New Street, Birmingham’s central railway station, is currently experiencing its second radical redevelopment. Its first redevelopment was in the 1960s and has become infamous as one of the prime examples of modernist architecture in the city. Its current redevelopment, under the header New Street, New Start, does not remain limited to the station only; along with it, the probably even more disliked Palassades shopping centre situated on top of the station is replaced by the Grand Central shopping mall, and a new public square is created. The Ladywood House, a nine-storey office block on top of the station, is also to be redeveloped, but in June 2015 it was still for sale. The multi-story car park also situated on top of the old station has been demolished.

The new entrance to Birmingham New Street station (left), next to the last remains of shopping mall Palisades that will soon be demolished (Photo: Marco Bontje)

The new John Lewis department store, part of the new Grand Central shopping mall (Photo: Marco Bontje)

Urban design opinions and tastes differ, of course, and they can change drastically through time. In the 1960s and early 1970s the radical modernisation of Birmingham probably had widespread support at least among architects, urban designers and the city government. But in the 1980s, there were only very few people (if any) left in Birmingham that liked New Street Station and The Pallasades. Outside, the complex was mainly concrete and tiles; inside, it was mainly dark and especially in the shopping centre you could easily get lost. The rapidly growing passenger volumes made the station even more problematic; overcrowding made arrival and departure, let alone staying longer in the station than necessary, an uncomfortable experience. New Street topped the wrong lists of several polls: readers of the magazine Country Life ranked it the second worst architectural eyesore in the UK in 2003, and it had the lowest passenger satisfaction in a poll of Passenger Focus in 2007.

The New Street / Grand Central project follows in the footsteps of many urban regeneration projects in Birmingham’s city centre and adjacent areas like East Side, Aston and the Canal District since the 1980s. The modernist make-over of the city centre more in general also became discredited. Kennedy (2004, p. 1) called modernist Birmingham “a dystopian lesson in urban decline – reviled for its concrete brutalism and its disdain for the pedestrian, it became a focus for anti-urban sentiment.”

The result was that the city centre became a no-go area. In 2005, while doing fieldwork in Birmingham for the Inventive City-Regions project, one of my interview respondents said: “Twenty years ago, you would not have visitors in the city centre. This was the pit!” Birmingham’s inner city had become dominated by car infrastructure. A major obstacle was the ring road, disconnecting the centre from the rest of the city and therefore nicknamed the concrete collar. Parts of the elevated ring road were brought down to ground level or in tunnels and new underpasses were created under those road parts that remained elevated; this reconnected the city centre with the adjacent neighbourhoods and gave a dramatic boost to urban regeneration. Other strategic projects included the International Convention Centre, Symphony Hall and National Indoor Arena, the redevelopment of the Bull Ring shopping centre, and the pedestrianisation of shopping streets.

Not by coincidence, these regeneration projects include several iconic buildings. The New Street / Grand Central complex will join icons like the Selfridges department store (2003) and the New Public Library (2013), winning several design awards and promoting the new image of ‘city of design’ that Birmingham wishes to spread to the outside world. Like in several other UK cities, the redesigned city centre became a crucial element of a broader urban and regional redevelopment strategy. The demise of modernist Birmingham had gone hand in hand with the demise of Birmingham’s manufacturing-based economy. In the 1980s, Birmingham’s city leaders were among the first in the UK to recognise an attractively designed city centre as an essential element of its strategy to attract private investment and revitalise its economy (see, for example, this article by Hubbard).

With the New Street redevelopment still in full progress (I visited it in June 2015; its completion is planned in September 2015), the striking differences with the old New Street station already become apparent. It is much easier to find your way through the station than it used to be, there is much more daylight entering the building because of the new atrium roof and because concrete was largely replaced by glass and steel, and despite intensive use throughout the day the passenger concourses do not feel too crowded. While opinions on the outside appearance of the building may well differ (maybe a bit too much glass, maybe a bit too ‘iconic’?), both the professional design community and the general public so far seem mostly positive. The transformation from a sober functionalist complex where people only went through because they had to, into an eye-catching attractive place to be, may indeed work out as planned.

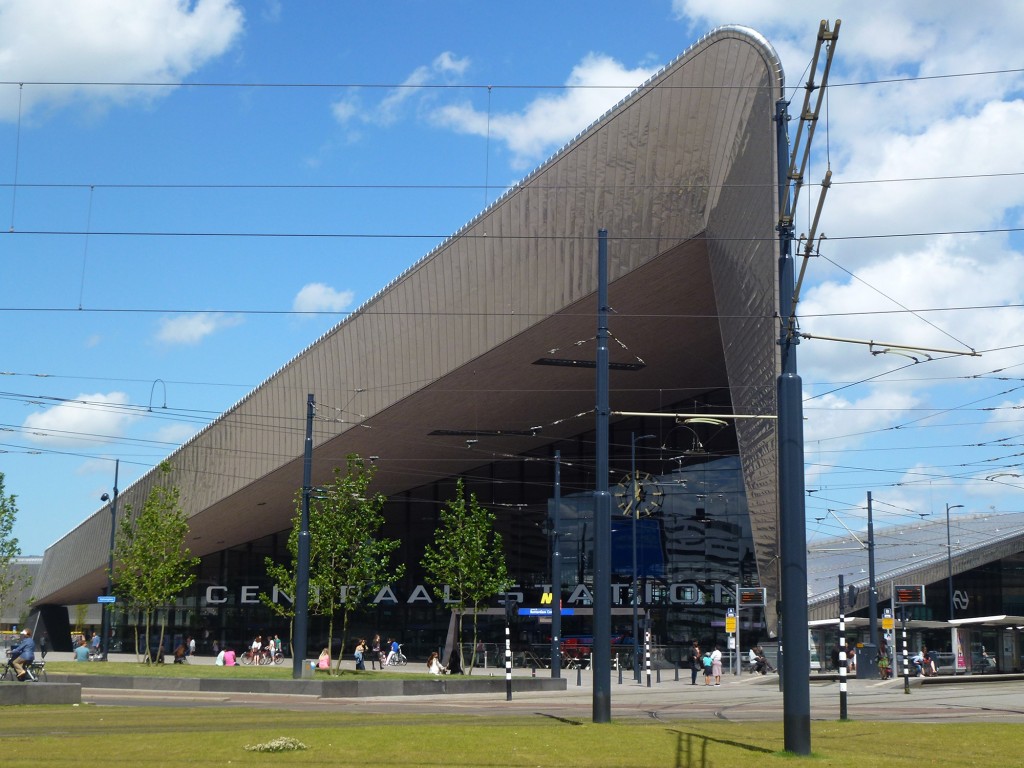

The Birmingham New Street / Grand Central redevelopment shows striking parallels with another major railway station redevelopment that has recently been completed: Rotterdam Central, the central station of Rotterdam. The city centre of Rotterdam was almost completely destroyed by German bombings and the fires following it in May 1940. Already during the war, plans to develop the city centre were developed. Rotterdam used this disaster as an opportunity to radically modernise its city centre. While Birmingham (also damaged in World War II, but much less dramatic than Rotterdam) had to demolish many Victorian buildings to make its modernisation possible, Rotterdam’s inner city modernisation started almost from scratch. The new Rotterdam Central Station, replacing two old stations, was opened in 1957. Like Birmingham New Street, it became outdated some decades later because of increased passenger volumes and new high speed rail connections. Meanwhile, its immediate urban environment had partly changed too: a second wave of modernization had started in the 1980s and the station did not fit as well in its environment anymore as it did when it was opened. As one of six New Key Projects around major railway hubs in the Netherlands, Rotterdam Central was redeveloped into a 21st-century public transport terminal.

Getting rid of modernist heritage and replacing it with early 21st century iconic starchitecture raises questions about how to redevelop cities. Was modernism just a big mistake in retrospect and should we demolish all modernist buildings and infrastructures to create more attractive inner cities? Or were there maybe also modernist buildings that could still be appreciated and find a proper use in the 21st-century city? Rotterdam seems a bit less anti-modernist than Birmingham nowadays; see for example the reminders of modernist past in and close to Rotterdam Central: the clock and Rotterdam Central sign of the old station have been saved, and the neighbouring Groothandelsgebouw is also still there. The demolition of the old Rotterdam Central Station was actually regretted by quite some Rotterdammers, opposite to the general relief in Birmingham when New Street was finally redeveloped. Birmingham still has a lot of modernism to demolish left, but maybe parts of that modernist heritage should not face that fate? A few modernist fans apparently are still left in Birmingham. They campaigned for years to keep the old Central Library, nicknamed Ziggurat, but lost the battle; the building will be demolished after all.

Groothandelsgebouw and the office project First Rotterdam under construction, next to Rotterdam Central (Photo: Marco Bontje)

Announcement of redevelopment plans of the Paradise area, including the demolition of the old Central Library (Photo: Marco Bontje)

Or are we maybe in danger of repeating the same mistakes when inner cities are filled with one iconic building after another? How will the new railway stations, shopping malls, office blocks and mixed-use complexes built since the early 1990s be appreciated in two or three decades from now? Exploring possible opportunities and threats of Birmingham’s future, one of the threats we identified in our Inventive City-Regions analysis was ‘modernising too radically once more.’ Maybe incremental small changes would work better than large-scale dramatic interventions?

We will have to wait and see how long the currently mostly positive opinion on Birmingham’s inner-city makeover will last. A possibly worrying sign for how long redeveloped areas can stand the test of time is The Mailbox, a posh mall, hotel, and gastronomy complex close to New Street station. It was opened in 2000, but only thirteen years later, in 2013, a major redevelopment of the complex was already announced.