Sweden was internationally recognised as a picture perfect egalitarian country. The well-mediatised riots in Järva shattered this falsified image. What is scantily mediatised are the preceding protests. Whilst those protesting prior to the riots cannot and should not be assumed to be the same as the rioters, it does indicate political unrest in the suburb and experiences of grievances, begging the question: what is happening in the periphery of Stockholm?

Järva could be considered a peripheral neighbourhood with a high concentration of socio-economic disadvantage. Scholars such sa Ålund and Schierup (1991; 2009; 2014) highlight are created through a racialized labour market, institutional discrimination, and police repression. The periphery has seen a recent surge of crime and the tragic death of 23 young people in the past two years. The rising insecurity has led to a new protest movement in the suburb, translated as the Suburb against Violence.

Protest in Rinkeby on the increasing insecurity of the neighbourhood as ‘symptom of poverty’ Source – https://www.facebook.com/forortenmotvald/

For Järva and many other peripheral neighbourhoods, the prevalent urban policy is a tactic of deconcentrating poverty, guided by the belief that it will reduce negative effects for residents and solve the problematic issue of the periphery for planners as a manageability problem (Andersson & Musterd, 2005). The policy intervention is usually an introduction of different housing tenures to solve the manageability problem associated with modernistic post – war arhcitecture, often found in the periphery. Whilst those in these areas are more dependent on policy interventions due to their disadvantaged position, the social mix policy has been criticised for its limited and often negative results of displacement (Galster, 2007; Bridge, Butler, Lees 2012)

Moreover, in the context of urban growth, the social mix policy privileges the middle class’s right to space in what can be considered to be “state-led gentrification” (van Gent, 2013). Such an approach was adopted in Järva, and some residents identified the disjuncture of planning for a future, middle class population and a group of residents effectively mobilised against the plans in 2007 thus shedding light on a routinely muted planning contradiction.

Despite the retraction, the fate of Järva remains unknown. The pursuit of a social mix policy are at the crux of the current tension of urban planning between intraurban inequalities and urban growth. Whilst cities are competing in the global urban rat race to stay relevant in the fast-paced creative economy their urban form experiences increased stress due to high demand. Peripheral neighbourhoods are becoming the ideal strategic locations to accommodate urban growth with cheaper land, transport links and proximity to the centre (Salet & Savini, 2015). However are vulnerable due to low economic and social status and the social mix policy works to invisibilize poverty, potentially worsening the situation.

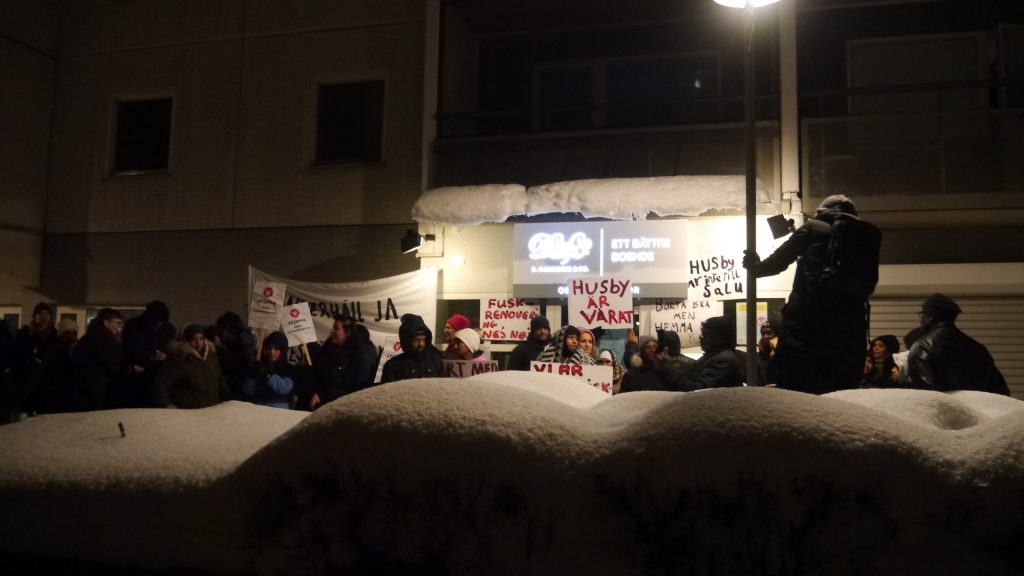

Protest in Husby on poor housing conditions. Source – author

In the case of Stockholm this is exacerbated due to rapid adoption of neoliberal ideology. The previous “Swedish model” responsible for the countries polished national identity has been considerably dismantled: housing once the pillar of the system has been the main alteration. The previous housing policy was based on tenure neutrality and in 1960s resulted in the building of neighbourhoods such as Rinkeby and Husby based on values of universalism and affordability for all. In 2017 the country advocates home ownership with tax breaks and subsidies for homeowners, whilst social housing subsidies have been removed. Meanwhile, housing associations have changed function and now perform as a private company, diminishing the amount of social housing. In Husby along with other suburban neighbourhoods, residents have protested against the deteriorating conditions and the increase in price after renovations, particularly acute in a time of rising inequalities.

Whilst the issues in Järva remained unanswered to, the municipality has published a vision for Stockholm – “Stockholm for Everyone”. The vision functions as a strategic framework in decision making processes on spatial interventions. Asking planners to ask themselves is this a Stockholm for everyone? However, who is everyone? The city is divided by a heterogeneous population with stark inequalities, and whilst the vision makes it clear that it aims to be recognised worldwide for its innovation and creativity, it fails to address how the challenge of a divided city can be resolved. Residents are placing their voices forward, presenting their demands and shouting for their right to the city. The question of what the municipality will do with this and the subsequent response from residents remains to be seen.