Urban informality is hardly a new reality for the world’s cities. The term itself has a young theoretical life, being championed by urbanist Ananya Roy as a lens with which to think about how cities are planned and made without the need to approach an urban planning department. Informal settlements exist in a huge variety of forms, from the gradual occupation of the Torre David skyscraper in Caracas to the built-overnight towers of outer Istanbul, and offer ad hoc solutions for housing, retail, and community space alongside questionable building quality.

Architectural details in the urban village often have multiple functions that would otherwise be discouraged elsewhere in the formal city (Photo: psychosteria on Flickr)

The Chinese manifestation of urban informality is the urban village. As Stefan Al, architect and Associate Professor of Urban Design at the University of Pennsylvania, sees it, China’s urban villages bear few, if any, similarities to the favelas of Brazil. “They’re actually fully intertwined, although they look like the polar opposite,” notes Al. “From an economic perspective, the urban villages and the city are completely related. The only reason urban villages exist is the inability of the Chinese government to provide adequate housing for millions of people.”

Urban village dwellings tend to be self-built in close proximity to one another (Photo: dcmaster on Flickr)

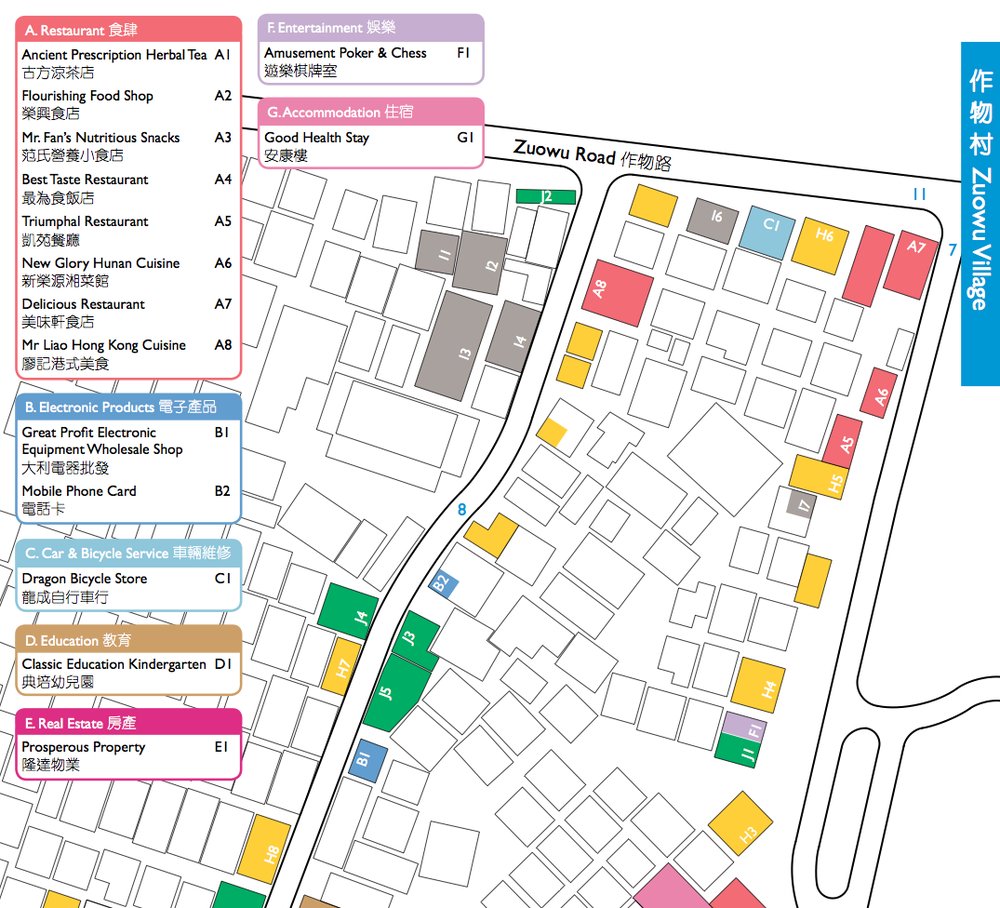

Oftentimes, an urban village is specialised in a specific industry, sometimes to the extent that they dictate the sector at a national level, such as Shipai Village in Guangzhou, which sets the price levels for many electronic components, or Dafen Village in Shenzhen, which is a leader in copied versions of paintings as well as being an incubator for fresh artistic talent.

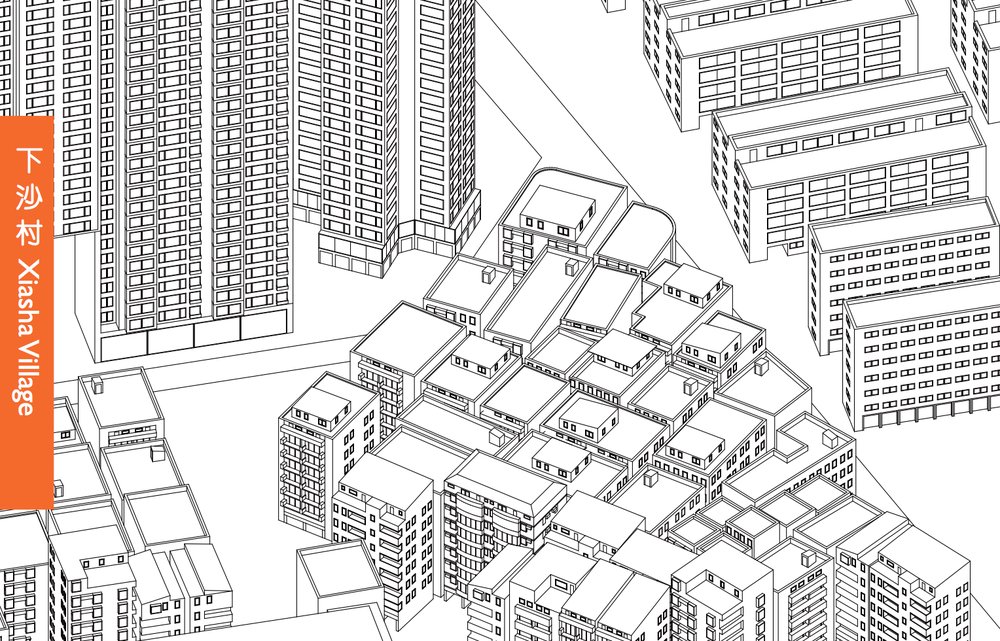

Axonometric view of building typologies in Xiasha Village (Image: Villages in the City, edited by Stefan Al)

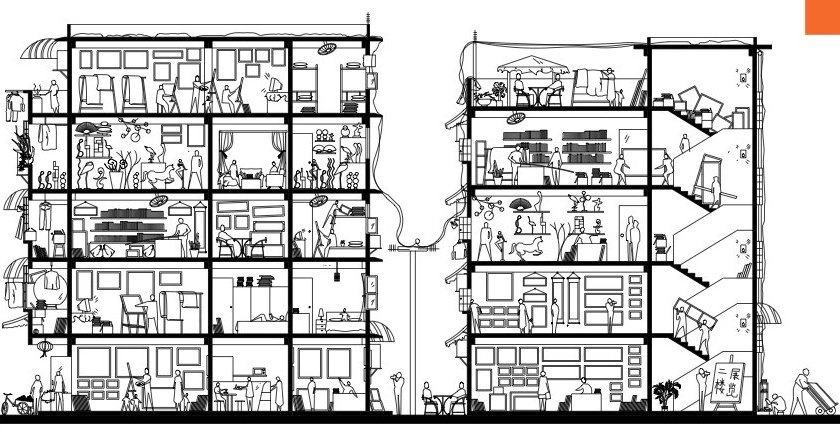

If the urban village is not a shanty town, then what does it look like? Al’s edited volume, Villages in the City: A Guide to South China’s Informal Settlements, examines the design elements, building uses, and housing typologies typical to a southern Chinese urban village through a LOMO-filtered lens: Al suggests that “by portraying them through this LOMO filter, we could show and celebrate the unpredictability and spontaneity of this part of the city.” They are specific design-wise to the villages themselves, with narrow alleyways and no building setbacks (leading to what residents refer to as a ‘thin line sky’ being the only daylight you can see in certain streets) like the cities that surround them. But they are also examples of high-quality urban design, with inclusive and open public spaces that allow for ad hoc use and build a cohesive community.

Despite their narrow streets, urban villages are often teeming with life (Photo: Yumian Deng)

The radically different design principles found in urban villages as opposed to the city itself begs the question of how these villages became part of their cities in the first place. Their existence stems out of a system of thousands of village collectives across the country that eventually became too close to ever-expanding cities that were rapidly buying up all of the surrounding land. According to Al, “it’s land that’s owned by the village collective. They have their own garbage disposal, their own police force, and they’re not subject to city zoning laws.” This opposition can be present in the actual built environment itself. On the outskirts of a city, an urban village may not have buildings that exceed eight stories tall, but within more central areas of the city, some villages are constructing skyscrapers of their own and maintaining population density levels that would not be possible in the city proper.

Catalogue of businesses in Zuowu Village in Zhuhai (Image: Villages in the City, edited by Stefan Al)

Despite the ingenuity bred out of an informal situation, urban villages remain under threat. In the process of cataloguing these informal neighbourhoods, Al and his research team became aware of the future of these areas, warning that “what they call redevelopment is really demolition. If you look at Guangzhou, they send out a bunch of planners to go to all of these different villages and what typically happens is they identify a few ancient temples and trees to be preserved and everything else gets wiped out with a completely new city.” Cities the world over have gone through similar narratives, but none on the same scale as in China, where ‘redevelopment’ is a synonym for the largest purposeful demolition that the world has ever seen.

Informal planning means informal design, as demonstrated by uncovered electrical and Internet cables strung between buildings in Shenzhen (Photo: Trevor Patt)

While the appropriateness of demolishing lively neighbourhoods is low, it points to more foundational problems within Chinese urban planning practice. In recent meetings with the under-staffed Beijing urban planning department, Al discovered that planners in the city are simply over-burdened amidst national attempts to become 60% urbanised by 2020: “they have to plan for 200,000 housing units every year; the last thing they are looking at right now is rethinking their housing model.” While little can absolve China’s planners from blame, constructing a new city on the outskirts of the city on an annual basis is a monumental challenge.

A glimpse inside housing in Shenzhen’s Dafen Village (Image: Villages in the City, edited by Stefan Al)

The future of urban villages is uncertain at best and doomed at worst, with demolition and decommission being the future for many. It was for this reason that Al and his team of researchers chose to “celebrate the continuity and unpredictability” of the urban village through “performative” research. By using unconventional presentation methods that give insight into the urban texture and the daily lives of the inhabitants and place-makers below the thin line skies, Villages in the City showcases the heights that urban informality can reach.