In search of Walking Space

TRRRING! ‘Get out of the way!’ A widely heard cry as a result of an insurmountable irritation among cyclists in Amsterdam. Where this irritation stems from? From either the wandering pedestrian, the inattentive tourist or the Amsterdammer walker. Amsterdam cyclists, as well as motorists, either complain about pedestrians structurally blocking the road, or the seemingly careless attitude of tourists jumping in front of cyclists. And to a certain extent, they have the very right to complain. Many times, pedestrians are indeed walking on everything but the designated sidewalk. Sidewalks are for pedestrians, streets are for cyclists and motorists. However, on the other hand, isn’t it very unfair to blame the pedestrian for walking on streets instead of sidewalks? When one looks critically to the way the Amsterdam streets are used and designed, one immediately realises that the streetscape is highly unbalanced. In June of this year, Het Parool and some other local blogs argued about the problems concerning pedestrians. The space for cars and cyclists is tremendous, whereas the sidewalks are sometimes non-existent, highly fragmented or blocked by parked cars, bicycles, scooters and goods stalled by the local shop. Given these factors, one can only come to the conclusion that every time a pedestrian walks on the street, it is an active search for walkable space, which, let’s face it, Amsterdam lacks.

Blocking Walkable Space on the Keizersgracht Amsterdam (source: maps.google)

Space of Parked Cars

The discussion about walkable space seems to get more attention within the Amsterdam government. In their infrastructure policy document ‘Accessible Inner City’ they state: ‘as a consequence of the traffic policies the public space is fragmented: streets are cut into separate lanes for cyclists, motorists and public transport, while pedestrians were not emphasised.[own translation]’ In other words: we didn’t give a damn about the people that walk. Given the fragmentation of the streetscape, the lack of walkable space seems to come as no surprise. What is surprisingly however is the fact that the discussion around more walkable space seems to be just loosely connected to the discussion about cars in the city. There are plans to largely reduce the amount of cars in the city centre; to further improve the air quality and foster more space for its inhabitants. With reducing the amount of cars, Amsterdam would follow the lead of the city of Helsinki, now outlining a plan to ban cars. And exactly that could be the solution for more walkable space. Take a critical look on the streetscape in Amsterdam, and one may realise how the streets are truly unbalanced: favouring the almighty car and neglecting the vulnerable pedestrian.

How to facilitate the flow of motorists, bicycles and pedestrians simultaneously? What are the options to improve the walkability and provide more space for the ones that need it the most? Let’s take one canal as prime example, the Keizersgracht (see picture above).

Current Canal Situation

The picture above underlines the concerns raised before: a tremendously slim (and fragmented) sidewalk, next to a fairly reasonable street. Taking these two aspects of the street into the equation, one will see that simply taking space of the street to widen the sidewalk is no option. Cyclists definitely will still have enough space, but cars certainly not. However, the discussion around cars is perhaps not so much about the cars that move, but about the cars that stand still. Every car that stands still occupies around 11 square metres, which equals an Amsterdam student room. A parking lot is generally 4,5 metres long and 2,4 metres wide. Looking at the streetscape Keizersgracht one can make the following picture: 1 metre for the sidewalk, 3,5 metres for the road and 4,5 metres for the parking lot. That simply means that of a total of 9 metres, only 11 per cent is reserved for the pedestrian, 38 per cent for cyclists/motorists and crazily enough 50 per cent (!) for the parked car. In other words, half of the available space is taken by a vehicle that no one uses. That seems odd. It certainly should raise questions to why cyclists and motorists are so actively attacking pedestrians who are looking for and are using space, whereas there seems to be no issue around having 50 per cent of the space ‘seized’ by a car not in use. After all, streets are essentially public space, and may be used by everyone. In this reasoning, the only thing that is actually intervening are the privately owned cars on the side of the canal. Okay, to be fair, they pay a tremendous amount of money to actually stand still there, but using this as an argument by only looking at public space as a tradable good, is too one-sided and only gives room for even more unbalanced space.

Walkable Amsterdam Canal – Green Strip (Source: Louise de Hullu)

Amsterdam canals: liveable and walkable

This argument opens up new ways of thinking about the current state of Amsterdam’s streetscape. It gives room to questions as to what can be done with the space of parking lots. If one envisions a street that is usable for everyone, and should facilitate the different meanings a street could have – such as providing space for people that walk the city – it could be insightful to actually step away from the words and show what is possible. As an engaged and critical architect, Louise de Hullu has made two clear scenarios of a canal that is accessible for everyone and gives room for new understandings of how one looks at the street and what usages are actually possible, by simply rethinking of what occupies the street.

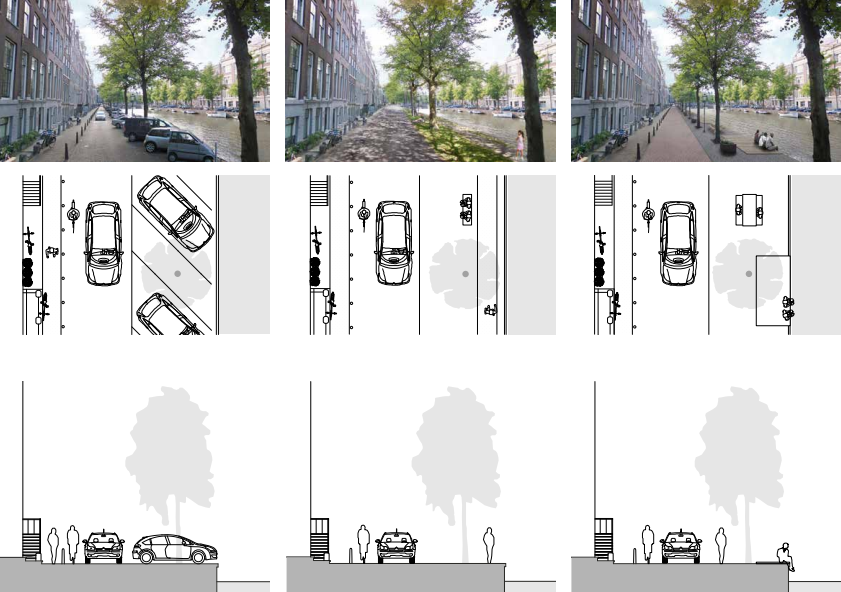

Different scenario’s for a walkable canal: (1) current situation, (2) green strip, (3) boulevard (Source: Louise de Hullu)

Green Strip and Boulevard

The above scenarios provide us with some insight into what is possible on the Amsterdam canal. The space occupied by parked cars is such a vast amount of space that could be used otherwise. Thinking of a green strip as urban green that not only improves the space to walk and the enjoyment the city, it might also improve the air quality, reduce hot temperatures, and improve public health. Alongside the possibilities for walkable space, the boulevard scenario show us new ways of connecting to the waterfront and the view of the 17th century houses on the other side of the canal, otherwise blocked by the cars in the current situation.

Walkable Amsterdam Canal – Urban Boulevard (Source: Louise de Hullu)

For whom is the street? What can be done with the current space occupied by vehicles that do not move? Who are we blaming now for using the roads? If we would think more critically about what we have right now and what would be desirable in the future one provides ways to incorporate creative ideas that might seem currently far-fetched but reasonable in a couple of decades. Whenever a cyclist is shouting or a driver is horning to clear the streets from annoying pedestrians, one might actually think of the pedestrian’s position in a city that is walkable in terms of distances, but not in terms of available space.