Behind the former Iron Curtain, on the southern Black Sea coast of Bulgaria, lies the legendary resort of Sunny Beach. Carefully built from scratch as an upmarket playground for the Eastern Bloc elite during state socialism, the relentlessly urbanized coastal resort now is an ultimate tourist dream destination for package holidaymakers. Based on my employment in the mass tourism industry in Sunny Beach seven years ago and my fieldwork about wild beach conservation on the Black Sea coast last year, I will try to show you how the urban transformation of the biggest Bulgarian seaside resort is embedded in the dreams of planners, governors, investors, tourists and workers.

Strict centrally planned resort

The construction of the holiday complex Sunny Beach started in 1958 following the communist party’s ambition to develop the natural resources of sun, sea and sandy beaches along the Bulgarian 380-kilometer coastline into an all-round and neatly packaged tourist product and to market it to both domestic and foreign holidaymakers. A team of architects, urban planners and engineers at Glavproekt, the central state institute for architecture and spatial planning, designed the resort. The crescent-shaped bay with soft sand dunes became a testing ground for the renewal of resolutely modern design that rejected the former Stalin’s Neoclassical Revival style.

From social tourism to mass tourism

Sunny Beach was conceived as a family resort embedded in greenery offering nature-based social tourism, which was essential to the communist ideology. Interestingly, this type of social tourism—subsidized holidays for workers—evolved progressively and gradually during the following decades into mass tourism. This process reflected directly into the architecture, both in terms of enlarged capacity and diversification of the different types of accommodations.

A remnant of the socialist modern architecture (Photo: author)

Socialist modernism and consumer services

Playful themed architecture, ranging from hotel towers to low-rise hotels and bungalows resembling rural homes, was complemented by booming gastronomy and entertainment options, such as restaurants, bars, folk taverns, fantasy worlds, casinos, mini golf courses and mildly salacious stage acts. The resort displayed the latest achievements of the internationally acclaimed Bulgarian architecture at that time. The architectural design and services subconsciously reminded the common workers that they could not escape the communist ideology even during their holiday.

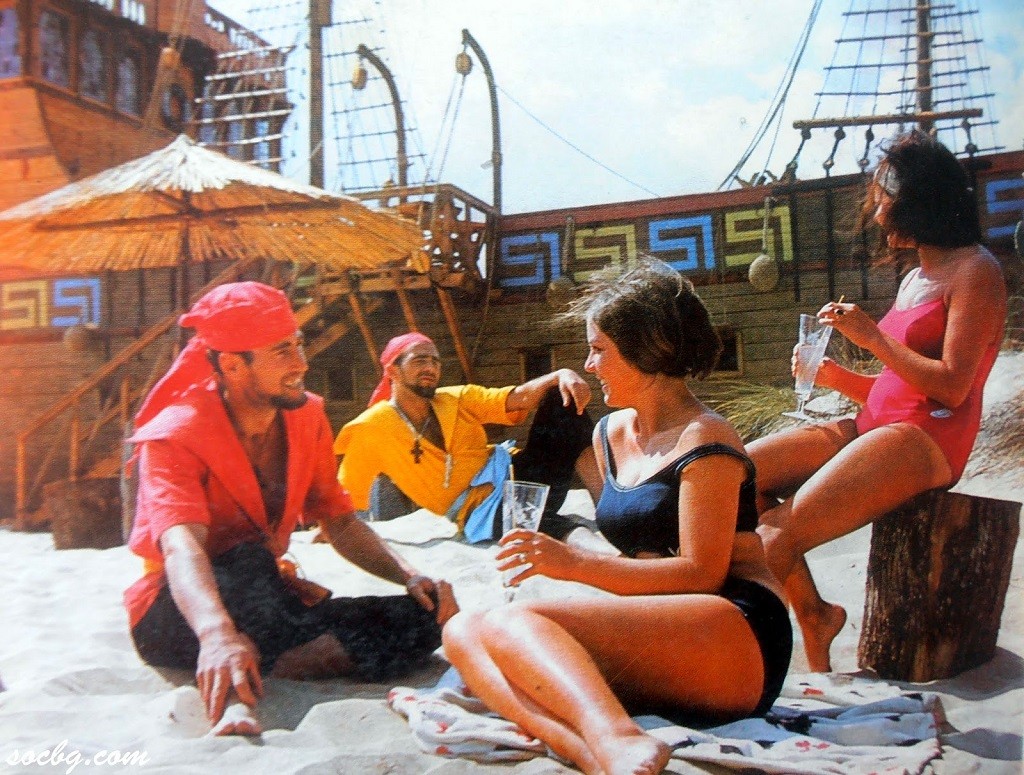

The emblematic pirate ship Fregata burned in 2013. Picture from 1966 (Photo: socbg.com)

Synthesis between capitalist practices and socialist premises

The late-modern leisure landscape of Sunny Beach was the result of a synthesis between the socialist ideology and western commercial tourist model. This peculiar synthesis was a necessary condition for Bulgaria to meet the criteria of economy of scale, especially when the country wanted to sell its most precious and exclusive commodities, such as tobacco, cognac, chocolate, vegetables and fruits. Moreover, the Zhivkov government realized the need to channel hard currency to Bulgaria via its resorts in order to bail out the country from the severe oil crisis in the 1970s. Playing its active role in East-West competition, Bulgaria kept its citizens in check and welcomed foreign holidaymakers from both sides of the Iron curtain to impress them with the socialist progress on display in Sunny Beach.

The end of the resort’s socialist glory

In the 1980s, the construction of the resort stopped due to the exhaustion of its capacity. From 1959 to 1989 Sunny Beach was visited by over 5 million international and over 2 million domestic holidaymakers. In 1989, when Sunny Beach celebrated its 30th anniversary, the resort had 108 hotels with more than 27 000 beds, 130 restaurants as well as many consumer amenities. Sunny Beach was the visiting card of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria and a rival of many resorts on the Mediterranean Riviera.

Halting privatization and regulations

The privatization of formerly nationalized assets in Sunny Beach followed the political and socio-economic upheavals after the disintegration of state socialism. To ease its privatization, the resort was broken down into smaller units before mass privatization took quickly over in 1997. The rapid change of governance and administration in all levels in Bulgaria allowed multiple amendments of the construction parameters. In the end, the regulation law was delayed and when it came into force, it was too late.

Construction boom and bust

After several years of stagnation and halting privatization, an investment and construction boom occurred at the turn of the millennium. British and Irish real estate investors dominated the first years of the construction boom and especially after Bulgaria’s accession to the EU in 2007. When the global economic crisis hit Bulgaria, the real estate market in Sunny Beach bust. Attracted by the consequent cheap prices of holiday homes, preferably seafront properties, Russian-speaking citizens rediscovered Sunny Beach as one of their favorite travel destination from the communist era. However, the EU’s sanctions against Russia over the Ukraine crisis lead to an outflow of Russian buyers and holidaymakers. Nowadays, vacant properties are awaiting their new owner.

Mafia Baroque and anthropogenic hazards

The veritable bonanza of speculative property development ate up the remaining free and green spaces. The face of Sunny Beach and its architecture changed radically. Old hotels were enlarged and many other buildings were demolished to free space for bigger constructions.

The Golden Orpheus’ scene became the first mall (Photo: socbg.com / author)

New architectural style known as Mafia Baroque marked the rejection of socialist modernism (minimalist, functional and coherent) with garishness appeal for attention, kitsch and purposeful excess. Some of the elements that constitute it include cupolas, Corinthian columns, porticos, mansard roofs, marble panels, mirrored glass, all of which can be combined in one structure. This style epitomized the status anxiety of the new neoliberal society and the rise of organized crime in the 1990s.

Mafia Baroque built et manse on Bulgaria’s coast (Photo: Stoyan Todorov)

Urban sprawl, monopoly, population increase (both local residents and tourists), inadequate infrastructure (sewage, plumbing and electricity), questionable quality of constructions and services put steadily pressure on small-scale local businesses, coastal sustainability and safety in Sunny Beach as well as overall on the Bulgarian seaside.

A disenchanted world?

The images and perceptions of Sunny Beach have shifted from era to era, from the strictly planned resort of the late 1950s through to the 1970s mass tourist resort, from halting privatization to the outcomes of the construction boom and bust at the beginning of the twentieth century. This change of the tourist product has put many colors to the everyday life experiences of individuals involved in the tourist sector.

Undoubtedly, the construction booms before and after the fall of socialism created jobs in both tourist and construction sector as well as increased gross revenue. However, the spatial limits and environmental hazards urged the Bulgarian society to demand from investors and politicians to adjust their marketing strategies to keep the industry thriving. Contrary to popular beliefs, the gendered organization of the tourist sector during socialism helped women adapt later to the market economy on the coast. Kristen Ghodsee documented the personal stories of how several Bulgarian women accomplished their career dream on the seaside.

- Sunny Beach Panorama 1970s

- Bar Variete, 1968

- Bulgarian export cigarettes

- Golden Orpheus – international song festival

- Sunny beach panorama in 21st century

- Consumer culture, 2014

All pictures in this Gallery are from www.socbg.com except the last one which is the author’s

Interestingly, the all-inclusive formula in the post-socialist period was in a way a projection of the communist’s vision of all-round and neatly packaged tourist product that included an accommodation and three meals a day. The all-inclusive tourists, surrounded by eye-catching Las Vegas-style architecture and numerous amenities, replaced the international high-end holidaymakers from socialism. In this seaside Disneyland, tourists find discrepancies between the holiday advertisements and services. As depicted in several TV programs, European youth prefers Sunny Beach, similarly to Kavos, Lloret de Mar, Ayia Napa, Magaluf, or Ibiza as a hedonic party destination, which is full of binge drinking, promiscuous sex, life-endangering events, peculiar work ethics and tested friendships.

For me, Sunny Beach was an important lifetime experience. Despite feeling exploited and sleeping in a moldy basement of a five-star hotel while working in the resort, I earned money to pay my college entrance exams, befriend new people, became agile and appreciated challenges for my personal growth.