In times when an increasing amount of the population in many Western countries is becoming obese, urban scholars came up with theories about so-called ‘food deserts’. To what extent does this phenomenon indeed exist, and where exactly are we able to actually find them?

A review on the literature about food deserts so far makes clear that it is fundamentally controversial. First and foremost, this is because the concept itself still requires a clear definition. Nowadays, most people agree that a food desert can be understood as an often deprived part of a city where residents have limited or no access to an affordable and healthy diet and are thus forced to unilateral or simply unhealthy food (see: Cummins & Macintyre, 2002).

What remains still is the question of what should be considered to be a healthy food supply. Most scholars on the subject used supermarkets as a proxy for access to healthy food, since people will at least have the opportunity to choose healthy food when a supermarket is nearby. For this reason, several cities, such as Pittsburgh, try to improve supermarket access for those with poor access. A lot closer to home, even the neighbourhood in Glasgow where I am currently living in myself seemed to be in desperate need of affordable healthy food supply at the beginning of this millennium. Hence, a Lidl has been established in the centre of the area which fits very well in the city council’s aims to renovate the once so infamous and still deprived area.

The second topic of debate within the existing literature on food deserts is whether they do in fact exist outside of the United States or not. According to Beaulac et al (2007), evidence of the existence of food deserts in other high-income countries, such as the United Kingdom, is sparse and equivocal. Cummins & McIntyre even declared in 2002 that the existence of British food deserts could be seen as a so-called ‘factoid’: an assumption that is repeated many times until it is generally considered to be the truth.

Stephan Valenta and I decided earlier this year to consider Amsterdam in this regard with GIS tools. In Amsterdam, many policy makers and health institutions recently expressed concern regarding the increasing obesity levels amongst schoolchildren. According to Het Parool, in some schools in Amsterdam’s Nieuw-West district, about 40% of the children are overweight. The problems of obesity are largely located at the outskirts of the city: besides Nieuw-West, Amsterdam Noord and -Zuidoost seem to be particularly vulnerable areas. The Municipal Health Service of Amsterdam (GGD) published a report in 2005 (PDF), stating that the highest risk factors for children with overweight are an irregular and unilateral food pattern and a lack of physical exercise. One of the members of the Amsterdam city council also recently proposed measures prohibiting the sale of unhealthy foods such as chips, kebab, and energy drinks in the vicinity of schools, in order to combat student obesity.

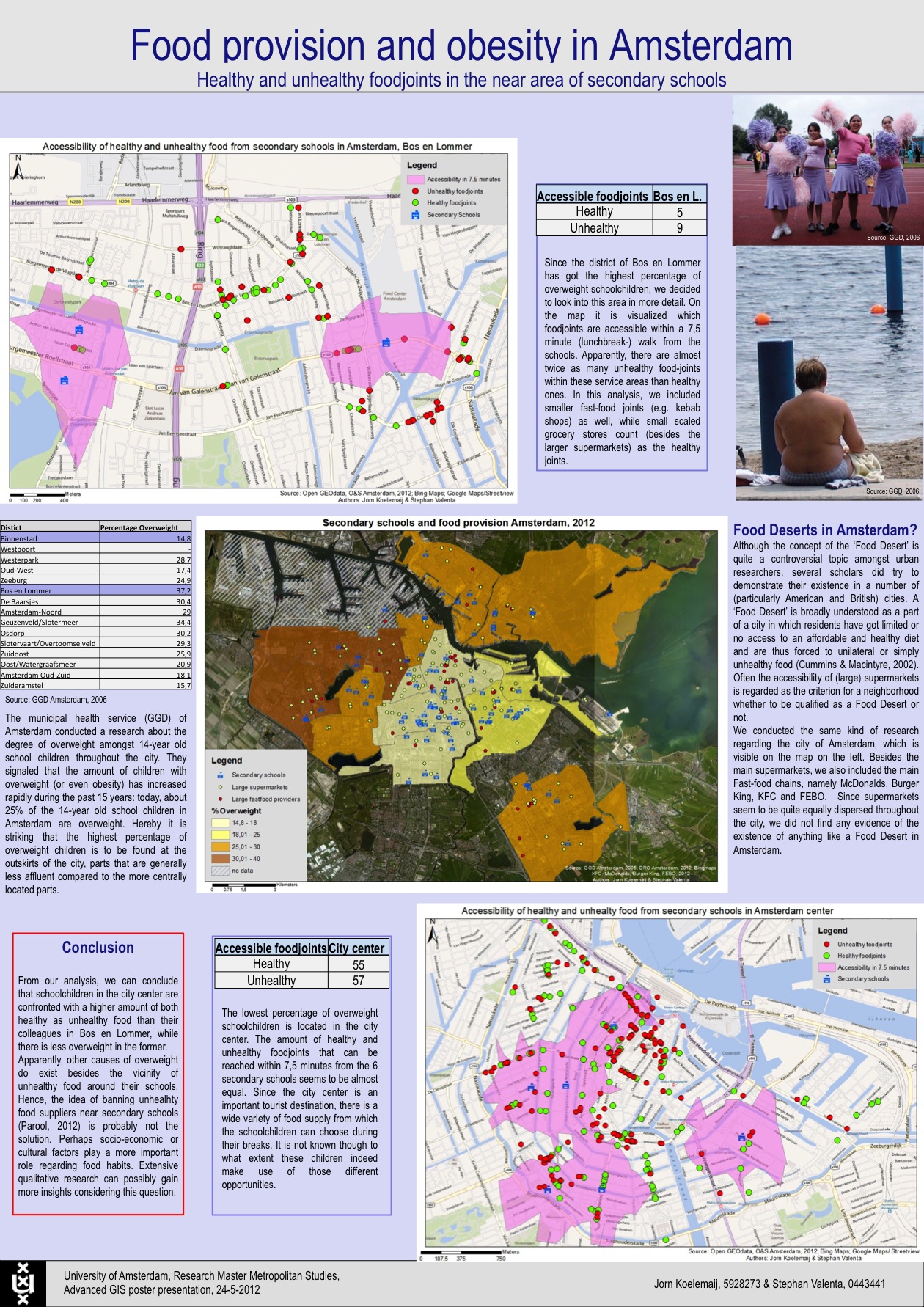

Research poster by Jorn Koelemaij and Stephan Valenta performing a GIS analysis on whether or not food deserts exist in Amsterdam neighbourhoods

Click image to view the full poster

Our research mainly focused on the two districts in Amsterdam with respectively the highest and lowest percentage of overweight schoolchildren. Using a network analysis in ArcGIS, we calculated the service area taken from the secondary schools in those two districts, looking at the amount of both healthy and unhealthy food chains that were reasonably reachable during their lunch breaks. A summary of our findings can be found on this poster.

According to our observations, we made two conclusions. First and foremost, food deserts seems to be non-existent in Amsterdam, and, second, that other causes of obesity do probably exist besides the proximity of unhealthy foods. Perhaps socio-economic or cultural factors play a more important role regarding food habits. This is moreover in line with Hillary J. Shaw’s line of thinking, who proposed that the concept of ‘access’ could be broken down into three contributory factors to access problems: ability, assets, and attitude. In other words, physical, financial and mental factors can play an important role causing one’s unhealthy food habits as well.

Does all of this thus mean that food deserts in cities are actually complete fairy tales outside of the United States? I think that this still depends on the exact meaning that you might want to attach to the concept. To return to my own lovely Glaswegian neighbourhood of Possil Park: right opposite to my flat, one will find the giant Asian foodstore called Seawoo, which indeed sells fruits and vegetables as well, but where the majority of the customers are part of the Asian population that specifically comes here from throughout all parts of the city in order to buy Asian foodstuffs. In the rare case that I do not fancy rice or noodles, I need to walk quite a distance, either to the Lidl or to a supermarket in a different area. For me personally this is not much of a problem, but for elderly residents or those with mobility issues, it could be. Why endeavour to combat those constraints if they could also just order some fast food?

Furthermore, every morning when I’m walking to university, the almost irresistible smell of fries, hamburgers, and sausages is coming towards me. Directly next to the Woodside Health Centre, one will find a typical British snackbar. The doctors inside the health centres will probably regard this with sorrow. A cactus in the desert or just an odd tree in a fertile valley? Probably some extensive, qualitative research is needed to get a clearer picture about food accessibility and choices of people.