Leipzig’s urban development has certainly seen its highs and lows since the end of the eighties. Just as much has the reputation of the city been under constant change. Both were heavily affected by the war and forty years of communist politics. The city has been named ‘Heldenstadt’, ‘Hypezig’ or praised as regional economic center, but headlines denouncing Leipzig ‘capital of vacancy’ and the weekly demonstrations from the rightwing Legida movement have also shaped Leipzig’s (inter)national reputation. Since the turn of the century the city seems to have taken a take-off and has been granted with a lot of international attention and praisings. Whilst celebrating the recent economic successes, in which the new image as a post-industrial, creative metropolis could take shape, the city has been on the search for her new identity. The bigger part of this identity was not constructed by strategy, but rather the result of unplanned coincidence.

Cautious City Development

After the collapse of the GDR, Leipzig was left in chaos and new guidelines needed to be set out to give direction to the future of the city. In January 1990, just months after the ‘Mauerfall’, citizens, urban developers, and others gathered at the Volksbaukonferenz (People’s Building Conference) and discussed the future of Leipzig. At the Conference the anticipated arrival of western investors was now seen as the biggest threat for the coming years. In popular voice this threat was figuratively labeled as ´the third city destruction´, after the war and the GDR had left their respective traces. Still, destruction was kept relatively low compared to the West. Therefore Leipzig had one the highest amounts of Gründerzeit (late 19th century) monuments in Germany, but their situation was rather critical. The most urgent goal of the Conference was the call for a building stop, to prevent westerners from playing before the rules of the game were explained. These rules were discussed at the conference and exhibitions were set up by citizens and experts.

Exhibition in 1990 organized to raise debate on the future of the city. Source: Pro Leipzig.

The ideas mostly centered on the concept of ‘modest city development’, based on the ‘Internationale Bauausstellung‘ (IBA) [PDF] previously held in Berlin, 1987. Modernist urban development was then tabooed, citizen-participation put to the fore. Demolitions should ideally be reduced to a minimum, original home plans were set as example for the restorations of the old buildings, and ‘critical reconstruction’, focusing on the revival of old neighborhood structures, the parole. The building stop demanded by the Volksbaukonferenz didn’t sort much effect by itself, but a different issue came apparent that did frustrate the investors. Decades of communist politics had left Leipzig with a lot of unresolved questions of ownership. A significant deal had to be taken to trial, until the current day posing problems for city developers in carrying out their plans. Therefore not so much the success of the Volksbaukonferenz, but rather this very practical problem forced developers to move out to the surroundings of Leipzig, resulting in a huge growth in shopping centers and office spaces in the suburb areas. After a few years, though, also in Leipzig slow but sure the building stop proved to be untenable.

Perforated City

At the end of the nineties, in retrospect, the fears posed at the conference turned out to be justified. A million m2 newly built office space soon came vacant up to an 80% rate, multiple shopping malls filled the small historic center, and 30.000 new homes were established, while at the same time the population was decreasing. False optimism as well as the neglect of the existing monumental buildings posed huge problems, not only in Leipzig. As in more former GDR-cities demographic challenges were becoming apparent, the BRD decided in 2002 to introduce a program that focused on creating a new balance between demography and the existing housing stock. In Eastern Germany vacancy had triggered huge social problems, and with an investment of 2.7 billion Euros from 2002 to 2008 the government aimed at stabilizing these regions. The regions and cities could for the most part invent their own policy, but subsidies were granted for demolishment which actually stimulated housing corporations to tear down instead of preserving. According to Leipzig researcher and art-historian Arnold Bartetzky 1300 monuments were torn down between 2001 and 2004, which, with some more effort, could have been saved. The program therefore clearly was a bad incentive for the heritage movement, already pointing out the dangerous and bad condition of about 50% of the monuments during the Volksbaukonferenz.

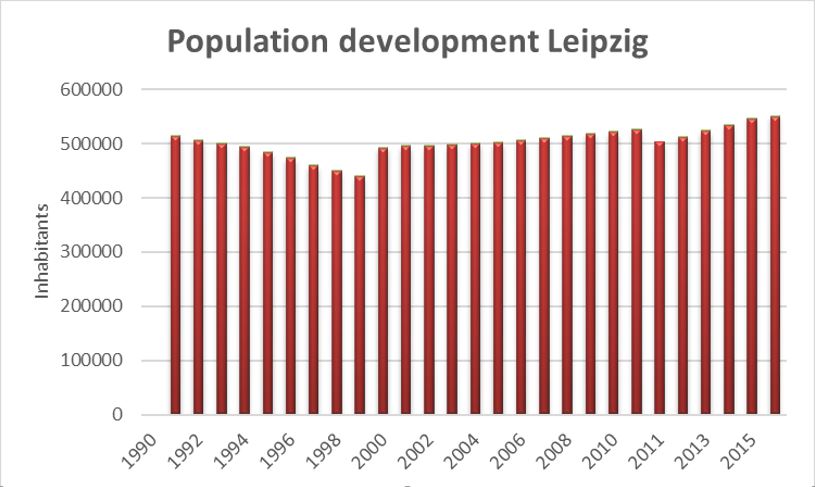

Paradoxically, as the program was laid out, Leipzig was starting to grow again. From 2001 onwards, the city had seen an annual growth of about 10.000 people per year, now for the first time in decades. The combination of new, young people coming to the city and the availability of cheap space made Leipzig an interesting place to settle, with lots of opportunities for students and artists. While this process was taking off, the Leipzig urban planner Engelbert Lütke Daldrup laid out his designs for the new city. In his view, post-industrial and post-GDR cities like Leipzig could be conceptualized as ‘perforated cities’. Mostly because of the lack of restorations during GDR-times, large empty spaces in the streets were reminders of the tempestuous history. His approach of using the empty spaces as parks and free spaces functioned as a major aspect of his design to make the city more livable. Former empty areas were redesigned into parks, neglected buildings now demolished. The economic idea behind it focused on bringing supply and demand closer together, he planned to demolish 7500 housing units, of which 700 monumental buildings. This system of demolishment was euphemistically called ‘Rückbau’, implying rather the return to a given original state than the factual drastic demolishment of large amounts of buildings.

Source: Statistisches Landesamt des Freistaates Sachsen. In 2000 administrative changes accounted for the increase, in 2011 new census information led to a correction.

To explain the background of these plans, it is important to understand that even in 2004 policymakers still believed that the city would shrink rather than grow. Social problems were huge in the western and eastern districts as well as in the ‘Plattenbau’-area of Grünau. The growth of the city was then imagined as divergently developing in two directions. In the center growth was visible, in the periphery decline still threatening social order. And also today, demolishment as well as revaluation is still necessary in some of these areas to retain social balances. This reality, in which population growth existed next to large vacancies in the peripheral areas, offered less-well-off income groups opportunities to settle in the area. Privately organized initiatives to redevelop industrial areas such as the Spinnerei Factory originated in these years.

An example of a Haushalten project, in the Leipziger Westen. The ‘Ausbauhaus’ concept is an exchange of the long-term resident investing in the building for a relatively low rent. Source: Daniël Kipp.

The citizens’ initiative Haushalten e.V. offered opportunities to artists and students with social or cultural ideas to settle in neglected buildings (comparable to the Amsterdam ‘Broedplaatsenbeleid‘ in present day). Helping overcome bureaucratic troubles, residents were upgrading these buildings for later redevelopment purposes in return. This way Leipzig slowly developed bottom up, while the city government was mostly occupied with providing the secondary and tertiary sector the infrastructural incentives that in the long run helped Leipzig settle as promising post-industrial economy.

Unplanned City Planning

Economic reality shaped Leipzig’s urban development in the nineties, leaving the existing housing stock in neglect, while the turn of the century announced the development of Leipzig into a livable and welcoming culturally diverse regional metropolis. Not much of this was planned; prognoses of population decrease had influenced most of the plans up to 2004. From the bottom up a new reality was by then already taking shape, leaving young people with a lot of space to collect and spread new ideas. Leipzig today is not so much the result of strategic city planning, but rather a coincidental series of events and failed investments, an insight that planners nowadays should eagerly bear in mind.