Hong Kong is a city of connections. It is connected by plane, by bus, by ferry, by taxi, and by mass transit. And, to be fair, Hong Kong performs effectively in that regard. Being one of the world’s megacities, it is successful in bringing people from point A to point B through a generally efficient, if bizarrely organised, public transportation system. 90 per cent of daily travel within the city is done by public transportation. Wherever you are in Asia’s world city, there is always a minibus, bus, MTR train, or taxi waiting for you. You can be in the most remote part of town and there they are, smiling and waiting for you to pay the fare to bring you to civilization again. Great. Well done, Hong Kong.

But it is not enough. No, not enough at all. Hong Kong is planning to build a bridge. A massive one: the Zhuhai-Macau Bridge. You might have heard of it, but we’re willing to bet that you haven’t. It’s time to get acquainted with one of the biggest undergoing infrastructural projects on the planet.

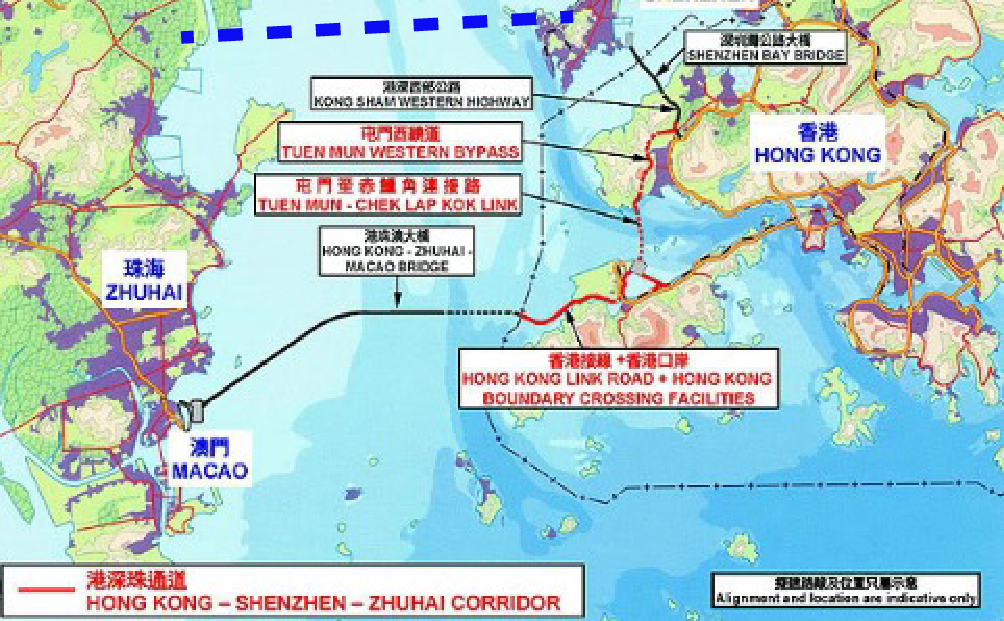

Let’s introduce her. The Zhuhai-Macau Bridge is 29.6 km long, connecting Hong Kong with the metropolitan areas of Macau (full of casino developments) and Zhuhai (full of Chinese bureaucracy). The bridge is scheduled to be completed in 2016. The Hong Kong government is investing 8.4 billion HKD (approximate €840 million) to link up its economy to Mainland China via a land(-over-the-sea) bridge.

That is not all, however. The bridge will make sure that Hong Kong is less dependent on the fastest growing economic region in the world: Shenzhen. Urbanists have waxed poetic about that little town (50.000 inhabitants) that exploded within 30 years’ time into a gigantic metropolis (according to some estimates as much as 15 million), twice the size of its more southern and (mildly) more democratic counterpart. Now, a significant part of Hong Kong’s exports (which in itself is a significant part of its economy) is transferred via the air and sea ports of her bigger, northern sister. The threat of being outrun by Shenzhen in the long run seems to be a solid legitimisation for Hong Kong to start diversifying its portfolio of connectivity. Transit time to the Mainland is cut dramatically, by 80 percent. That is a serious reduction in travel time, to be sure.

But what is the deal here? Is this bridge really going to push Hong Kong’s economy forward? Is it really going to significantly benefit the airport, the seaport, the financial sector, the tourism industry, and, eventually, the people that actually live in Hong Kong after all of it has trickled down? Are the beliefs of the current administration leading Hong Kong’s government grounded in reality, or are the positive estimates overly exaggerated in the way that Flyvbjerg (‘Megaprojects and Risk’, 2003) suggests is plaguing contemporary megaprojects in megacities?

No. The idea that Hong Kong will benefit from such a project is farcical.

In terms of transportation, the project seems to be mildly beneficial. When compared to the ferry, travel time to is reduced by 25%. With the bridge, it will take a mere 45 minutes to travel from Hong Kong to Macau. Currently, one would generally take the ferry, which takes about one hour. If you’re brave enough to drive to Zhuhai from Hong Kong, the journey takes you via Guangzhou in the north to go down south again along the opposite side of the Pearl River Delta. Travel time? 2 hours, 30 minutes. Okay, that seems reasonable as it is, doesn’t it?

But the integrative economic benefits claimed by the HKSAR government seem to be little more than exaggeration piled upon exaggeration. As one can see in the cringe-worthy YouTube videos posted by AWTC (Lo & Lam) Consultancies, the belief is that the bridge will connect Hong Kong to not only the western section of the Pearl River Delta, but will connect it to the faraway Yangtze Delta and even the whole of Southeast Asia. That’s right: the government of Hong Kong is under the delusion that the city will be better connected to Singapore and Indonesia by building a bridge that ultimately ends northward.

What is the target user group for such a major piece of infrastructure? A diminutive 5 percent of the Hong Kong’s population actually owns a car, largely because it is successfully restrained by the extreme costs of ownership and operation in Hong Kong. That is one of the planning measures that is generally viewed as one of Hong Kong’s major successes. And, apart from that, is Hong Kong actually concerned with decreasing air pollution and enhancing sustainable urban and rural development? What will happen to the city’s already-poor air quality when the Zhuhai-Macau Bridge is built and ultimately in operation?

Many critical questions remain, unanswered. Or you may answer them yourself. This bridge will come and it will be shown to the world. Dramatically.

One closing thought. See the dashed line on the map (the clear blue one)? That’s a second bridge, linking up the eastern side of the Pearl River Delta to the western part. By whom it is built you ask? By Hong Kong’s bigger sister, Shenzhen.

Good luck, Hong Kong. Keep on connecting.