This is the first part of a two-part series by Fernando Salcedo on the unique urban landscapes in South Sudan, the world’s youngest country. Part one is an investigation of the temporary waystations for South Sudanese returnees.

Imagine that you’re moving to a new neighbourhood. And, for the sake of argument, imagine that you actually interact with your neighbours: you actually talk with them, work alongside them, share facilities and services with them. Now imagine, how does your arrival effect those in your neighbourhood? Do you simply follow the ways of your neighbours? Maybe you try to change your habits as you see fit? Ultimately, the question is: does your entrance alter the social structures in the place that you are arriving to?

This is the question that led me to move to South Sudan. Since the peace agreements between the North and the South in 2005 and the South’s subsequent independence in 2011, South Sudan has experienced an influx of returnees, aiming to assist in the construction of a brand new country.

Not all returnees arrive with a similar human capital or socio-economic status of their peers, and that is why this story is lengthy and complex. For the moment, I will centre my attention to returnees that arrive form the North. Since independence, hordes of returnees have arrived to Upper Nile State in northern South Sudan, escaping violence and prosecution from the Sudanese government. An estimated 116.000 have returned to South Sudan by different means: the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) alone repatriated around 50.000 over the past year using barges, planes, and buses.

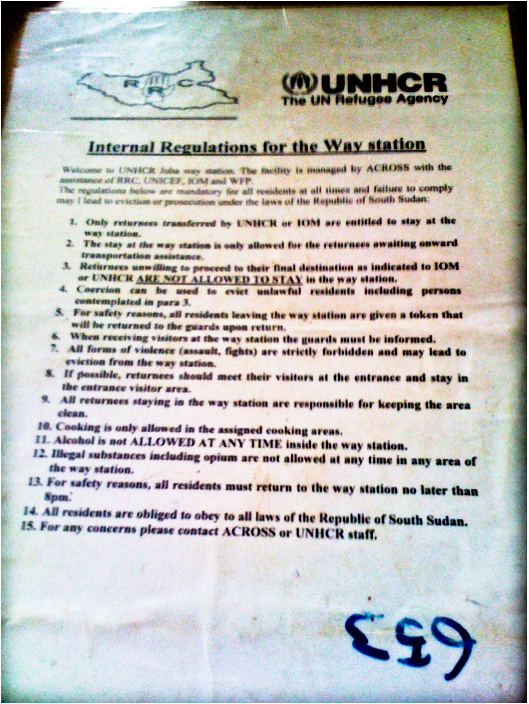

When the returnees arrive in Juba, they are placed in temporary waystations while they wait for transportation to their final destination. At this point, they are halfway along a journey that started in Renk, near border area with Sudan. After long waits under inclement weather, hunger, and tropical diseases, a little over 2.700 people, including youth and elderly, embark on a three-week journey to Juba. Returnees arrive in late August, and spend inordinate amounts of time unloading their belongings: construction materials, home appliances, beds, clothing, personal belongings.

Upon my arrival at the waystation, I noticed an array of bed frames and household appliances sat in the way of the long houses where most returnees live. Bulks and bulks of materials accumulate amidst the arid terrain. Children take the opportunity to create adventures among the barricades of furniture: it is possible to see them running around, chasing one another within the improvised luggage labyrinths.

The compound has about ten covered shelters that accommodate 200 people each. The shelters are gender-segregated, and most of them are occupied by children and women, whom altogether make up two-thirds of the current population of the way area. Those that don’t fit inside the shelters are forced to sleep outside, an incredible misfortunte considering the rainy season during August to October. During the day, the shelters are mostly empty, as children play in the sun and adults try to ensure that their belongings are property securely loaded inside the IOM trucks.

I approached the rear west side of the compound, which is surrounded by houses and only protected by a barbed-wire fence. A large group of young men and women play volleyball, while little children play their games under the supervision of a few adults. One of them approaches me to say that they are working on leisure time activities for the youth. There are few resources, and they work with the little materials available. I was wondering if this time couldn’t be better spent providing language or arithmetic courses. However, wait times at the waystation are indeterminate: creating an educational programme for people who are coming and going is just not feasible.

“The little ones,” she said while I was still metanly struggling over sexual awareness, “they are in the other side, in a tent learning English, the ABCs, and the numbers.” I replied that this is great to hear: “Can I go and see?” They nodded and guided me through.

The chants of children are clearly noticeable a few metres from the tent. “Kawhaya, kawhaya” they chant as I approach. I entered the small tent that can probably comfortably fit forty: children chanted on a continuous loop “good morning teacher, how are you? How are you?” Their voices raise as they saw me in. I greet the professor and greet the class. They chanted in response: “Good morning teacher, how are you? How are you?” I reply trying to follow their rhythm, to laughter: “I’m very well, thank you.” I say hello once again, and they yelled a warm salutation.

“The children are almost ready to finish their daily lesson, and another group will come up shortly,” the teacher said. I asked what else the children are taught. “The basics: the numbers, the alphabet, greetings, things like that.” This tiny tent is shared for almost all educational and recreational purposes in the waystation. Later on, the teacher informs me that they have several groups of children, delivering lessons to between fifteen and twenty children at once.

After a few minutes outside, one child approached me and invited me to see the rehearsal of a traditional dance. It is difficult to find leisure activities in the waystation, and, with children and young adults comprising a major portion of the current population, there is a need to promote activities targeting them. We enter the same tent where little kids sang their loopy teacher song. Two rows of adolescents aligned one before the other, enthusiastic to began the rehearsal.

They stared jumping forward and backwards at the rhythm of their palms. Left, right, left, right: trying to maintain rhythm while little children clap on the side. Quickly, a circle forms: girls move their hips and the boys try (unsuccessfully) to emulate the rhythm of their female counterparts. “Boys cannot move their hips,” one of the teachers said with laughter and I nod with a smile. I’m able to recognize the word Juba from the song, and the teacher mentions that the song refers to their arrival to the new capital city. They form a sort of conga line and with every three steps forward there is one step back. Boys continue to lose the rhythm, girls mock their unsuccessful attempt. The pace increases, the boys lose control, and most of them break the line, laughing hysterically. They all applauded to each other, and put themselves in position to try again.

After the rehearsal is finished, I chat with some other officials in the waystation, and find that it’s time for me to leave. I cannot stop thinking about the flexibility of such a temporary urban space: the waystation houses individuals and families in transit from one destination to the next, with various problems (e.g., an astronomical proportion of the waystation population being youth) having ad hoc solutions (e.g., temporary playspaces, multipurpose community centres) appearing as necessary.

There is a fluidity to this urbanscape: some, such as the current group of returnees, will depart to their final destination soon, while others will be welcomed soon enough in a different way. Future groups will organise the bedframes and housing appliances into different shapes that will define different playscapes. Chances are that other kids will learn loopy little songs in English, while the adolescents will pass the time between playing volleyball and rehearsing traditional dances.