributed spatially among the different districts of Edinburgh: in the poorest parts of Edinburgh, not less than 27% live in relative poverty. At the same time, Edinburgh is Great Britain’s second largest financial centre, a status that is being boosted by eye-catching architectural projects. This is exemplified, for instance, by the new world-class concert hall that will soon open.

When looking at the average income level, Edinburgh belongs to the wealthiest cities in the UK but at the same time, poverty, social cleavages and exclusion are apparent. Only 1.4% of the children in Edinburgh’s poor areas have the grades that are demanded by top universities. That means that 98% of the children raised in these poor areas will not be able to go to one of the city’s prestigious educational institutions. The University of Edinburgh is ranked 29th in the global World University ranking and Edinburgh is home to the Roslin institute, a world-class medical research institute that is famous for being the birth site of the first clone of an adult mammal, Dolly the sheep.

Wealth and relative poverty are thus very close to one another within the city of Edinburgh. This inequality also seems to correspond to the political fragmentation in the city: in the poor neighbourhoods of Edinburgh, a majority voted to leave the European Union during the 2016 Brexit referendum, whereas in the richer neighbourhoods, the majority voted to remain. Another division arises between younger and older people: while younger people, who mainly have a low(er) income, are increasingly forced to move out of the city centre, the older and wealthier generations often have more means to stay. All in all, the already mentioned infrastructural projects will be quite determining in terms of how inclusive the future economic and demographic growth of the city will actually be.

Kuala Lumpur, too, is currently witnessing a number of large-scale infrastructural projects. Also here, critical voices have expressed concerns that relate to the inclusiveness and affordability of recent developments. For example, the district of Kampung Baru, which is located in the middle of the city, stands in contrast to the surrounding districts since it was not been developed into a business-centre with high-density residential and commercial skyscrapers yet. One of the reasons for this is that in the past, it was difficult for investors to buy the property because the Malay landowners were not willing to sell it. The ongoing population growth however motivates the Malaysian government to overcome the difficulties by investing heavily into the district. The Kampung Baru Detailed Development Master Plan was recently put into force, calling for the construction of 1,900 hotel rooms and 30 million square feet of office space.

Like many large-scale construction projects, the Kampung Baru development raised controversy among inhabitants, as it has frequently been questioned to what extent the project is going to benefit the average citizen. The Malay locals fear that their traditional, mostly agricultural way of living will be destroyed by the construction project. The government tries to tackle these fears by ensuring the locals that a few buildings will be preserved, and they will build a Malay heritage museum.

Financial sector based urban economies

To summarize my analysis up to this point, at first glance, Kuala Lumpur and Edinburgh seem to be very different with regard to their history, size and pace of development. However, when going into more empirical detail, it becomes apparent both cities have to deal with comparable concerns regarding inequality and exclusion that exist in the shadow of the glossy office buildings that accommodate the offices of transnational financial sector firms.

In Edinburgh, economic success for the city first and foremost means success for the high paid service jobs like the legal or financial services. This statement is supported by the statistic that 20% of the Gross Value Added (GVA) in Edinburgh originates from the finance and insurance sector. The GVA in this sector in Edinburgh already makes up half of the GVA in this sector in Scotland as a whole.

In Kuala Lumpur, similar phenomena can be observed. Just like Edinburgh, Kuala Lumpur is the region’s main financial centre, and economically most productive part of the country. Two main reasons behind Kuala Lumpur’s position of being a financial hub are its geographic location and the national government’s policies. Kuala Lumpur geographically is at the heart of, and thus centrally embedded within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Perhaps even more important, however, is that the Malaysian central government has put a lot of effort into establishing their country as a centre for Islamic finance. Islamic finance is unique in that it has to comply with the Sharia law and thus for example forbids speculation. The Malaysian government has built upon Islamic finance infrastructure during the past three decades and, in contrast to other states like Saudi-Arabia, has common state laws regulating the Islamic banks in the country. Today, the country is the world’s largest Shariah-compliant bond market.

It may be clear that both cities are quite well-connected to wider global financial networks, which has a clear impact on the socio-economic structure in both cities. In sharp contrast to the struggling non-wealthy groups within the society, there is a highly-skilled professional class that largely profits from this newly shaped urban economy. There namely seems to be a positive correlation between the size of the financial sector and the overall productivity of the urban economy, as well as with the average wealth of a city’s inhabitants. With a GVA of 39,300 dollars per year, Edinburgh is the second most productive city in the UK, while the income per household in Edinburgh (about 21,800 dollars) is higher than that in other major UK cities. The inhabitants of Kuala Lumpur were on average 67% more productive than the rest of Malaysia in terms of GVA. The average income of Kuala Lumpur residents is 70% higher than the income of the rest of the Malaysian population.

Conclusion

The conclusion of my comparison is that both cities, even if located on different sides of the globe, seem to depend on and profit from the presence of the financial sector, but at the same time, certain parts of the population experience the downsides of this economic structure, like for example costly housing or even displacement. Needless to say, these observations are still very explorative and tentative. Further investigation is needed in order to really understand the very (neoliberal?) policies that are at the heart of these developments, as well as the exact impact of the rise of the financial sector in both cities.