The Death and Life of a Laotian City

Vang Vieng. With 30.000 inhabitants the 8th largest city of Laos, situated in a stunningly beautiful valley, directly at the Nam Song River, surrounded by a picturesque karst hill landscape. Perhaps relatively unknown by the average urbanist, though since a couple of years very famous among young, hedonistic backpacking tourists. After some years of rapid expansion in a somewhat anarchistic way, the ruling socialist party of Laos recently pulled on the handbrake deciding to shoot down its main attraction. In this article, I will describe the sudden rise, as well as the current uncertain future of Vang Vieng: Southeast Asia’s contested party capital.

It is quite clear that the perception of urbanity can differ enormously, depending on local or national context. In Laos, the most sparsely populated and underdeveloped country of the wider region (formerly known as Indochina), even small human settlements with at least a permanent market, electricity, piped water, and some decent road access can almost be regarded as leading urban centres. Although there have been some clear patterns of urbanisation during the past few decades, the Laotian capital Vientiane is still a serene oasis compared to neighbouring capitals as Hanoi, Bangkok or Phnom Penh. While most of the urbanisation processes are stimulated by timber or forestry industry or trade opportunities alongside the Vietnamese border, another main catalyst has been the increase of tourism. And, in the case of Vang Vieng, a very specific, controversial type of tourism.

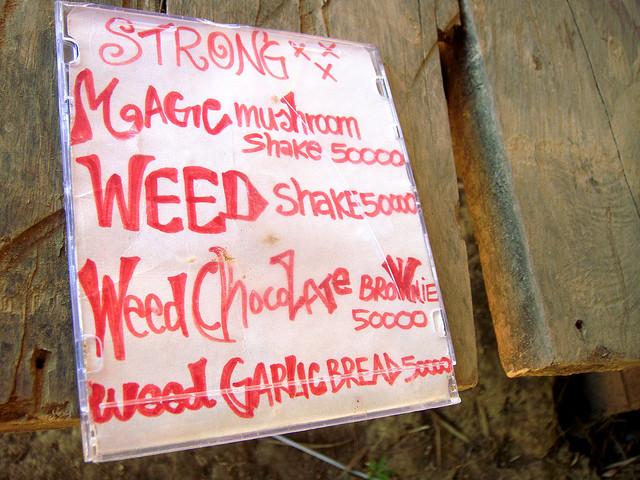

Still at the beginning of the new millennium, Vang Vieng was nothing more than a quiet village where rice farming and fishing counted as the main sources of income for the local residents. This setting radically changed when about 10 years ago, as a number of both Laotian as foreign entrepreneurs decided to set up a new event which ought to make Vang Vieng Laos’ backpackers capital. This event, which soon got famous by the name ‘tubing’, consisted of a simple but successful concept: people could rent a ‘tube’ (the inner tier of a tractor) at a depot in the centre of the town, after which they were driven a couple of kilometres up the river to a spot where they could enter the water of the Nam Song. Along the banks of the river, there were numerous bars including swings, ziplines and slides, as well as music, several games like beerpong or mud wrestling and, last but not least, dirt-cheap buckets (!) of locally brewed whisky, the so-called ‘Lao-Lao’. After the tubing, one had a variety of options to continue the party downtown: where many chose to enjoy a couple more drinks at one of the bars, the more adventurous visitors were happy experimenting with some locally harvested drugs, varying from marijuana to opium and from mushrooms to ‘jabba’, all even more easily obtainable than in Amsterdam, and, in case the customer desired, possible in a nice combo with for instance a milkshake or a pizza. After 11ish, nearly everyone went down to an island located in the river again, where the party often lasted almost until the new round of tubing started up again the next morning.

Clash of cultures? (Photo: Matthew Bennett)

Drug availability in Vang Vieng (Photo: jonrawlinson)

Meanwhile, as the popularity of the place rose, so did its amount of criticism. First of all, the tubing tourists were accused of not having the slightest bit of respect for the culture, and the behavioural norms and values of the local community. It is indeed quite a remarkable spectacle in Vang Vieng, when young Buddhist monks are passing by one of the downtown bars where hungover tourists are, sometimes scantily clad, sleeping off their intoxication, while getting a glimpse of the permanently showed TV series like Friends or Family Guy every once in a while. It is thus conceivable to some extent that local conservative Buddhist parents do not regard most of the backpackers as the most decent role models for their growing kids.

Enthusiastic tuber on the zipline (Photo: jonrawlinson)

Second, with the increasing number of visitors and the increasing number of bars, also the number of fatal incidents shockingly increased. Although the exact number of deaths seems to be unclear, it is a fact that nearly every week, one or more tubers got seriously injured, albeit as a result of excessive alcohol or drug abuse or just due to a bad landing after an overambitious attempt to achieve a graceful dismount of one of the trapeze swings. Once again, due to a complete lack of authorities or any responsible organisations, people generally did hardly bother at all and just continued on doing their day-to-day businesses.

Tubing down the Nam Song River in Vang Vieng, by lawtonjm (Flickr)

Then, just recently, the, according to some almost inevitable moment came that the Laotian government ultimately decided that enough was enough. Within a couple of weeks, all the riverside bars were demolished, as well as the ones on the earlier mentioned island, and suddenly the former party capital of Indochina became a sort of spooky-town: a number of bars were forced to close down their doors, while many of the recently established hotels and guesthouses remained empty. While the main criticasters and the more conservative locals have probably welcomed those radical and harsh measures, obviously not everyone has been that enthusiastic about it. Apart from the party-minded backpackers and the local entrepreneurs, there have also been local Laotians who asserted that quality of life increased since the arrival of the tubing: working in the tourist industry was by them regarded to be much more attractive compared to the rice fields, while it has also been argued that education opportunities for children improved during the last couple of years.

Today, the future of the city is still quite unclear (video). Since the scenery is still there, it is likely that the city will try to remain a tourist destination, though aiming to attract a different, perhaps less contested group of tourists in the near future. Although it might take a while before the city manages to change its dubious image, this scenario is probably most desirable for the majority of the people. Or will the city nonetheless survive as a crazy party place, just with some additional extra safety measures? It is anyhow unlikely that Vang Vieng, in the currently urbanising Laos, will return to what it was not so long ago: a remote community village existing of peasants and fishermen.

Whatever the future might bring, there are plenty of videos on Youtube that will remind us to how extraordinary the 8th largest city of Laos once used to be.