In the last moments of t-shirt weather, get outside and do a little people watching. Pay particular attention to bare skin: especially exposed calves, shoulders and upper arms. What do you see? Ink, ink, everywhere, ink. These days, everybody seems to have a tattoo. What was once a practice in Western society reserved for soldiers and subaltern groups like bikers, circus performers and ex-cons, tattooing is now securely mainstream. It’s a curious practice: a permanent commitment to a single statement. Whether it’s a sweetheart’s name or favourite flower, as soon as the needle hits the skin, there’s no turning back. Regrets be damned.

The classic triple X Amsterdammer tattoo (Photo: FaceMePLS)

So why do we do it?

We very easily see the fault in others’ tattoos. Is there really a good, lasting, defense for our younger cousin’s Y.O.L.O tattoo? Are we really expected to keep a straight face while our neighbour explains, “Pace means ‘peace’ in Italian, which basically sums up my personal philosophy”? But while we may see the ridiculousness of a youthful indiscretion forever stamped across a kid’s chest, or feel uncomfortable with the earnestness of a sincere personal statement plastered on a forearm, we’re no better than those we criticize: we’re doing it, too. More than ever in modern Western history. But somehow we trick ourselves into believing that our tattoos are not silly, that they really are meaningful. So what makes us enter the tattoo parlour and throw down cash for possibly one of the biggest mistakes of our lives? A decision that we’ll be faced with every time we look in the mirror. A choice we’ll have to unabashedly justify every time another person sees our ‘work’ for the first time.

If you’re in Amsterdam, look for the X X X.

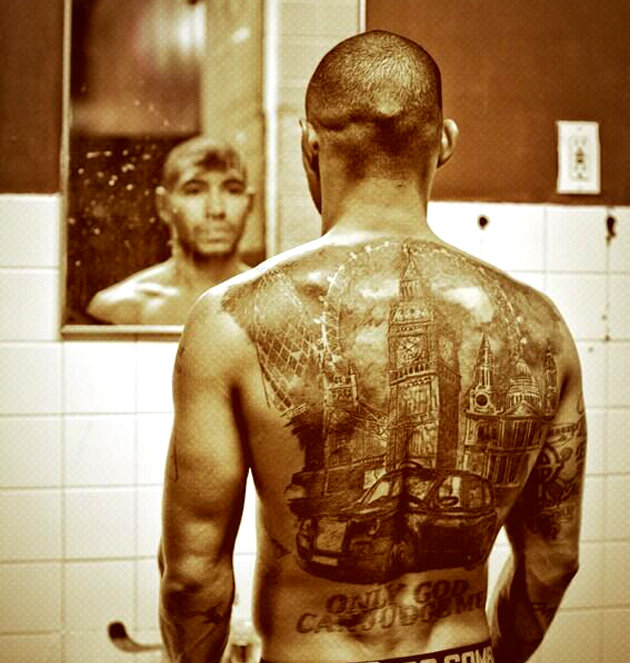

Opinion aside, two facts about tattoos: they hurt; and they’re permanent. If we assume most people put at least 30 seconds of thought into a tattoo choice, can we glean any significance from the preponderance of triple Xs that appear when the weather’s nice in Amsterdam? If tattoos really do serve as markers of self-identity, what does it say that city-specific–rather than regional or national–tattoos are popping up everywhere. Why are residents of major cities identifying with the city to such a devotional extreme? Why does an Amsterdammer commit to to three white Xs, or a Londoner to Big Ben ?

London’s Big Ben British boxer Theophane (Photo: Twitter – @AshleyTheophane)

The city tattoo seems to say something very different from the patriotic tats of old. Counterintuitively, jumping on the American eagle, Union Jack or Canadian maple leaf bandwagon seems passé and provincial, while sporting local insignia seems to hold some cultural cachet. Sure, it makes sense that as the nation-state wanes under the pressure of globalization, we see through the social-constructedness of nationality, and maybe we don’t feel the urge to endure a thousand pin pricks just to prove something just as easily demonstrated by whipping out our passports. But then why do we need to brand ourselves with our local area code or subway map? This presents us with a strange paradox: in this age of global flows we’re supposed to be more mobile, more mutable, more cosmopolitan; yet through city tattooing, we quite permanently anchor ourselves to hyper-local identities.

Markers of Individuality?

While it’s impossible to give a single explanation that justifies every skyline, bridge or city map tattoo strolling down our city streets these days, if we watch closely, we see patterns emerging. A city tattoo iconography is developing. Image search the name of a favourite city, along with the word ‘tattoo,’ and certain preferred representations will dominate the results. Confoundingly, despite the repetitiveness of these pictorial representations, tattooees still inscribe them with individual meaning.

Chicago ‘L’- map (Photo: Kaliptikal Magazine)

The Body, the Self, and Society

In very literal terms, skin is the material boundary between the self and society. A Foucauldian reading interprets tattoos as the self re-appropriating the docile body hijacked by the state. Tattooing is an act of resistance against cultural forces that commodify the body. But if we use tattooing to re-assert our individuality, why would we brand ourselves with city logos, insignia of our hijacker? Are we suffering from a case of Stockholm syndrome? Perhaps something else is going on.

Sociologists such as Jill A. Fisher identify four primary and overlapping functions of Western tattooing: as a ritual act to create milestones in a culture where so few rites of passage remain; as a decorative form of exhibitionism; as a protection, a sort of contemporary talisman; and finally, as an identification, to signal belonging in a group (2002, p.100-101). This final function is particularly relevant to city tattoos. Authors such as Orend & Gagné (2009) argue that with the increasing fragmentation of contemporary Western society, we purchase tattoos as cultural products for ‘personal identity projects.’ In our consumer culture, we buy our way into belonging, and with their lifetime warranty, tattoos are especially reassuring.

I would suggest that city tattoos perform a unique dualistic role in self-identification under conditions of glocalization. Although in detail, these tattoos manifest themselves as hyper-local, they simultaneously speak a global visual language that places the bearer within a global ‘urbanite’ group identity. A Berliner, a Seoulite, a Torontonian, and a Seattleite may commit to tattoos of their home city’s iconic tower; however, these tattoos defy local boundedness when read as a commitment rite to urban life. When viewed from afar, these tattoos blur into an indistinguishable general form. Does the same hold true for the urbanite with the tattoo? If a tower is a tower is a tower, is an urbanite is an urbanite is an urbanite?