Author Ann Thorpe made a digital visit to The Proto City’s temporary Hong Kong bureau to talk shop about design, activism, the built environment, and where we go from here as academics and designers. Her new book, Architecture & Design versus Consumerism: How Design Activism Confronts Growth, was released this summer.

The Proto City: Let’s talk about the word ‘design’. What is your conception of design at its broadest? What are its goals, strategies, and social roles?

Ann Thorpe: We all know that as a concept, “design” is a very broad umbrella. I think it is John Heskett, in Toothpicks & Logos, who says that all the concepts of design stem from the practice and activity of creating forms.

I would elaborate on this basic idea of design as creating forms and describe designers as problem solvers who balance a wide range of needs and constraints to achieve the most elegant or harmonious solution. But I should clarify that, in my book, design is anchored primarily to physical, material, and visual aspects of the built and manufactured environment. This gives a useful focus. What has always interested me about design is how it responds to, one might even say respects or challenges, its context. I think that this is the area where we are seeing the most interesting work – rethinking and challenging the norms of the consumerist context.

In design we have disciplines such as architecture, landscape architecture, fashion, new media and so forth—recognizable by their separate university degrees, professional organizations, and in some cases, licenses. I’ve learned that although everyone talks about the importance of interdisciplinary approaches — even if it is just across design disciplines — it is still hard to draw people out of their specialties. And it’s no wonder when academic and professional systems are all set up to reward and protect specialty.

I feel strongly that as we transform a consumerist society, we’ll have to look at our spatial and material design practices more holistically and engage even more outside the design disciplines. An example comes from the activist tactics I present in the book. These tactics relate far more to methods that cross design disciplines than they do to specialties.

For instance, one tactic is to use artifacts to demonstrate alternatives, another is to create exhibitions, a third is to make information visual or tactile, a fourth is develop rating or labeling systems for designed objects. All design disciplines use these tactics. My argument is that thinking of these as tactics, designers begin to focus on change solutions, and not just design solutions. Instead of thinking about design activism as the process of solving a specific design problem, awareness of different methods and tactics enables designers to evaluate a wider range of ways to try to bring about change.

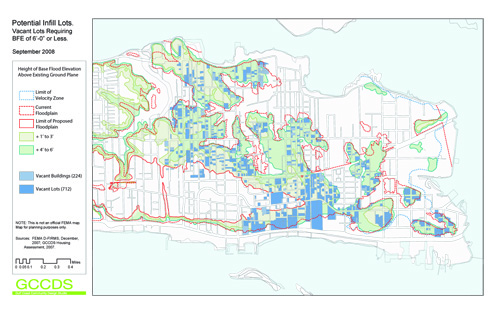

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, architects visualised critical data for East Biloxi (Image: Gulf Coast Community Design Studio)

TPC: The critique of modern consumption patterns isn’t completely new, of course: major international gatherings (e.g., summits of the WTO, IMF, G7) have given voice to the critics of contemporary capitalism, but only for a brief amount of time and in a way that seems to fall upon deaf ears. Do you see design activism as you’ve defined it as a way of publicising social critique? Or is effective design activism more subtle?

AT: You’re right that the critique is not at all new — just think about the Limits to Growth report back in the 1970s. What is new to my mind is the fact that we have serious economists arguing the feasibility of a no-growth economy, and people are starting to listen.

As for design activism, the aspiration is not simply to publicise the problem, but also to call for and influence specific change.

In order to do this, it’s important that we understand just how engrained design has been in the engines of economic growth. So in the book, I outline how design is shaped by consumerism, and how consumerism shapes design. From this understanding, we can start to explore what changes to call for, and how to use design influence to bring about change. I’m highlighting where design activism has power. And I should immediately add that rarely is design’s power alone sufficient. There’s a reason why you usually need a movement to bring about change. It takes more than any one player can offer.

We’ve seen some examples over time of design initiatives bringing about change. One example is the U.S. Green Building Council’s rating system. Rating and labeling systems are a common way of trying to capture values that the market otherwise leaves out. Although that rating system is starting to be criticised, it has had an impact as many government agencies have adopted the silver rating as the de facto building standard; that rating system raised the bar on public building performance.

Lewis and Clark State Office Building, designed by BNIM Architects. A LEED platinum building that houses the Missouri Department of Natural Resources. (Photo: Scott Myers)

Another example is the San Francisco studio Rebar’s park(ing) day: a group of designers rented a parking space and created a temporary park in it. The project caught on and led to some cities adopting pavement-to-parks programmes.

It’s important to recognize that activism, when successful, cycles upwards. No sooner is one struggle for change won than the bar is raised and a new struggle begins. We might start by struggling to get biodegradable plastic used for grocery shopping bags, but then move on to the struggle to get people to bring their own reusable bags. We’re seeing this raising of the bar around green building now too, with zero carbon building becoming a new aspiration.

What ties this back to consumerism and economic growth is the fact that when we’re talking about sustainability, most of the changes we seek reflect values that the market economy squeezes out. These areas, like stopping climate change, decreasing the concentration of wealth, or preserving cultural diversity, are all seen to cost money but provide little measurable financial return. Many would argue that using financial measures is largely inappropriate in some of these areas. These areas where activism typically operates are cash poor but value rich. People working for this kind of change have very small budgets and must leverage a range of other forms of influence and power to bring about change. In the book, I investigate these other forms of influence more explicitly for design.

TPC: As bicycle-loving Amsterdammers, we’re interested in transportation and infrastructure design. For every Amsterdam and Copenhagen, there are dozens of cities that privelege car-centric transportation. How do you see design’s role in the ongoing reorientation of urban transportation networks? Do designers take a proactive role here?

AT: I think transport is hard. We can think about proactive roles for design in a couple of ways. First, it’s important to think about transport in terms of its connection to other concerns. For example, our travel patterns link to health concerns, where too much driving, typically because of low density, car-centric development, leads to too much body fat. It might be easier to get resources put to transport when we can also argue the strong health implications.

Another way to look at transport is to consider access, putting more things close by so that we don’t have to travel as much or as far. I think we’re starting to see some creative design work that addresses access through means such as mobile structures and re-appropriation of urban space.

TPC: Recent years have seen interesting trends in terms of how public spaces are designed: think of the pedestrianisation of Times Square or the conversion of atypical spaces such as Flughafen Tempelhof. Are these cases of design activism? Or might they serve as hopeful instances that the meaning gap between design’s potential to serve the common good and consumeristic impulses could narrow in the future?

AT: I think the improvements in the public realm often do reflect activism because these are areas where typical accounting sees only costs, and benefits are hard to quantify in financial terms. To understand why the public realm and public spaces are so important, we need to highlight that consumerism provides a form of social language based on private consumption. Using this language derived from the stimulation and novelty of consumer goods and spaces, we gain social status, avoid shame, even shape our identities. The challenge is to define alternative social languages that don’t rely so heavily on positional consumption. So the public realm, and the quality of its design, is important because research suggests that by strengthening the public realm, we might be able to lessen our reliance on commercial consumption as a primary way of status or social position. The task here for designers is to provide novelty and stimulation through public and community mechanisms, rather than through private consumption and private spaces.

In response, we’re seeing designers tie novelty and stimulation to slower natural cycles. One example is lighting, where design collective Civil Twilight propose reducing the brightness of streetlights in response to the moon’s brightness. Designers are also finding other ways to enrich public spaces, for example through interactive landscapes such as Enteractive and White Noise White Light where public spaces were wired to react to public and social activity. This interaction introduced play, but also temporarily personalized the place without privatizing it.

Electroland’s Enteractive: Movements on the walkway are projected onto the side of a building, enriching public space in a way that personalises but doesn’t privatise (Photos: Electroland LLC)

TPC: Tell us how young academics and designers can maintain a level head and a creative drive amidst the frustrating and depressing discourses of politics, climate change, and a world that consistently stresses how difficult it is to succeed and create in this world. What is a revolutionary to do? How do we maintain our focus on researching and designing for the common good, even when the public doesn’t want to listen?

What is a revolutionary to do? I wish I had the answer to that! (laughs)

First, I’d say that more people than ever before are listening and more important, acting. We’re in a participatory turn with everyone producing, as well as listening, and not just on social media. What’s frustrating is that despite quite a lot of action, policies and larger systems change so slowly compared to the need.

It comes down to being conscious about what you’re doing — what’s your change solution and not just your design solution. This isn’t to say that we give up on site specific solutions or on experimental approaches. Rather, we continue to look up from this work at the movements for change going on in related areas. Weaving your actions into larger movements is the way to extend the reach of your activism and make it effective on policies and larger systems.

Also a way to stay focused on the postitive is to remember that for designers, a key role is as generative activist, rather than protest activist. Conventional activism often centres on resistance, but design activism is typically generating new ideas, proposing, and disseminating new approaches. I think social movements need much more of this work. And although you don’t need to broadcast politics in your work, make an effort to understand power relations and how to identify the power you have and where best to apply it.

This interview is part of a virtual book tour for Ann Thorpe’s book, Architecture & Design versus Consumerism (Earthscan/Routledge 2012), available from Amazon.com or use the 20% discount code BRK96 at Routledge. Read other posts: 2 and 4 October — Shareable; 9 October —Polis; 16 and 18 October — Green Conduct; 23 October — Transforming Cultures (Worldwatch); 30 October — Post Growth Institute; 6 November — no tour stop so get out and VOTE; 13 November — The Dirt (American Association of Landscape Architects); 20 November —Proto City.

About the Author

Ann Thorpe (Ann at designactivism dot net) is a Seattle- and London-based collaborative design strategist known for her generously illustrated talks that audiences describe as “brain-opening,” “intriguing and insightful,” and full of “unusual angles.” She currently serves as strategist with a Seattle-based startup, a social enterprise called luum. She also authored The Designer’s Atlas of Sustainability.