Tehran, Iran’s capital and its primary city with 8.5 million people, is experiencing a particular socioeconomic phenomenon. The city similarly to other metropolitan areas in developing countries, is becoming increasingly polarised, the gap between the rich and poor is widening, whilst the middle class is shrinking. Tehran is, geographically, economically, socially and culturally divided into two parts: north and south. A street (Enghelab (revolution) Street, running from east to west through the centre of Tehran) forms the line between these parts. In the north, the most expensive parts of the city, wealthy people live; and on the contrary, the south is mostly populated by lower middle class families and poor people. Moving along Valiasr Street (a north-south street, not only the longest street in Iran, but also in the Middle East), one can perceive how gradually the urban form, residential architecture, cars, shopping habits and even men and women’s clothing styles change. This polarisation derives from Tehran’s transitional society; as a city in a developing country, Tehran is leaving its tradition for modernity. Consequently, this transition manifests itself in almost every aspect of urban space; and one of those reflections is the dichotomy of tea houses and coffee shops. This duality can be explained through what Allen J. Scott calls regimes of capital accumulation in which he states that every period of capitalism has its own distinctive urban form with its own corresponding, equally distinctive, type of social stratification. In this respect, tea houses symbolise workshop capitalism and a traditional lifestyle, whilst coffee shops signify industrial capitalism and a modern way of life.

Tea house as a masculine space

The first tea house in Tehran appeared approximately four centuries ago; it has almost always been a place to serve the bazaar and provide a space for those who work in the bazaar. Since in contemporary Tehran, the majority of the citizens live in the southern areas, spatially, tea houses are located mostly in the south (see map below), where the majority of customers belong to bazaar and working class and are mainly in their middle aged.

The spatial distribution of tea houses in Tehran (Source: Municipality Tehran, 2014)

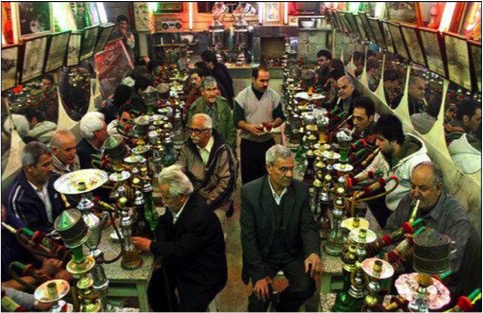

Almost every neighbourhood has its own tea house which serves as a gathering place where local people discuss about their neighbourhood, newcomers, business, society, politics. They even sometimes solve financial problems of their friends. This place has its own culture, which is traditionally related to generosity, benevolence, charity and helping people in need. In this regard, a tea house plays a role as a meeting place for perpetuating conventional and dominant values. However, as Iran has over the course of time and history always been a patriarchal society, tea houses were [and still are] a male-dominated spaces; a place with its traditional architecture, traditional music, traditional painting, traditional cuisine, traditional smoke (hookah), tea as the only beverage and men as the only customers represents a traditional society.

Coffee shop as a feminine space

In contrast, coffee shops are new urban spaces and less than two decades ago they steadily emerged in Tehran. Especially, the spatial distribution of coffee shops is important. They are predominantly situated in the Northern and wealthy districts (see map below). Coffee-shop visitors tend to be university students and affluent young women, in their 20s/30s (the first generation after Iran’s 1979 revolution), who desire to be free of the social pressures imposed by men. Coffee shop culture, accordingly, is a feminine culture in which women are trying to build their own space to be modern. Put differently, as Henri Lefebvre articulates, groups and classes cannot constitute themselves, or recognise one another, as subjects unless they generate their own space. Hereof, the female patrons who frequent coffee shop to smoke (where they are not as frowned upon as in public spaces) and socialise with friends have created a comfortable space for themselves to harmonise with other people who have the same thoughts and lifestyle.

A coffee shop in Northern Tehran (Source: Reza Shaker Ardekani)

These people ideologically and professionally symbolise a new urban generation: intellectual and well-educated. Coffee shops, with their long list of non-alcoholic, western beverages, modern interior architecture, modern (and recently fusion) music, modern painting and the presence of all genders, stands against tea houses and represent a distinction between tradition/modernity, east/west and old/new. In other words, coffee-shop goers [the young, wealthy/intellectual generation] who think and act differently from, and sometimes against, the mainstream beliefs of the society, have built a semi-public/semi-private space for themselves to practice and experience their own values, to change the society with their critical, creative ideas, whilst their counterparts, tea house goers, effort to conservatively preserve it.

The spatial distribution of coffee shops in Tehran (Source: Municipality Tehran, 2014)

Traditional tea houses and modern coffee shops in Tehran both represent third places for their regulars. Based on Bourdieusian framework of capitals, the elite/wealthy class who are living in the northern parts of the city are trying to distinct themselves morally, socioeconomically, culturally, and even geographically/spatially from the rest of the society (especially the southern working class). This dichotomy is only one example. A closer look at this classes would reveal other dualities such as music, architecture, clothing style and so on. However, it can be seen from a Hegelian dialectic. A “thesis” (e.g. tea houses) causes the creation of its “antithesis” (e.g. coffee shops), and would eventually result in a “synthesis”. Nevertheless, the question is: would Tehranians be able to build an identity somewhere between tradition and modernity spectrums, a dialogue between east and west, escape from this duality and establish a synthesis third place?