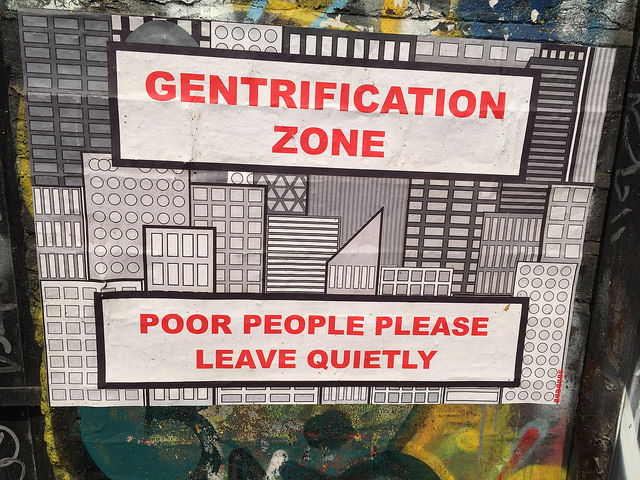

Due to continuing globalization, many cities across the globe are becoming increasingly inter-exchangeable in terms of architecture, facilities, employment and fashion. Particularly the similarities between the world’s main financial centres can quite easily be recognized by their eye-catching skyscrapers designed by renowned starchitects, which often accommodate offices of the world’s leading advanced producer services companies such as Deloitte, HSBC, JP Morgan or Baker & Mackenzie. In the near vicinity of those, it is quite likely that one will find at least a Starbucks, a McDonald’s, a Subway and a Dunkin’ Donuts, while in the adjacent gentrified areas, it is most-probably not too difficult to comfort yourself with a very familiar soy latte, that a skillful barista with fashionable glasses and a well-maintained beard serves to you alongside your favourite vegan cheesecake. On the seam side of such developments, however, there may be a hidden class of low-end service workers, often migrants, that find themselves in increasingly precarious situations as a result of ‘universal’ and ‘mobile’ neoliberal social security, housing and labour policies.

Although these trends and images might indeed to some more or lesser extent apply to most of the widely-known world or global cities, there are still a lot of cities across the globe that have a large amount of inhabitants, but which do not quite correspond to such supposedly ‘global’ developments. These cities are generally considered to be relatively ‘off the map’ when it comes to theory or knowledge production within the academic field of urban studies. For that reason, there have been voices within the academic field of urban studies lately which argue that urban theories should actually be less focused on universalizing assumptions. Instead of comparing cities by looking at their global economic connectivity or the extent to which local policies can be characterized by neoliberalism, they argue, we should instead focus on more particular, bottom-up empirical observations, preferably from locally embedded researchers, in order to nuance some of the frequently taken-for-granted political-economic presumptions that may come along with contemporary theories regarding globalization and its impact on the universal urban.

Debates and disputes

The alternative ontological, epistemological and methodological approaches that have been suggested by this very group of self-identifying ‘post-colonial’ urban researchers have led to some fierce academic debates. In 2014, economic geographer Jamie Peck wrote an article in Regional Studies named ‘Cities beyond compare?’, in which he openly reflects upon the question whether and how comparisons between cities, particularly between those located in the Global North’ and ‘Global South’ respectively are still valid. Although he does acknowledge that some of the criticisms on essentialist ‘top-down’ urban theories are valid, he simultaneously advocates the ever-lasting importance of theory, and therefore expresses his concerns on the fact that urban comparisons nowadays tend to become more and more horizontal, focusing on difference-finding and stressing the ‘unique’ and ‘exceptional’ elements that each city possesses. According to Peck, we should thus be careful not to entirely abandon the existing structural political-economic insights by shifting towards new, and supposedly more complex geographies of urban (anti-)theory. Urban comparisons, in his view, can still be very useful in order to critically assess the applicability of existing theories in different contexts, and to subsequently adjust rather than radically reject them.

The diversity of comparisons

A current look at the state of the art literature proves that cities are not at all beyond compare. Notwithstanding one’s ontological persuasion or preference, it seems to be widely acknowledged at this point that comparative urbanism can be revealing in multiple regards. While some urban scholars, in line with Peck’s approach, thus tend to depart from more abstract and universal structural theories, primarily aiming to find convergence, others believe it is more revealing to highlight variations, or to focus on individual human experiences or imaginaries while conducting urban comparisons instead. A number of scholars nowadays furthermore stress the relevance of looking at inter-connections between cities, and how that offers fruitful lenses through which comparative urban studies can contribute to our understanding of the urban processes across the world. Even when comparing two cities that appear to be very random in terms of their mutual relations, there are nearly always some similarities to be found. Hanoi and Ouagadougou for instance, two cities that are miles apart from one another and have a fairly different physical appearance, share that they are both former French colonies, as well as that they have both witnessed revolutionary socialist regimes and subsequent large-scale privatizations of land ownership. Cities can be even be compared trans-historically: as Jan Nijman illustrated, Miami’s recent history actually has some deep analogies with 16th century Amsterdam (in terms of being open and multi-cultural), 19th century Shanghai (in terms of illegal development and drug money), mid-20th century Hong Kong (in terms of being a destination for ideological refugees) and with Dublin in terms of both being central regional economic nodes in the shadow of the world cities of New York and London respectively.

The Proto City-UGent series on comparative urbanism

During first semester of the 2018/2019 academic year, the students that took the master’s course Urbanization in Global Perspective at Ghent University (Belgium) were required to work on two assignments that both related to the aforementioned debates on the broader limitations and opportunities of comparative urban studies. For their second assignment, their challenge was to ‘compare the (seemingly) incomparable’. The students were all (randomly) appointed to two cities, one of which located in the Global North and one in the Global South. Apart from briefly discussing both cities’ path-dependency, they had to reveal to what extent a number of issues that were discussed during the course’s lectures (i.e. ‘spectacular urbanization’, ‘polarization and socio-spatial inequality’ and ‘global connectivity’) are occurring in both cities, how certain similarities or differences between them can possibly be understood and whether they could find any ‘relational inter-connections’ between the two.

In the coming weeks, the Proto City will publish a selection of (reduced and adjusted versions of) these students’ papers. Eventually, they were allowed to re-write their work and decide by themselves which specific issue(s) they wanted to emphasize in terms of their comparisons, or if they wanted to keep their comparison rather broad on purpose. In any case, many similarities as well as differences will be highlighted, between San Francisco and Dar es Salaam, Rome and Rio de Janeiro, Edinburgh and Kuala Lumpur, Sydney and Lima and Amsterdam and Tehran.

One of the central questions that remains, is how we can actually define ‘the global’ in relation to the concept of the ‘urban’? What makes urban processes global, rather than national or regional, and how do certain things ‘circulate’ ‘globally’ whereas other do not? And can comparative studies contribute to opening up current ‘black spots’? We invite all of you to engage in this debate following our upcoming series, and look forward to hear your thoughts and impressions!

NB: The featured image on top of this article is taken in Vancouver by Tim Gouw (Unsplash)