Access to transportation is fundamental for an economically and socially sustainable life. Nevertheless, many African countries lack an integrative and well planned public transportation system. In Kenya the combination of many local and regional bottom up transit companies have created a layered transportation system that can get you almost everywhere. While travelling in Kenya, I wanted to learn more about this spontaneous system of public transit modes.

There is a huge mobility demand as people need to have access to jobs, markets and education. As a result, starting a transportation company is an investment with limited risks which provides a relative stable source of income for chauffeurs and drivers assistants. There is a dark side to the system though. The bottom up emerged system has limited oversight and control, resulting in a high rate of traffic accidents, overcrowding minibuses and unsafe use of motorcycles.

A large pimped ‘Matatu’ as an cooperative investment ready to roll (picture by author)

Transport as Investment

The lack of official public transport created economic opportunities for all owners of some form of transport. This doesn’t mean all public transport modes are informal. The main transport mode is the ‘Matatu’, minibuses that are often operated as a Savings and Credit Cooperative Organization (SACCO’s). Sacco’s are an investment tools whereby members invest together in buying a for example a minivan and share profits. SACCO is a government program to enable local investment in companies resulting in jobs. The Matatus have to carry a government license and insurance sticker which has to be renewed yearly. Furthermore, the matatu sector has to follow rules like the maximum number of passengers, speed limits and driver’s licences. Thus, it is in practice a semi controlled and government stimulated form of transportation. Furthermore, the matatu as a shared good also benefits more people looking for a chauffeur job. The main driver shares the minivan with other drivers, all taking multiple short shifts of a couple of hours to half a day, thus sharing the economic opportunity with a wider community.

Although matatu’s are the most formalized transport companies, less formal modes like motorcycles, bicycles and TukTuks are also all used as investments and as main sources of income for drivers and owners and investors. A motorcycle, or ‘Boda Boda’ can be shared in three or more shifts, for instance a morning, afternoon and evening shift, all by different drivers who will pay a fixed fee to the motorcycle owner. What is profited above the fixed fee can be taken home as income. Bicycles (or ‘Picky Pickys’) are also transportation modes but are decreasing in use as the crowded urban streets decrease safe riding space. This is problematic as the bicycle is one of the most affordable transport modes but this mode is also most under pressure in urban areas, thereby excluding the lowest income classes towards safe travel option (see also the article on social inclusion and cycling in Kisumu, Kenya by Alando and Scheiner from 2016).

Boda Bodas with passengers (picture by author)

Transport as Epidemic

Many Kenyans earn a living through their transport endeavours, and in absence of a top-down, government planned public transportation network, the Kenyan society benefits greatly as people would be nowhere without it. However, it is not just an economic succes story. Traffic accidents account for the third biggest cause of death in Kenya after Malaria and HIV/AIDS (Chitere, Kibua, & Kenyatta, 1992). The staggering amount of deaths makes the bottom-up transport system an epidemic that puts the same people at risk who need these transport modes to sustain in their daily livelihood.

From personal observations, it is indeed not without risk to travel using motorcycles and matatus. Your safest bet is the Tuk Tuk, but that won’t get you very far and it’s highly uncomfortable. For regional transport the Matatus are the most affordable and frequent option. Although the police are checking the vans on overcrowding at road check points, it still occurs frequently that matatu’s are stuffed with passengers sharing a four seat bench with six, a bucket of fresh fish and the occasional chicken. As there are abundant Matatus in disrepair, this overcrowding can result in the driver losing control of the vehicle (For example this crash reported in the national newspaper Daily Nation). It must be noted that I have had good experiences as well were the driver would not exceed the maximum highway speed of 80 kph and let people standing by the side of the road when all seats are taken. But this is a rare occasion as most minivans are owned by a SACCO for investment purposes which incentivizes maximum cash flows for all who have invested in the minivan, and the driver needs to pay a fixed fee to the SACCO before he starts earning.

De Bado Bado’s are something else. While these 150cc motorcycles look treacherous they are actually comfortable. They are used as a mode to get you to more remote areas or places where the matatus won’t go. These are often dirt roads, and as long as they are dry and it is not too hilly, a safe ride can be expected. In Kisumu I have taken a ride through the busy city and it is in this situation that you have to worry because you can get slammed between matatu’s and trucks in a chaos. Hence, within cities you are better off with taking the Tuk Tuk (hands on board please).

Taking a designated Tuk Tuk after a drink in the city of Kisumu (picture by author)

Alternative Modes of Transportation

The abundance of transport has led to standard fares for specific times and distances. Thus despite the large amount of transportation services, standardization on fares and routes has occurred in practice. However, when you’re a visitor (also called ‘muzungu’) different rates apply or you have to negotiate. In Kisumu, the third biggest city in Kenia, this led to the unusual moment where the Boda Boda driver did not know the muzungu price as Kisumu is not commonly visited by travellers. This is different in the more touristy coastal area where as a tourist you always pay a premium and if you negotiate too harshly you’re left stranded as there is always some other tourist to take in. In Nairobi this problem is easily circumvented as Uber has grown big in just a couple of years. As you pay by card automatically there is no negotiating, while simultaneously the driver has an incentive to drive in accordance with traffic rules because bad reviews are bad for business.

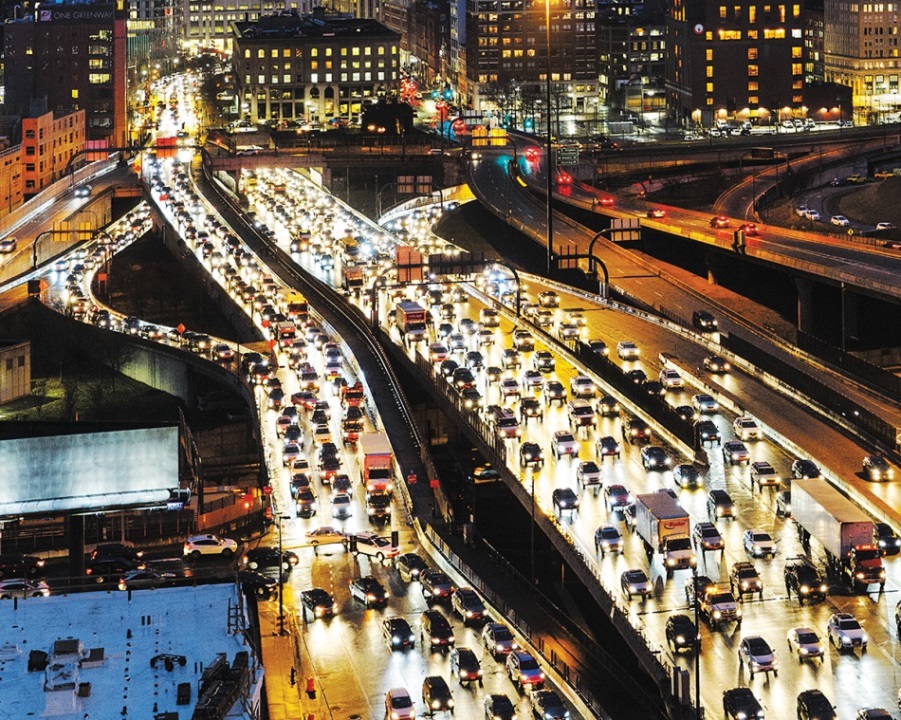

There are some more ‘institutionalised’ modes of transportation which are costly and therefore exclude most of the Kenyan population. First, there is one train service between Nairobi and Mombasa. It is a beautiful fifteen hour ride or twenty-two hours if you include the seven hours of delay. The train used to be upper-class and is still marketed as being high-end, but the only classy about the train is the availability of cold beers, which you need because it is hot and there is no operating cooling system. Kenya, or actually China, is investing heavily in its rail system though, so the old train might be gone soon. Secondly there are larger national operating bus companies. These buses are more organized than the Matatus as they have booking offices in most of the bigger cities and even label your bags. Lastly, private vehicle ownership is on the rise, but mostly in the Nairobi region which is also known for its hours and hours of traffic jams, even up to three days as reported by InHabitad.

View from the train (picture by author)

Kenya has no publically controlled and planned transport system but a comprehensive and layered system of bottom-up mobility services. These layers of different transit modes provide people with income, access to jobs and education, but also cause of a high number of traffic accidents and deaths in the country. With the private cars not being a solution due to traffic jams, Kenya’s best strategy is to enhance the quality of the semi-informal, locally organized transit companies while professionalizing long distance and urban routes by train and bus.