It all started when the neighbor on my right knocked at my door to borrow the extra mattress I had available. “Thanks girl”, he said. “To be honest, the friends I’m hosting don’t care at all about the quality of the mattress. We’re barely going to sleep this weekend. You are going to ADE too, aren’t you?”

Being sick as hell, I smiled politely and closed my door to this mattress-carrying French guy and went back to bed, where I was planning to spend the night with tea and honey. But one hour later, the neighbor from across the corridor knocked at my door as well. That is when I understood that something was happening. This ADE thing was real, and I would not get away from it so easily.

Is the mass movement embodied by this festival a gift to Amsterdam’s young inhabitants, a global strategy, or is there a general tendency of the city to become exclusionary and ruled by commercial interests?

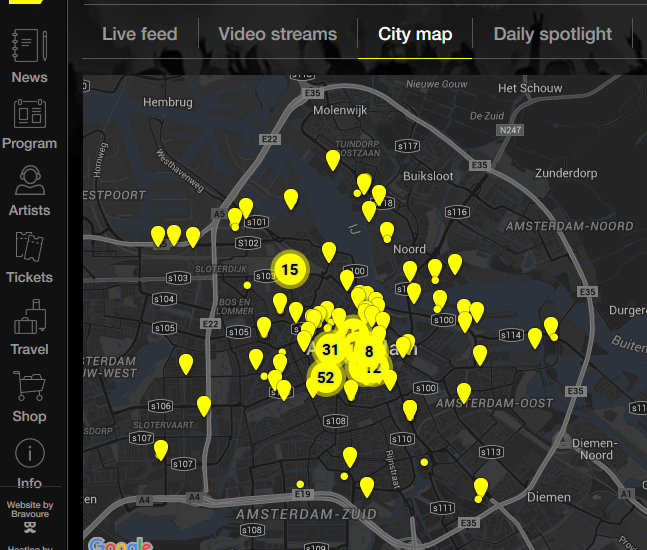

Locations of Amsterdam Dance Event. Source: ADE

A Mass Culture Festival

On its official website, the festival description made clear that not knowing about ADE implied living in a cave like an underdeveloped kind of monkey.

“The ADE Festival features 300 events and 2,000 DJ’s over five days in 80 clubs and venues, which together combine to make Amsterdam one of the busiest and most inspiring clubbing cities in the world.”

Although impressive, these huge numbers are not surprising: electronic dance music is the dominant music genre of the 21st century in western societies, and it has been long since the first dance club opened in the late 1960s in the United States. The genre has gone from underground to mainstream at the speed of the light and has evolved into dozens of recognized subgenres. In Amsterdam in 2015, saying that we are going to go to a club is often equivalent to saying that we are going to listen to electronic dance music. No wonder that the two neighbors who tried to borrow my extra mattress automatically assumed that I, like them, was going to spend my weekend at ADE.

Washing Down the Underground

Amsterdam is the perfect place for such an event to happen. In the 1980s, the city center was a haven for drug addicts and squatters, a place to avoid for its terribly dirty and unsafe streets. But today, the “city of vice” has managed to reverse the tendency while taking advantage of this previous infamous image by making it marketable and desirable. Tourists flock by thousands to a city that is a brand in itself, where they are allowed to feel rebellious by getting tattooed, smoking pot and buying weed-flavored condoms.

Like drugs in Amsterdam, electronic dance music has been washed out of the subversive content it had at its origins before being spread around as a proof of the perfect inclusion of Amsterdam in the Global City network, edgy but not too much. Its electronic music leadership gives to the city a comparative advantage in the global city competition, where every local government struggles to become a cultural-cognitive center that will attract the educated elite. In other words, events like ADE contribute to positioning Amsterdam on the global map, a city where dance music is everywhere, for everyone.

ADEv – The Alternative Festival that Makes Dance Music Political

But while these 350,000 electronic music lovers were booking their tickets to one of the hundred of events of the festival, a slightly different crowd was gathering under the rain to march in the city center for a counter-event named the ADEv.

The acronym stands for “Amsterdam Danst Ergens Voor” (Amsterdam Dances For a Cause), its logo mimics ADE’s and despite the repetitive assertion that “we don’t dance against, but for”, it is obvious that ADEv mocks the ADE and its overcommercialization of music. The ADEv manifests itself through a street parade during which people can dance and celebrate being able to do so without being expelled from the street by the police, for once. It calls for making music accessible to the poor and serves as a window for the small cultural and artistic squats that are struggling to survive in an increasingly gentrifying city.

“We dance for a certain ideal, not for Samsung. We are the only freely accessible, non-commercial ADE event.” said ADEv spokesman in 2014.

A protest where people blast sound in the main streets of the city to call for visibility for the underground culture, which by definition only exists when hidden, might seem very paradoxical. However, this festive event is a reminder that space is not neutral, but political. Even such a massive event as ADE can exclude some categories of people through commodifying many areas in the city, making it a giant window for big corporations during a whole week.

Before rejoicing at the idea that Amsterdam is becoming a hotspot for electronic music fans, it would maybe be relevant to sit down and wonder who is benefitting from this event. My neighbours obviously are, as well as Samsung and the marketing department of the city hall of Amsterdam. But as the underground counterpart of this massive festival makes clear, it is also one more push against non-commercial music and one more sign that the city is oriented to cater the needs of one specific category of the population: the one who can afford a ticket to these often expensive events.

When cycling home that Saturday, I stopped to contemplate the roof of the Amsterdam Arena while it became red and blue and yellow again and imagined those of my friends who had signed for such an impressive experience. They would soon be dancing in rhythm all together with 40,000 strangers and the most famous DJs in the world. As for me, I would be in my bed, with tea and honey.