Isabella Rossen investigated the rapid process of neighborhood change initiated by the construction of a new metro station in Kennedy Town, Hong Kong. This photo report illustrates how transformation of built form, retail landscape and social fabric has been set into motion since Kennedy Town is connected to the city’s metro network.

Large-scale projects such as the establishment of a new metro connection to a neighborhood have the potential to cause a rapid transformation of the surrounding area. The implications of a new metro station for the socio-economic character and local identity of a neighborhood vary across cultural and institutional contexts.

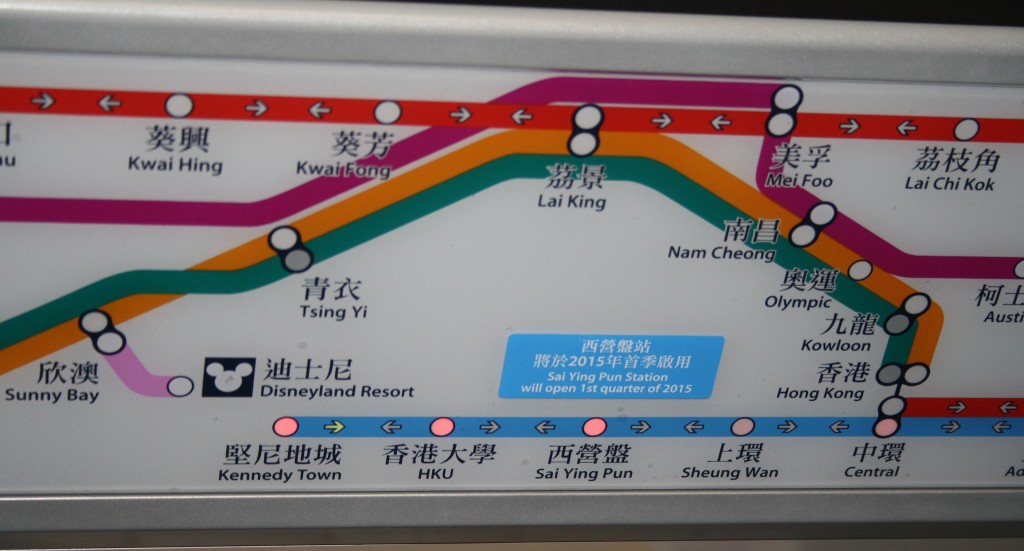

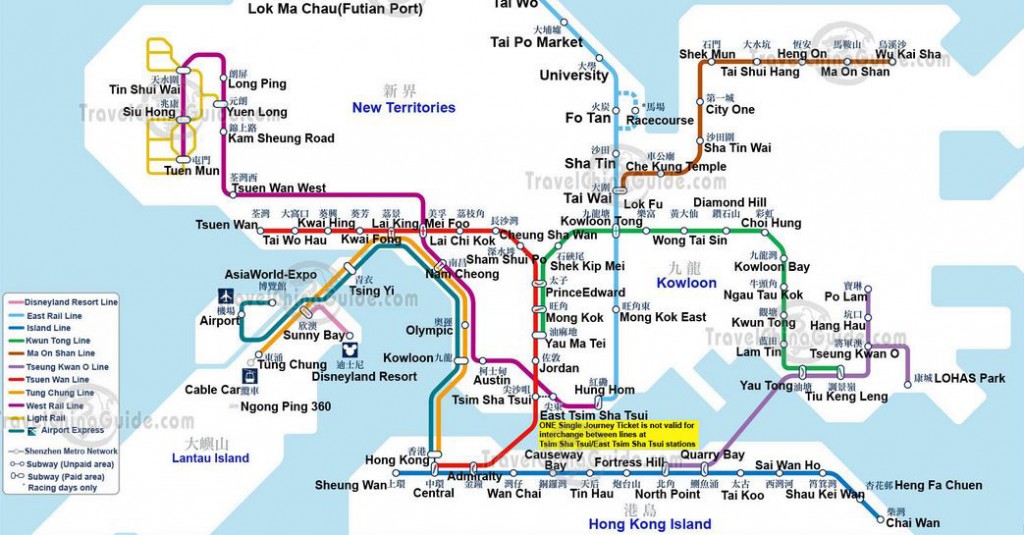

Having researched the process of change triggered by the opening of a new metro station in the neighborhood Kennedy Town in Hong Kong, this essay illustrates the transformations in the streetscape of an old and traditionally working class neighborhood. A closer look at Catchick Street, one of the main commercial streets in Kennedy Town, shows how the West Island Line extension of Hong Kong’s Mass Transit Rail (MTR) sets into motion different dimensions of change.

A New Metro Station in Kennedy Town, Hong Kong

After four years of construction works, Kennedy Town’s new metro station opened in December 2014. The metro connection to Kennedy Town, the most Western part of the Northern side of Hong Kong island, is part of a larger-scale extension of Hong Kong’s West Island metro line, a project that was officially announced five years ago.

The tram, formerly important mode of transportation for Kennedy Town and characteristic part of the streetscape of Catchick Street (Photo: Isabella Rossen)

Until the recent metro station went into operation, Kennedy Town was a rather quiet and remote borough due to the absence of a fast connection to Central Hong Kong. The most important modes of transportation connecting Kennedy Town with Central Hong Kong were the tram and a myriad of bus routes.

A map of Hong Kong’s metro network, before the West-Island line extension (Image: China Travel Guide)

Apart from enabling a rapid commute to the centre of Hong Kong and vice versa, providing visitors an easy access to Kennedy Town, the new metro connection brings about an intricate set of changes in the retail landscape, built form, and social fabric of ‘K-town’, as the neighborhood is increasingly dubbed.

Industrial Functions and Small Businesses

Kennedy Town is one of Hong Kong’s oldest neighborhoods, and used to house mainly industrial functions such as car-repair shops, factories and warehouses. The population was largely working class, from Chinese origin, and there was a relatively large elderly population, also due to the presence of several elderly homes.

The industrial past of Kennedy Town is still visible in the neighborhood’s side streets. Several car repair workshops have remained, however most industrial functions and small-scale local businesses are being replaced by more profitable retail spaces. A young expat resident narrates how he has observed changes in the streetscape of Kennedy Town the past five years:

“There used to be collections of people who would gather along the Kennedy Town Praya, there were series of mahjong tables set up next to the auto repair shops. Those have all disappeared.”

Although a car repair workshop does not seem a very favorable asset to the street life of a neighborhood, social activities such as mahjong are connected to these spaces and the possibility they offer for interaction with the street. Numerous people in the neighborhood point out that what tended to be social spaces for local Chinese residents are being replaced by commercial spaces for newcomers to the neighborhood, such as expats and young professionals.

One of the few remaining old congee shops in Kennedy Town. Congee is a local-style porridge made of rice. A middle-aged resident recalls how his mum or grandmother would take him there “because as Chinese, you know when you are sick you don’t eat rice, you eat congee” (Photo: Isabella Rossen)

Retail spaces in this area catered towards the predominantly traditional Chinese and working-class population. As a resident describes:

“There were many shops selling those local foods such as noodles, porridge, dim sum, and snacks, which are really the kind of things we got as kids. So it’s really the traditional character, which we have in the old district.”

To Hung Kee Furniture Store and its 80-year old owner, Mr To. The so-called ‘mountain goods store’ has been located at Catchick Street since 1945, when Mr. To’s father started this business in Kennedy Town (Photo: Isabella Rossen)

To Hung Kee Furniture Store and its 80-year old owner, Mr To. The so-called ‘mountain goods store’ has been located at Catchick Street since 1945, when Mr. To’s father started this business in Kennedy Town (Photo: Isabella Rossen)

Whilst Catchick Street used to house a variety of Chinese shops, the past few years there are an increasing amount of shops, which many Kennedy Town locals refer to as “new shops with more Western influence.”

One middle-aged resident and social worker describes himself as “too traditional” for the new bars and pubs in Kennedy Town:

“It’s quite strange for the old residents, many bars and Western restaurants we see today. I mean, these are quite trendy, but they don’t have the old flavor and not quite represent the district’s history.”

A high-end liquor store that has opened up shop in Catchick Street a year ago (Photo: Isabella Rossen)

Specialty coffee bar The CoffTea Shop serves high-quality coffee. The owner, Herbert Lau, opened his shop in Kennedy Town in August 2014. He actually chose for this location in Kennedy Town because the “neighborhood feel” appeals to him, and he hopes that the metro connection will not damage the quiet and friendly character of Kennedy Town (Photo: Isabella Rossen)

High-Rise Disruptions

An old Hong Kong style tenement building of 7 to 8 storeys, buildings which are also referred to as Tong Lau (Photo: Isabella Rossen)

There is a close relationship and interaction between built form, economic functions and social activities in the neighborhood. Adrian Cheng, a young resident of Kennedy Town, explains how the Tong Lau plays a special role in the urban fabric of Hong Kong:

“I love those Tong Laus because the Tong Lau has got some old shops downstairs and if those Tong Laus disappear, that means the old shops are gone as well. In many cases those shopkeepers also live upstairs in the Tong Lau. So all their activities are within that building… it has a close interaction.”

Over the past few years, many old tenement buildings have been demolished, and replaced by high-rise flats, often in the form of podium towers that contain luxury apartments. These podium towers are also referred to as “birthday cake buildings” by locals. The nickname birthday cake building comes from the similarity of the tall and thin skyscrapers with elevated podium levels to a birthday cake with different layers and candles on top. The podium, a level elevated some ten floors above the actual ground, contains amenities such as car parks, gyms, swimming pools and shopping malls.

The increase in podium tower high-rise flats has negative implications for the street life and social interaction within the neighborhood. Architectural historian Cole Roskam explains the consequences of an increase of high-rises for the streetscape:

“With high-rises the street life tends to be interiorized, because those high-rises tend to be podium towers. There’s an interest for the developer in maximizing the ground level footprint, and trying to put shops inside of the building rather than having them face outwards.”

This building type thus hinders a connection between the building and the street level. People have to actually enter the building and go to the podium level in order to do their shopping. This excludes an interaction between people on the street and economic functions and amenities which are indoors and do not have a shop front facing the public space of the street.

Many high-rises are being constructed in a very short time-span in Kennedy Town, as the value of land is rising rapidly and developers seek to maximize profit. At least twenty old buildings have been demolished over the past five years. Community worker Edmond Wong Chi Hung of the local community centre has organized meetings with residents to assist them in their communication with the owners or the redevelopers of the premises. He laments that, “in the last five years we have organized these kind of meetings for more than twenty buildings. More than twenty.”

As the old tenement buildings often house both residents on the upper levels and small-scale businesses on the ground floor, their demolition affects the whole economic and social structure of the community. Winnie Tse from CACHe, the Conservancy Association Centre for Heritage, thinks that “the very high-rise buildings, with a clubhouse in the podium, make the residents very detached from the others.” The vertical development in Kennedy Town, and also in Hong Kong in general, thus discourages social bonding.

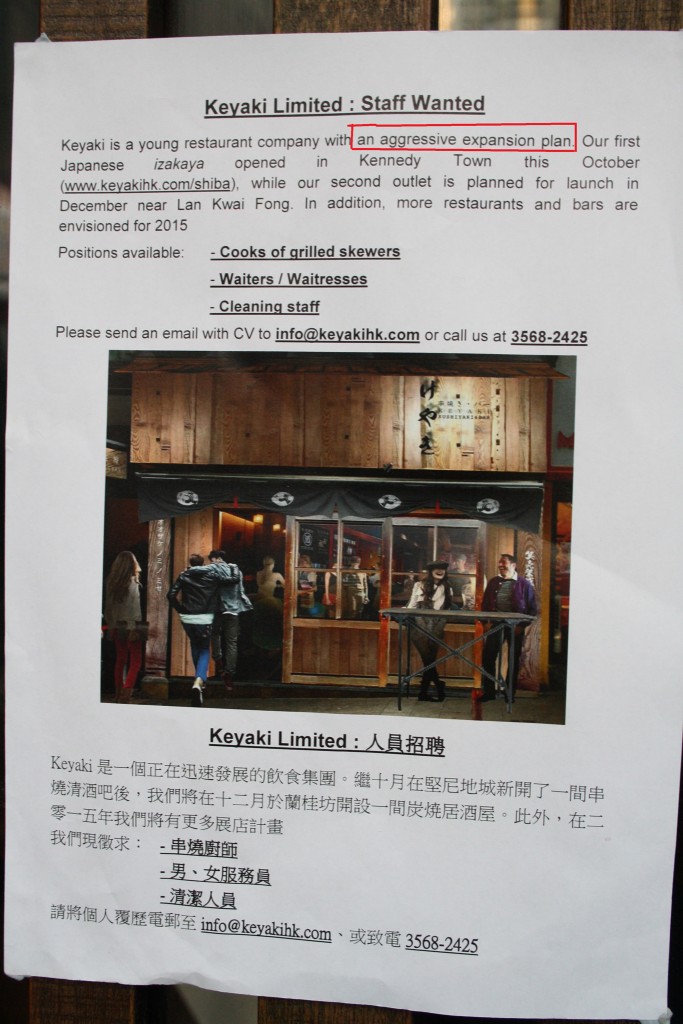

In the space where there used to be an oyster sauce factory years ago, there is now a new Japanese resturant. According to this call for staff posted on the door of the restaurant, they are “a young restaurant company with an aggressive expansion plan” (Photo: Isabella Rossen)

There is currently an influx of up-scale restaurants and bars with a “more Western influence” as one resident describes their character. These retail spaces cater not so much to the Chinese locals, as to a more wealthy group of consumers, often expats or young Chinese professionals aspiring a Westernized lifestyle.

One of the remaining Tong Lau tenement buildings, with a pub in the retail space below (Photo: Isabella Rossen)

Streetscapes on the Move

The insertion of a new metro connection into Kennedy Town brings about more change than merely a shortened commute to central Hong Kong, an influx of visitors and a busier streetlife. The rapid increase of the value of land has led to soaring rents, the demolition of old buildings and the construction of numerous high-rise podium towers to replace them. The changes in the streetscape and retail landscape of Catchick street and the surrounding area point towards a large-scale transformation of the neighborhood and community inhabiting it. Built form, economic functions and social fabric are intricately connected and thus Kennedy Town’s new metro station does not only facilitate movement to and from the neighborhood, but also sets a whole streetscape in motion.

Further comparative research will look into what kind of transformation the Noord/Zuidlijn in Amsterdam is anticipated to bring about in the neighborhood of De Pijp. Will these changes show similarities to the process of urban renewal in Kennedy Town? Or is a different impact plausible in the urban context of Amsterdam’s de Pijp?