Beyond natural disasters and poverty

Bangladesh has recently made the headlines of western media as a country of floods, collapsing garment factories and poverty. In addition, these media coverings often incorrectly portray the country as religiously and ethnically homogenous. Through this contribution I hope to enrich the image of the country and challenge some of the often implicit assumptions in western media. I will do so by looking at a largely neglected process of social change; the rapid urbanization and the challenges that arise as a result of it. This contribution is an outcome from my own experiences from a three-month fieldwork period in 2012 in the country’s capital Dhaka on urban migration and structural urban challenges in the city. During my stay my attention was drawn towards Chakma migrants, an ethnic minority from the Chittagong Hill Tracts, a rural region in the Southeast of Bangladesh. As the sections beneath will illustrate, Chakma migrants do not only face chronic urban challenges such as air pollution, traffic congestion and housing problems as other Dhaka inhabitants, but also face social exclusion on the basis of their ethnic belonging. Namely, Chakma migrants are by many other Bangladeshis considered to be underdeveloped people from the jungle. More broadly, the focus on this group of migrants reveals the additional challenges vulnerable social groups may face when migrating to major urban centers.

Dhaka’s explosive growth and migration

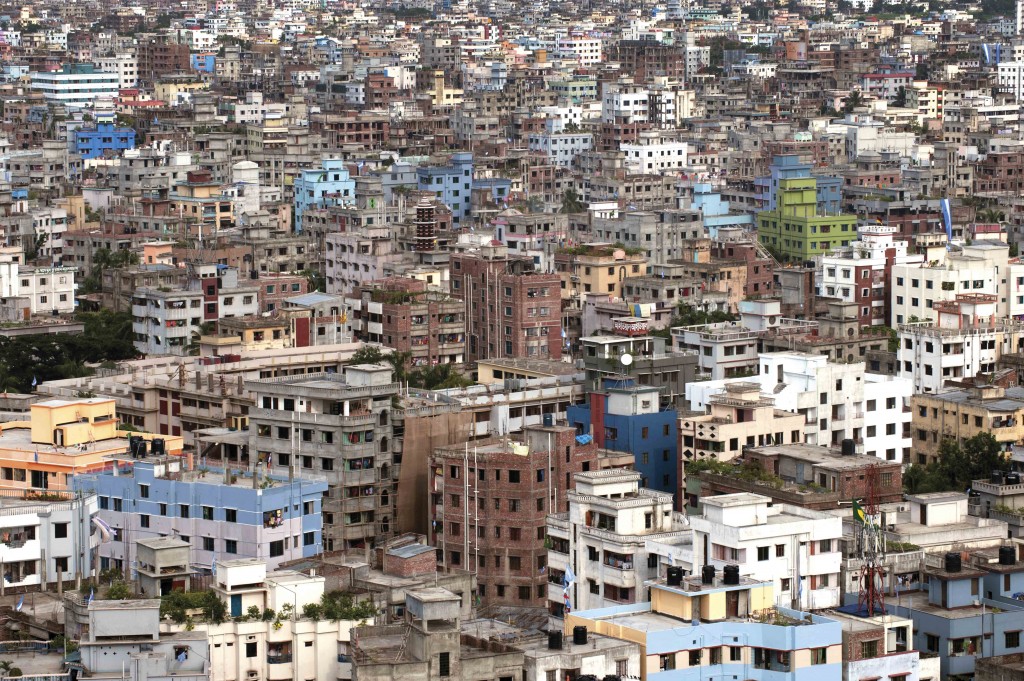

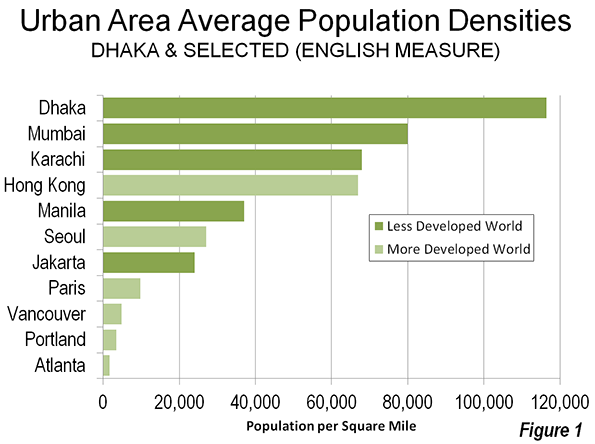

Bangladesh’s capital city Dhaka is changing rapidly due to the country’s increasing urban population. The city witnessed explosive population growth in recent decades. Whereas the city had 1,3 million inhabitants in 1970 this figure increased to over 15 million today. Since the UN estimates that the city will have over 23 million inhabitants by 2025 there is no reason to assume that this growth will stagnate anywhere soon. Taking into account that Dhaka is already the most densely populated megacity in the world with over 118,000 people per square mile (see figure 1), it will be a major challenge to make the city a pleasant place to live for its (new) inhabitants. This since the explosive growth creates several chronic urban problems for its inhabitants, particularly in electricity and water supply, extreme air pollution and an inadequate system of public transport.

Population Densities in Urban Areas (on average) . Source: newgeography.com

The majority of the city’s annual population growth, approximately 60% or 300,000 to 400,000 people are rural urban migrants coming to the city. People move to the city to benefit from the economic opportunities the city provides for example in the garment industry. Along with people from every corner of Bangladesh, the number of Chakma migrants coming to Dhaka has also strongly increased in recent decades. Whereas there were a few dozens of mainly Chakma students in the 1980s I estimate there to be around 15,000 Chakma migrants in the city at the moment. The following section will address the structural urban challenges that inhabitants in Dhaka face, after which the additional challenges for Chakma migrants are addressed.

Chronic Urban Challenges; Air Pollution and Traffic Congestion

Traffic Congestion on Mirpur Road, Dhaka. (photo taken by author, February 2012)

Estimates on air pollution by the Air Quality Management Project (AQMP) funded by the Bangladeshi government and the World Bank estimate that over 15,000 premature deaths occur annually in Dhaka because of air pollution. In addition, millions of respiratory and pulmonary illnesses occur because of polluted air. Another major problem in the city is extreme traffic congestion. The primary cause for this is the imbalance between rapid population growth and limited improvements in infrastructure. As a result the World Bank has given priority to upgrading transport services and infrastructure in the city in the upcoming decade but whether this will be enough to reduce congestion remains to be seen. Furthermore the lack of safety in traffic reduces the incentive to go out. Bangladesh has one of the highest traffic fatalities in the world and inhabitants of the city deal with experiences of (near) accidents on a daily basis, fueling feelings of insecurity in the city.

Social exclusion and additional challenges for Chakma migrants

The focus on Chakma migrants in relation to urbanization allows for an adjustment of simplified representations of Bangladesh as an Islamic-Bengali nation in which ethnic minorities are only found in peripheral areas. Bangladesh is often portrayed as an ethnic and religious homogeneous country solely inhabited by ethnic Bengalis. Although a vast majority of the countries’ inhabitants do categorize themselves as Bengali Muslims, the country is actually home to many ethnic and religious minorities. Since Bangladesh’s independence from Pakistan in 1971 the process of nation building has largely excluded these minorities since being an ethnic Bengali – and more recently being a Muslim – became the most important characteristics of being considered a Bangladeshi national. This also means that people that do not look like Bengalis or have a different religious affiliation are often not considered as ‘true’ Bangladeshis.

This is exactly the case with Chakmas migrants. Chakmas rather resemble people from Northeast India, Thailand and Myanmar making them ‘look different’ from Bengali Bangladeshis. In addition, most of them are Buddhists. These differences are constructed in such a way in Bangladesh that Chakmas are not seen as ‘true’ Bangladeshis. More problematic is that Chakmas have often been portrayed in popular media and even schoolbooks as underdeveloped, uncivilized people living in a jungle. These stereotypical representations come to the fore when Chakmas migrate to Dhaka where they find themselves in the social, cultural and economic heart of Bangladesh while being confronted with exclusion because of their Chakma background. This comes to the fore through the story that Shoran, a 26 years old student, told me about when he came to Dhaka for the first time over six years ago:

“When I first arrived at the campus my classmates asked me about my food habits. In primary school they had been taught that we eat jungle foods you know. So I explained them that it is similar to theirs. They thought we eat snakes, frogs, monkeys and such. It is because it was in their schoolbooks. They used to say we were underdeveloped, not wearing clothes and such.”

Thus Chakmas in Dhaka do not only deal with the localized structural urban challenges as all migrants do, but they also face social exclusion and public harassment on a daily basis. This is a result of the dominant stereotypical representations of them as underdeveloped people from a jungle which forms a stark contrast with their actual modern lifestyle in the urban jungle of Dhaka. Paradoxically, they find themselves challenged by moving from a rural area that is imagined by many Bangladeshis as an untouched jungle to Dhaka’s urban jungle.