Singapore is an intriguing case to witness successful urbanization combined with rapid economic development: it is one of the most successful top-down planned societies. The smallest city-state of Southeast Asia made an unbelievable transition from a poor, isolated, and agricultural society towards one of the wealthiest cities in the world in merely five decades. However, this transition came at environmental costs, and now Singapore is plagued by environmental issues like flash floods, urban heat, a lack of fresh drink water, and high international energy dependency. This is no surprise since more than 5.5 million Singaporeans live on merely 700 square kilometres.

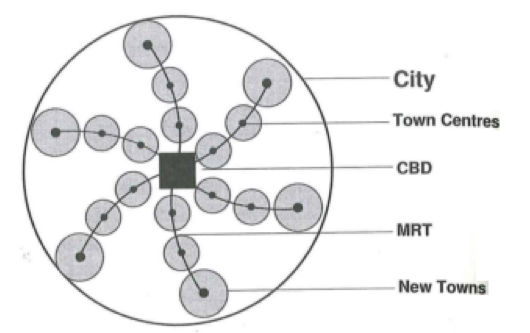

City Concept Applied to Singapore (Source: Liu Thai Ker)

In Singapore’s top-down tradition, most environmental issues were initially approached rigidly, but changing conditions made some of these measures ineffective on the long run. In this contribution, I highlight some of Singapore’s new innovative approaches towards environmental issues that threaten the small city-state based on a study trip in January 2013 and a small explorative research project I conducted together with two fellow students.

Environmental Issues and Innovative Responses

Although Singapore has successfully tackled some large environmental issues such as car usage and water threads, it seems that the early “plan and provide” model is not always adequate anymore because environmental hazards intensify and the society is changing. I briefly asses new approaches in transport planning and Singapore’s water drainage system to illustrate how Singapore is reinventing their approach to environmental issues.

Sustainable Transport

Already starting in the 1970s, the car became a problematic means of transportation due to congestion and decreasing of local air quality. As a result, the government felt obliged to act, and after already developing a comprehensive transit system in the 1980s, they increased their effort with the 1991 concept plan where urban development was planned in high capacity transit corridors (Yang & Lew have reviewed Singapore’s transit orientated development plan in greater detail). However, the metro lines are mainly focused on the central district, and for example for visiting a relative in another new town development, one has to change trains or go by bus. The city is approaching this problem by constructing tangential metro lines, but has not considered the bike as an alternative to increase accessibility.

A Platform on Singapore’s MRT Rapid Transit System (Source: Jason D’Great)

First opposing the government, a group of local cycling advocates introduced the bicycle as a new lifestyle based transportation method. There are now multiple bicycle organizations active that support and stimulate bicycle use and organize events such as the Singapore Cycling Federation. As a result, riding a bicycle became a transport niche in Singapore, but increasing ridership led to safety problems which led to new traffic regulations, with one example being the “1,5 meter norm” when passing a cyclist with your car.

However, after some time, the transport department embraced the bike as a serious solution to increase the flexibility of transportation. Now, seven new towns are designated as cycling towns, the Park Connector Network is being developed to connect green areas with bicycle routes and footpaths, and sidewalks are being widened to accommodate safe biking areas (walking and cycling measures in Singapore are discussed more specifically by Koh, Wong, Chandrasekar, and Ho [PDF]).

As a result, innovative planning measures focused on increasing the bike-share give Singaporeans the option to safely bike to destinations close by. What began as a bottom up biking movement has now become a serious sustainable transit alternative, increasing the transport resilience of Singapore.

Water Drainage

Heavy rainfall is common in many Southeast Asian countries, and, in urbanizing Singapore, an extensive drainage system to cope with excess rainfall has been developed. It is impossible to miss: a complex concrete jungle of waterways, channeled rivers, and reservoirs that you stumble upon everywhere in Singapore.

Concrete Drainage System in Singapore (Photo: Maarten Markus)

However, the drainage system has troubles with increasing climate change induced rainfall. Furthermore, urban development has unexpected local effects on the drainage capacity. When a building is built on a plot that used to be green, the absorption power of the same plot decreases heavily because concrete buildings do not hold the rain. As a result, the well-structured drainage system does not cope well with increasing urban development, and the governmental organization responsible for the drainage system, the Public Utilities Board (PUB), is looking for new ways to tackle the increasing localized flash floods that paralyze parts of the city.

New approaches are found in combination with an effort to green the city. Buildings are now obliged to integrate green surfaces to compensate for lost green areas. Interestingly, the developers are free to experiment with new solutions, leading to a diversity of innovative concepts that integrate urban vegetation differently. Another result of this ‘greening Singapore’ policy is the mitigation of the urban heat island effect, a problem felt by Singaporeans for many decades which is now dealt with as well. The PUB is also working together with the national park authority, NParks, to use existing parks as buffers to accommodate excess rainfall. As a result, the drainage system is becoming integrated with Singapore’s beautiful parks, leading to more blue recreational spaces and accessible waterways, instead of concrete channels.

A Fresh Approach to Accommodating Excess Water (Photo: Maarten Markus)

In sum, the new approach effectively makes use of the innovative capacity of the real estate development industry, and knowledge on urban greenery which was always there but not integrated in the PUB.

Experimental Development Strategies

Singapore is often referred to as an urban success story. Developing a strong, global competitive knowledge based economy without abundant resources seems almost impossible, especially in the time frame of about five decades. This accomplishment would not have been possible without a state government strongly oriented towards urban development policy. However, rigid planning measures can prove ineffective when new, unexpected problems arise.

In the examples mentioned, the Singaporean government appears to have successfully changed their approach: from rigid top-down planning towards more flexible, locally-based planning interventions. Singapore is a great example of uncertainty in planning. In order to tackle the unforeseen, one has to base its planning practices on the fact that there is such a thing as uncertainty. Singapore shows that even within a top-down planning tradition this can be done, however, an important condition is that the existing practices are directly challenged. Singapore became more environmentally sustainable because of the implementation of innovative planning solutions, but without the necessity to do so, these experiments would have never been approved.

This article written during a research apprenticeship at the Urban Planning Group at the University of Amsterdam. The author would like to thank Stefan Klingens and Saskia van Groeningen for their part in the research project in Singapore.