“Most of the younger ones are just interested in fighting […] It’s quite pathetic I think. It’s just an area, apart from that we’re just the same, so why fighting over an area?” Said Neil* (19), one of the ‘Possilpark’ respondents from my research in which I qualitatively investigated the relation between territoriality and social exclusion among youngsters in disadvantaged areas. A couple of months after the occurrence of our interview, Neil got randomly attacked by a number of young boys when he was walking down a street in an adjacent (rivalry) area on his own. Luckily, his stab wounds recovered reasonably fast so he was soon allowed to leave the hospital.

Saracen Street December 2012, Possilpark

Glasgow has been suffering from the image of being a violent city for many decades: sectarianism, gang formation and knife crime are issues the city has seriously had to deal with for over a 100 years. And although this latter issue seems to be improving to some extent, the city still has the highest rates of homicides and violent crime within the entire United Kingdom. In this article I will position the issue of territoriality within the current academic debate on ‘neighbourhood effects’ and social exclusion, while reporting the most interesting findings from my case study in Possilpark.

‘Too much cohesion’

One of the most discussed global social-cultural trends since the beginning of the 21st century is – without a doubt – individualisation. It has been considered as a new social structure, and even as a fate rather than a choice. Traditional institutions such as the family, the church or the labour union have often lost their strong hold on the individual. One of the on-going debates directly related to individualisation is the one about decreasing social cohesion. In the field of urban studies, it has been argued that the neighbourhood has eroded as a source of social identity, and that particularly disadvantaged urban areas are nowadays often characterised by mutual feelings of distrust and fear, which tends to result in increased social isolation of individuals. Others assert the opposite; they argue that in fact family ties, mutual aid and collective efficacy are still likely to be found in (especially) homogeneous deprived areas today.

Even though the ‘loss of social cohesion’ in a neighbourhood is undisputedly considered as a negative development, Kintrea and Suzuki (2008) are stating somewhat provocatively that ‘too much cohesion’ can also be regarded as a potential societal problem. Hereby, they are thus referring to the persistent feature of territoriality among young people in Britain’s deprived urban areas, and how this possibly impacts their opportunities in life. According to them, territoriality is a form of cohesive behaviour that has not been shaken off by social change. In this particular context, territoriality can be defined as “a claim over an identified geographical space, which is defended against others” (p.200) and as a form of “hyper place attachment, which builds directly from young people’s close identification with their neighbourhoods” (p. 461). The negative consequences of this phenomenon subsequently seem to outweigh the positive ones, which I will illustrate by my research done in Possilpark.

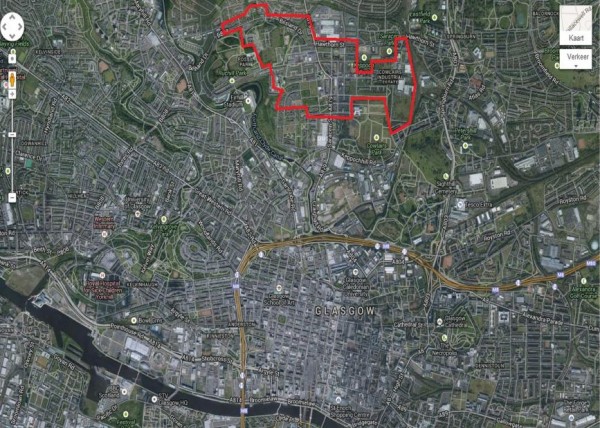

North Glasgow’s stigmatised Jungle

Possilpark is a neighbourhood, or ‘scheme,’ as the locals would call it, in the north of Glasgow. The area was mainly realised by the ‘Saracen Foundry’ in order to accommodate its workforce near by. After its closure in 1967, unemployment rates in the area rose severely . From that moment onwards, it has been a neighbourhood that has proved to be heavily stigmatised as being an unsafe place, and a centre of drug dealing, while it is ranked highly within the first decile of the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation. Moreover, the physical condition of the area does not immediately help to improve this negative image: although the houses within the area are not necessarily of bad quality, public spaces within the area look relatively deprived. One can find a large amount of derelict land within the area, as well as badly-maintained buildings with broken windows.

Broken windows and derelict public space, Possilpark

The severe stigma of Possilpark was something all the youngsters that I talked to were very much aware of. While most of them were rather indifferent about it, stating things like “I’m not bothered, I know it is not true”, it seems that a significant group from ‘Possil’ – especially the earlier referred to ‘younger-ones’ – embraces and glorifies the rough image of their scheme. This image is mainly inherited from the 1980s, when (a part of) the area got the nickname ‘The Jungle’. One of the youth workers I spoke to noticed that some young people want to maintain their family reputation and try to be like their dads or uncles used to be back then. Another youth worker also recognised that there is a group of youngsters that is rather proud of the rough image of Possilpark: “They’re proud to say ‘I’m from Possil, I’m a Possil boy’. They’ve changed their accent, they’ve changed their voice. They’re thinking about their selves as being a hard man.” Hence, as Kintrea et al (2010) also found out already, it are mainly boys between 13 and 17 years old whose lives got more or less determined by territoriality.

Isolated by imaginable walls

As the first paragraph of this article already illustrated, exposure to violence for youngsters from Possilpark is rather common. It seems to be nearly impossible for them to entirely stay away from territorial issues, even for those who clearly distance themselves from rivalries and its associated territorial gang behaviour. A majority of youngsters from the earlier mentioned age category tends to regard their own scheme as a safe haven; they are too afraid to pass the invisible boundaries unless they are in a big group. This fact is – logically – strongly interrelated with ‘mechanisms’ that are often referred to by scholars investigating ‘neighbourhood effects’, which for many years already forms a hot topic among urban geographers.

One of those ‘mechanisms’ concerns the key role of social networks. A common hypothesis is that young people in homogeneous deprived neighbourhoods often have less dispersed, and less diverse social networks. This is thus regarded as being potentially problematic: “social inclusion depends on links to more advantaged, mainstream groups and thereby to networks offering critical information, material support or moral/cultural examples, which are rendered more difficult by spatial segregation from these groups” (Buck, 2001: p. 2255). Almost without any exception, all the respondents that I talked to during my research indeed indicated that they had hardly any friends living outside ‘Possil’. Territoriality certainly is a limiting factor in this which should not be underestimated. One of the coaches of the Possilpark football team exemplifies this by stating: “One day I was trying to get a couple of the guys from Woodside which is in George’s Cross, to play for the Possil team, and then some of the boys said they didn’t want to walk up here, in case they would get more or less beaten up on their way up. So they couldn’t really walk into another area without having a fight or something…”.

Apart from their ‘social’ mobility, their spatial mobility, or ‘daily paths’, are also clearly affected by territoriality. As a result of this, the level of participation of the Possilpark youth with activities organised elsewhere in the city leaves much to be desired. This is contributing to a certain level of social exclusion. This is illustrated by another youth worker, who, when she was asked which facility she thought Possilpark was missing mostly, responded: “I would say ehm.. a big sports centre.. There’s something down the road, but it doesn’t have a swimming… If they want to go swimming they need to go to Springburn, which isn’t that far, but I know young boys that won’t go swimming in Springburn, because of the territorial issues.. They think if they go there they might get bother, and all that.” […] “I mean that’s not the reason to build a swimming here you know. But something like that, young people are affected by.. you know they may not be able to use this kind of facilities elsewhere because of these reasons.”

Territoriality, neighbourhood effects and social exclusion: a reciprocal relationship?

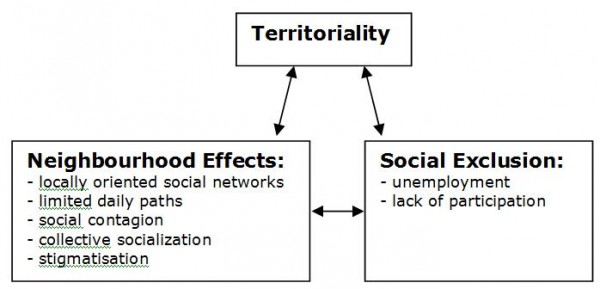

From the findings of my research it thus seems that territoriality definitely has a significant impact on the lives and social perspectives of young people from Possilpark. It seems that territoriality within disadvantaged neighbourhoods is having a reciprocal relationship with a number of assumed mechanisms regarding neighbourhood effects, as well as with social exclusion-indicators. Apart from the given examples about one-sided social networks and limited daily paths, one could also think of ‘social contagion’, in the form of mutual peer pressure, and ‘collective socialization’, in the form of common norms, values and identities. Stigmatisation, which is often mentioned as an ‘external’ neighbourhood effect, can be added to this list as well.

Scheme made by author

Whether territoriality is likely to be an expected issue within a particular neighbourhood is not easy to predict. Apart from the relationship between territoriality and neighbourhood disadvantage there are many context-dependent factors that are likely to play a role as well, including inherited images from the past, or potential ethnic or sectarian tensions. Future research on territoriality should keep investigating which factors are determinant in this sense. Furthermore, the impact of territoriality is difficult to compare across borders. Here, I would like to hypothesise that different ways in which welfare states are organised play a decisive role. Structural political factors may be key to the solution of tackling this issue.

For neighbourhoods as Possilpark, policy makers should in the meantime be aware of the fact that territoriality is a societal problem which is not to be underestimated. It is very important to signal and avoid it where possible. In that sense, charity organisations as A&M Training and YPF are doing a wonderful job in their attempts to tackle this persistent problem.

*This is a fictitious name as all respondents were promised to remain anonymous

All pictures are taken by the author