Academically, global cities have usually been approached in terms of their economic competitiveness as nodes within the network of globalized capital. Saskia Sassen (1991) coined the term ‘global city’ to refer to key command centers of financial transactions and accumulation. Today however, the quest for global city status also increasingly relies on the production and consumption of high-end art and culture. Kong et al. (2015) coin the term ‘global cultural cities’ and indicate that cities hoping to become global cities are recognizing that they “cannot rely on economics alone, but must also become cultural cities”.

Global cultural cities: where art and finance meet

This recognition is based on the potential of the arts to catalyze economic development. By attracting tourism, high-skilled workers and inward investment in general, the arts can play a decisive role in upgrading the financial, and innovative, prowess of cities. On the other hand, the arts also directly depend on the financial prowess of cities. After all, without a sound economic base, high-end types of art cannot flourish. These financial sources range from national and local governments to private and highly specialized financial and banking services. Along with the intrinsic reasons for the colocation of both industries in large cities (direct access to high-skilled labour, well-developed infrastructure for transport and communication, a typical openness to creativity and newcomers, etc.), it can therefore be expected that the geography of global financial centers highly intersects with that of global arts centers.

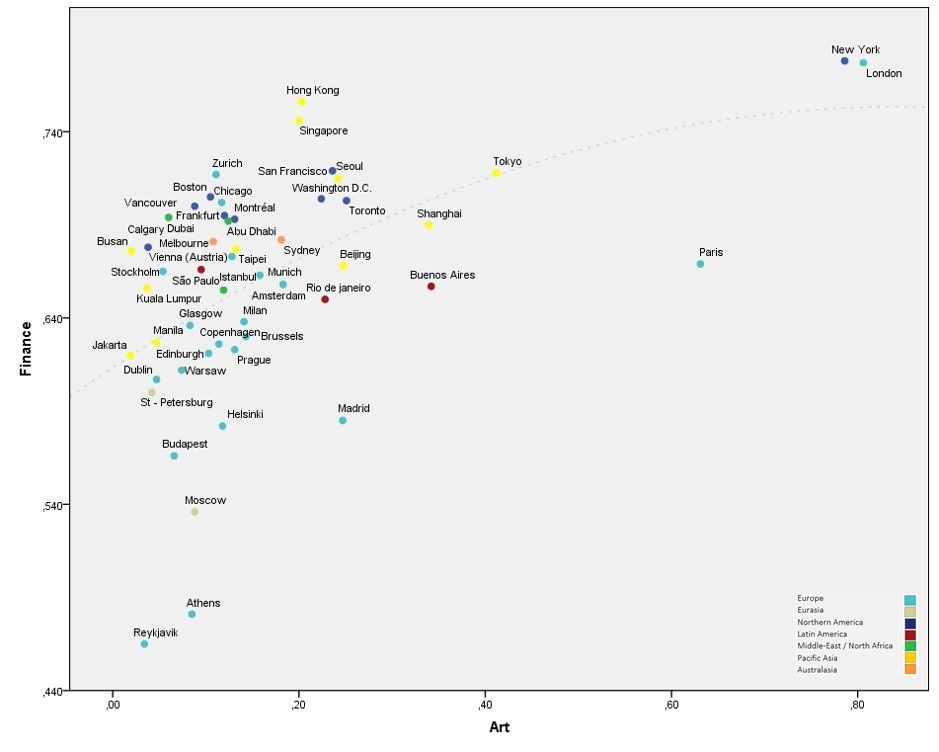

This assumption has been frequently cited, yet actual empirical analyses remain scarce. The few studies that do investigate this matter only focus on top-tier cities (e.g. Coslor and Ren, 2009), use little indicators (e.g. Kloosterman and Skorska, 2012) or focus on single cases (e.g. Chang, 2000). The overall geography of global cultural cities has thus been left fairly unexamined, until recently, as this hiatus in the global city discourse constituted the very core of my thesis research. By analyzing the correlations between a ranking of financial centers (the GFCI by the Z/Y en Group) and global art centers (a personally established ranking based on multiple indicators), the relationship between being a global financial and art center has been statistically confirmed.

The geography of global cultural cities: shift to the East?

51 cities are featuring in both rankings. These are the true global cultural cities which appear to be mainly concentrated in the current ‘arenas of globalization’, notably Europe, Northern America and Pacific Asia (Taylor et al., 2011). Figure 1 gives an overview of these cities by their performance on both rankings and by world region. Europe is clearly leading the way, with almost half of all global cultural cities on its grounds and with London (together with New York) clearly standing out. This dominant European representation should not surprise, given the continent’s rich and long cultural and economic history. Despite the short pace of time in which most Asian countries have developed economically, Pacific Asia performs second best, hosting 11 global cultural cities. It is remarkable to see cities in the East (i.e. Hong Kong, Shanghai, Beijing, Singapore, Tokyo and Seoul) soaring on both axes. This observation seems to be in line with the often cited geographical shift in the world economy from the ‘West’ to the ‘East’ (Derudder et al., 2010). While the Middle-East increasingly constitutes a part of this geographical shift and thus hosts a significant amount of global financial centers, the region lacks established global art hubs. The situation is reversed in Latin-America, Eurasia and Australasia, with more art than financial nodes. Two world regions, Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, are entirely lacking global cultural cities. Some broad historical explanations for these findings imply the late entrance of these economies in the contemporary world economy, institutional weaknesses and narrow nationalism to name a few. Hence, high-end globalized arts and finance scenes have difficulties taking off in these regions.

Global cultural cities by performance on both rankings and by world region (made by author)

Going global: cultural economic policy as a ‘quick fix’?

The one aspect most world regions have in common, is their recent and increasing interest in the pervasive role that the high-end arts can fulfill in upgrading the economy (e.g. by building flagship cultural infrastructure and hosting high-profile art exhibitions and auctions). On the one hand, this evolution is an expression of the overall transformation of advanced industrial nations into knowledge-based and service-oriented economies in which human capital has become the most valuable asset. These knowledge workers show a high affinity for the quality of place of neighborhoods and the cultural amenities they provide (Currid and Connolly, 2008). On the other hand, these cultural economic strategies are a result of the social changes in developing societies such as more leisure time, higher general welfare and hence growing expenditure on culture, entertainment and tourism, and open, cosmopolitan societies. According to Kong et al, especially cities in recently globalized, developing or post-colonial regions, such as the Middle-East and Pacific Asia, are proclaiming global city status by implementing these cultural economic policies. The inherent risk that is connected with such strategies is the prioritizing of the functional value of art over its social, esthetic and philosophical values. After all, investments in new mega art infrastructure or high-profile art events are frequently “driven by economic agendas alone, often in the search for a highly elusive ‘quick fix’” (United Nations, 2013).

Architect Jean Nouvel and HE Sheikh Sultan under the Louvre Abu Dhabi architectural model (Source: http://artasiapacific.com/Blog/LouvreAbuDhabiPresentsBirthOfAMuseum)

Abu Dhabi is a good case in point. The emirate is very busy reimagining its capital city as a global arts hub by constructing its very own cultural district, with flagship buildings from the hand of world-renowned architects. The Saadiyat cultural district will feature a Guggenheim, a Louvre (see Figure 2), a Performing Arts Center, and some 19 biennial pavilions. Ponzini (2011) speaks of a “democratic vacuum” when referring to the lack of bottom-up and cohesive cultural initiatives within the city. After all, “how well cities attract investors, foreign talents and tourists, and how ably they retain residents and aid in civic enrichment” depends on more than hardware developments. Harmonizing the ‘going-global’ and the ‘staying-local’ proves to be a delicate challenge for all cities in an era of globalization. As Chang (2000) indicates: “It is this challenge which decides which cities truly achieve Renaissance, and which merely attempt to do so, generating lots of sound and fury in the process but ultimately signifying nothing”.

Source of the image on top of this article: http://ideasgn.com/architecture/new-museum-sanaa/